The Case for Specialized Business Courts in Texas

Introduction

Business Courts in the United States

Definition of and Commonalities in Business Courts

A History of Business Court Creation in the State

Delaware Leads the Way

Other States Follow Delaware’s Lead

States’ Failed Attempts to Implement Business Courts

Case Eligibility Requirements

Procedural Access Into (and Out of) Business Courts

Selecting and Training the Judges

Publishing Court Opinions

Efforts in Texas to Adopt Business Courts

Does Texas Need Business Courts?

Evolving, Complex Business Practices and Texas’s Economy

Judicial Efficiency and Precedential Consistency

Critics of Establishing Business Courts

Relationship of Business Courts to Other Procedures

Jury Trials

Alternative Dispute Resolution

Concluding Remarks

Introduction

There have been repeated legislative efforts in recent years to create specialized business courts in Texas. In 2007, TLR Foundation published The Texas Judicial System, Recommendations for Reform, outlining numerous suggestions for changing the structure and operation of Texas’s judicial system, including the creation of complex litigation courts—a concept similar to business courts. 1 Unfortunately, the bill seeking to implement TLR Foundation’s proposal for a complex litigation court failed in the closing days of the 2007 legislative session.2 Since 2007, most legislative sessions in Texas have seen a bill introduced to create some form of business court system in Texas. So far, none of these efforts have succeeded, either.

This paper discusses the value and purpose of business courts, which states in the U.S. have adopted them, the common aspects and history of these courts, prior legislative efforts to establish business courts in Texas, arguments for and against the creation of business courts, and ideas about why these courts should be created in Texas.

Business Courts in the United States

Definition of and Commonalities in Business Courts

Generally speaking, business courts are state tribunals dedicated to handling business disputes or complex litigation within that state’s jurisdiction. Although state-by-state variations make it difficult to formulate a universal definition, one commentator has defined “business court” as:

Another commentator has divided these specialized courts into three groups, based upon their eligibility requirements:

1. “pure business courts,” where the parties must be commercial entities, but the dispute need not be complex;

2. “complex business courts,” where the parties must be commercial entities and the case must be complex; and

3. “complex civil courts,” where the parties need not be businesses, but the cases must be complex.5

Generally speaking, business courts are state tribunals dedicated to handling business disputes or complex litigation within that state’s jurisdiction. Although state-by-state variations make it difficult to formulate a universal definition, one commentator has defined “business court” as:

- a specialized docket, most often involving disputes either between two businesses or between various factions within a single business organization;

- designated judges who consistently hear such business disputes, thereby expanding their expertise regarding both business law concepts and management of complex litigation;

- special training for the judges assigned to such courts;

- Often a minimum jurisdictional amount;

- assignment of a single judge to handle each dispute from beginning to end, so as to eliminate the burden of having to familiarize numerous judges with often-complex facts;

- aggressive case management by the assigned judge, intended to reduce the amount of time needed to resolve disputes; and

- issuance of a published, written opinion by the assigned judge, for the purpose of building up business law precedent within the state.

A History of Business Court Creation in the States

Delaware Leads the Way

The grandfather of business courts in the U.S. is Delaware’s Court of Chancery, which was created in 1792. Strictly speaking, a “court of chancery” is a court that deals in principles of equity, not in questions of law. Over the decades, Delaware has actively and successfully courted large corporations to charter in its state, and its Court of Chancery has come to represent the “gold standard” in resolving commercial disputes for these corporations, as well as a court known for formulating influential business law precedent.6

The court adjudicates a wide variety of cases that mostly include corporate matters, trusts, estates, and other fiduciary matters, commercial and contractual matters in general, questions of title to real estate, and disputes involving the purchase and sale of land.11 Because the Court of Chancery is a non-jury trial court, when issues of fact to be heard by a jury arise, the court may order such facts to a trial by the Delaware Superior Court. 12

The court boasts that it “is widely recognized as the nation’s preeminent forum for the determination of disputes involving the internal affairs of the thousands upon thousands of Delaware corporations and other business entities through which a vast amount of the world’s commercial affairs is conducted” and that “[i]ts unique competence in and exposure to issues of business law are unmatched.”13

What makes Delaware’s Court of Chancery laudable is its ability to efficiently adjudicate complex and sophisticated commercial disputes, a result from over 200 years of existence and experience. Lee Applebaum, a leading attorney, writer, and advisor in the business court sector, described Delaware’s success:

As opposed to the courts and dockets for [other U.S.] states—which were specifically created to specialize in handling business and commercial disputes— the Court of Chancery grew organically into that role over the course of 225 years. This specialization was a logical outgrowth given that the court’s historical subject- Page 5 of 25 matter jurisdiction over equitable claims frequently resulted in it hearing claims seeking injunctive relief (such as claims seeking to enjoin mergers) or claims challenging the conduct of fiduciaries.14

Another valuable characteristic of the Chancery Court is that it publishes its opinions, which are made available online. 15 By making these court decisions available through a searchable database, attorneys and businesses are able to navigate the extensive commercial case law in Delaware.

The Court of Chancery’s prestige is based on its legal precedence relating to corporate cases (i.e., disputes in equity between members, officers, directors, or shareholders of a particular company).16 The court rarely hears lawsuits for money damages arising from other types of business disputes—which is why the Superior Court was created. 17

Delaware’s Superior Court is a court of law that has heard plenty of complex business law disputes over the years, too. 18 The Superior Court’s Complex Commercial Litigation Division (CCLD) was established in 2010 and hears any case that:

- includes a claim asserted by any party (either directly or as a declaratory judgment action) with an amount in controversy of $1 million or more;

- involves an exclusive choice-of-court agreement or a judgment resulting from an exclusive

- choice-of-court agreement; or

- is designated as complex by the president judge of the court.19

Cases excluded from the CCLD include:

- any case containing a claim for personal, physical, or mental injury;

- mortgage foreclosure actions;

- mechanics’ lien actions;

- condemnation proceedings; and

- any case involving an exclusive choice-of-court agreement where a party to the agreement is an individual acting primarily for personal, family, or household purposes or where the agreement relates to an individual or collective contract of employment.20

In the CCLD, complex business disputes are handled similarly to Chancery Court matters in they are assigned to a single, specialized judge from start to finish and may be submitted to a jury.21 A party who opposes CCLD identification may do so by a motion filed prior to the mandatory scheduling conference or at such other time directed by the assigned judge.22 If the assigned judge determines that the case is not a qualifying case, the case is reassigned to a court official. 23

Other States Follow Delaware’s Lead

The recent movement toward establishing business courts in other states began around 1993, with initial experiments in Manhattan and Chicago.24 No two states have adopted identical systems and, at present, no uniform national model has been developed for business courts. Precisely because of the myriad forms of business courts that states have instituted, there are numerous synonyms (and near-synonyms) for these courts, including specialty courts, chancery courts, complex litigation courts, commercial courts, high-technology courts, and cyber courts.

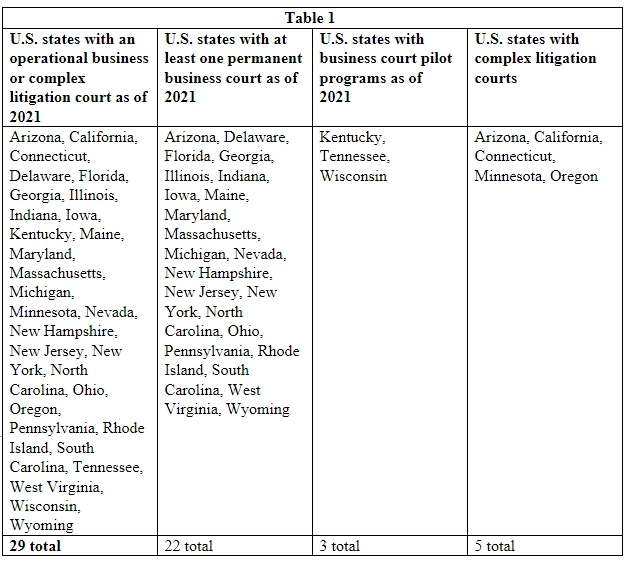

As of the publication of this paper, twenty-two states have some form of permanent business court, and three states (Kentucky, Tennessee, and Wisconsin) have pilot programs currently operating. 25 The following states (listed in order of adoption) have at least one business court that is permanently operational as of 2021:

New York, Illinois, New Jersey, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Nevada, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Maryland, Florida, Georgia, Maine, South Carolina, New Hampshire, Delaware, West Virginia, Michigan, Iowa, Arizona, Indiana, Ohio, and Wyoming.26

Additionally, at least five states—Arizona,27 California, Connecticut, Minnesota, and Oregon— have established complex litigation courts that are either in addition to an already-established business court or are similar to a business court in structure and function but handle a broader range of cases, including non-business matters like mass tort and environmental cases.28

States’ Failed Attempts to Implement Business Courts

Although general historical trends have favored creating business courts (or a similar tribunal), its advance has not been uniformly successful. Colorado, for example, extensively studied the issue and piloted a business court in 2000 but ultimately did not institute the court. 29 Similarly, Alabama’s Commercial Litigation Docket ended its activities in 2015 for possible constitutional issues.30 As discussed below, multiple attempts have been made in Texas to create business courts, all of which have failed.

Many states have established programs on a provisional, city-by-city basis (rather than uniformly doing so statewide).31 This has sometimes resulted in failure in particular localities due to inadequate funding, poor organization, or political pushback, even as other business courts within that same state thrive.32

Case Eligibility Requirements

For a case to be qualified for a business or complex litigation court, there are typically two main considerations: the type of dispute and the amount of damages.

In states that base eligibility for accessing a business court on the amount in controversy. the amount required can be as low as $25,00033 or as high as $1 million. 34 Some states lack an amount-in-controversy requirement altogether.35 Often, the amount-in-controversy requirement can vary from county to county, or from division to division, within the same state. For example, in Florida’s Eleventh Judicial Circuit of Florida (Miami), the minimum jurisdictional requirement is $750,000; in the Ninth Circuit (Orlando), the requirement is $500,000; the Seventeenth Circuit Page 7 of 25 (Fort Lauderdale) requires $150,000 to be eligible for the complex litigation division; and the Thirteenth Circuit (Tampa) does not have a minimum amount-in-controversy requirement.36

Other states, including Delaware’s CCLD, allow specified categories of cases to access a business court without regard to the amount in controversy. 37 In determining whether a given matter qualifies as a “business dispute,” numerous states have adopted guidelines wherein the central issues of the case must relate to matters such as:

- the formation, dissolution, governance, or liquidation of a business entity;

- obligations between a business entity and its owners, officers, directors, or partners;

- trade secrets, non-competes, or employment agreements;

- liability or indemnity of business entities or their owners, officers, directors, or partners; and

- disputes between business entities or individuals that relate to contracts or other transactions.

There are also states that require a specified amount in controversy plus certain eligibility criteria. For example, to be authorized to be heard by the Iowa Business Specialty Court, cases must involve claims for compensatory damages totaling $200,000 or greater and must fall into one of the following categories:

- Arise from technology licensing agreements, including software and biotechnology licensing agreements, or any agreement involving the licensing of any intellectual property right, including patent rights.

- Relate to the internal affairs of businesses (i.e., corporations, limited liability companies, general partnerships, limited liability partnerships, sole proprietorships, professional associations, real estate investment trusts, and joint ventures), including the rights or obligations between or among business participants, or the liability or indemnity of business participants, officers, directors, managers, trustees, or partners, among themselves or to the business.

- Involve claims of breach of contract, fraud, misrepresentation, or statutory violations between businesses arising out of business transactions or relationships.

- Be a shareholder derivative or commercial class action.

- Arise from commercial bank transactions.

- Relate to trade secrets, noncompete, nonsolicitation, or confidentiality agreements.

- Involve commercial real property disputes other than residential landlord-tenant disputes and foreclosures.

- Be a trade secrets, antitrust, or securities-related action.

- Involve business tort claims between or among two or more business entities or individuals as to their business or investment activities relating to contracts, transactions, or relationships between or among them.38

In some states, such as Arizona, 39 Indiana, 40 and Delaware,41 the courts outline which cases are eligible for their business court and which are not. Generally, the types of cases not eligible include: personal injury, survivorship, or wrongful death; product liability and consumer protection; discrimination; individual residential real estate disputes; matters eligible to be heard in family, probate, or juvenile courts; criminal matters; and consumer debts.

States with complex litigation courts will hear cases that are defined as, for example, “an action that requires exceptional judicial management to avoid placing unnecessary burdens on the court or the litigants and to expedite the case, keep costs reasonable, and promote effective decision making by the court, the parties, and counsel.”42 In these states, the court will assess whether a given case is sufficiently complex using various metrics, including: the number of parties and claims, amount in controversy, complexity of the legal and factual issues, transnational issues, complexity of the discovery, high volume of technical evidence, anticipated length of trial, number of witnesses, significant expert testimony, and amount of judicial supervision required pre- and post-judgment.43

While the subject matter of complex litigation courts and business courts are not identical, both courts’ objectives are similar—to provide specialized case law precedent and a forum where certain matters can be heard by a judge experienced in that particular proceeding.

Procedural Access Into (and Out of) Business Courts

The states that have established business courts have adopted varying methods for accessing a business court. Some states employ an “automatic” acceptance system, in which all cases satisfying certain pre-established criteria must be heard before a business court. Other states have adopted a more discretionary approach, in which either (1) a litigant can voluntarily choose or decline to initially file (or subsequently transfer) in the business court or (2) the state establishes a “gatekeeper” who recommends to the business court which applicants should have their cases heard there. And, in addition to getting commercial cases into the business courts, states have mechanisms for transferring cases out of these specialized courts. Arizona, Iowa, and North Carolina, for example, have different procedures for getting cases into and out of their business courts, as discussed in the following paragraphs.

Arizona

It is mandatory that a plaintiff filing a commercial case in Arizona’s Commercial Court include in the caption of the initial complaint the words “commercial court assignment requested,” assuring that a defendant who is served with the complaint will be aware of the potential assignment.44 The plaintiff must also check a box on the civil cover sheet that indicates the case is eligible for the business court.45 A defendant requesting commercial court assignment may file a notice within twenty days of making an appearance.46 Additionally, a judge may reconsider the commercial court assignment on motion of a party within a specified time limit.47 A judge with a general civil docket may also order transfer of a case to the commercial court on motion of a party or on the court’s own initiative.48 An assignment to the business court does not preclude subsequent transfer of an eligible case to the complex civil litigation program under Arizona’s Superior Court local rules.49

Iowa

Iowa has two avenues that parties may use to transfer a case into Iowa’s Business Specialty Court: (1) the case can be transferred if all parties consent to the transfer and the court administrator approves the transfer, or (2) a party may file a motion to transfer the case to the business court.50

Iowa’s business court allows a voluntary opt-in format in which all parties to an action agree to bring their legal dispute to the business court docket.51 The parties submit a Joint Consent for Case Assignment to the Iowa Business Specialty Court with the State Court Administrator, acknowledging that the case meets the necessary criteria. 52 There are no prescribed time limits for opting into the business court by joint consent.53 The administrator determines if the case may be transferred to the business court docket and, upon approval, assigns one of the business court judges to the case.54

If the parties do not jointly consent to transfer the case, a party may file a motion to transfer the case to the business court docket.55 The motion is filed in the case the same way as motions are usually filed, but the motion is ruled on by the chief judge of the judicial district in which the case is filed instead of the assigned district court judge.56 In the motion, the filer must certify that the case involves claims for compensatory damages totaling $200,000 or more or involves claims seeking primarily injunctive or declaratory relief, and that the case also satisfies one or more of the necessary criteria.57 The filer must also identify the status of the case and the names of any other parties joining in the motion. 58

A motion to transfer, unlike transferring by joint consent, does have prescribed time limits. The motion must be filed within 120 days of filing the petition or within thirty days of the service of an amended petition that adds claims or new parties.59 Once the motion is fully submitted, the chief judge of the judicial district in which the case is filed determines whether the case meets the necessary criteria.60

If a party files a motion to transfer, any other party may file a resistance to the motion within ten days after the motion has been served or within twenty days after the service of the motion, original notice, and petition upon the party, if the motion is filed with the petition.61 The chief judge of the judicial district in which the case is filed then rules on the motion with or without a hearing.62 The chief judge will enter an order with the court’s ruling and, if the motion is granted, notify the State Court Administrator, who will assign one of the business court judges to the case.63

North Carolina

North Carolina has procedures for getting a case back to regular civil superior court that was designated to the business court. The chief business court judge rules on oppositions to designation and may even determine sua sponte that the action should not have been designated as a mandatory complex business case in the first place.64 If the case is no longer designated as a mandatory complex business case, the action proceeds on the regular civil superior court docket in the county of appropriate venue.65 The parties may proceed with an interlocutory appeal regarding the chief judge’s decision on an opposition to designation.66

If a case meets the substantive requirements for mandatory complex business designation but a party fails to designate within the requisite period of time, the chief justice of the Supreme Court of North Carolina has discretion to designate any case as an “exceptional” or “complex business” case.67 A case that meets the requirements for designation as a “complex business case” may be assigned to a business court judge by the chief justice. The chief justice implemented a procedure that, absent exceptional circumstances, business court judges only are assigned those cases qualifying for complex business case designation (often referred to as “mandatory-mandatory” complex business cases).68

If a case is designated to the business court, the parties are not required to change venue and try the case in a business court courtroom. 69 The North Carolina Business Court is not a court of jurisdiction; it is an administrative division of the General Court of Justice.70 While motions and pretrial matters are typically heard in the business court courtroom of the presiding business court judge, all jury trials are held in the county of venue, and non-jury trials may be held in a business court courtroom if all parties consent.71

Selecting and Training the Judges

States vary in their selection of business court judges. These judges may be appointed by a state legislature or high court. For example, in Georgia, the court has a single judge who is appointed by the governor72; in West Virginia, the judges are appointed by the chief justice of the supreme court of appeals73; and in North Carolina, trial court judges are elected by the voters, but business court judges are nominated by the governor and confirmed by the general assembly. 74

Selection criteria also vary from state to state. In Georgia, a business court judge must meet three prerequisites to be appointed: (1) Georgia residency and U.S. citizenship for at least seven years; (2) admission to practice law in Georgia for at least seven years; and (3) fifteen years of legal experience in complex business litigation, either as an attorney or a judge.75

In Iowa, the supreme court appoints business court judges based on their educational background, experience in the adjudication of complex commercial cases, and their desire to participate in the business court.76 While serving on Iowa’s business court, the judges retain their normal district court dockets in addition to their business court dockets. 77 A committee chaired by a supreme court justice reviews applications for judgeship and makes a recommendation to the court on its decision regarding appointment.78 More specifically, district court judges—which includes business court judges—are appointed in Iowa considering the following:

Each judicial nominating commission shall carefully consider the individuals available for judge . . . . Such nominees shall be chosen by the affirmative vote of a majority of the full statutory number of commissioners upon the basis of their qualifications and without regard to political affiliation. Nominees shall be members of the bar of Iowa, shall be residents of the state or district of the court to which they are nominated, and shall be of such age that they will be able to serve an initial and one regular term of office to which they are nominated before reaching the age of seventy-two years.79

Business court judges sitting before these specialized cases will doubtless develop subject matter expertise, even if they lacked the specialization prior to sitting on that bench.80 Some states provide additional training for these judges to deepen their knowledge of business law and technology cases, for example.81 Judges appointed to the Maryland Business and Technology Case Management Program attend specialized training to help manage complex business and commercial litigation matters.82 And in Michigan, judges appointed to the business court must attend training provided by the Michigan Judicial Institute.83

Publishing Court Opinions

It is not enough for states to establish specialized courts. The next important aspect is for the courts to write and publish opinions. When a court neglects to publish decisions in its specialized areas of law, participants in that state (and in other states) are not afforded the full benefits of the court’s value. 84 As one observer put it:

In choosing where to do business, a company would logically prefer to do business in a state where the costs of litigation are lower, where a specialized judge was tasked with resolving its business disputes, and where there was a robust body of case law relating to business matters. To the extent that a business court satisfies each of these needs, it could serve as an effective tool for attracting businesses to a particular state. 85

. . .

When opinions are not published at all, the loss to the commercial community is obvious. When opinions are published seriatim on a state court website that is not searchable, then the loss is comparable. In today’s world, an opinion that is not searchable does not exist for all practical purposes. In order for business courts to fulfill their core function of providing greater certainty about the content of the business law of a particular state, it is necessary not simply that they write opinions but also—as importantly—that the state invest the time and resources in making sure that these opinions circulate as widely as possible. This means investing a sufficient amount in information technology to guarantee that these decisions can be located, searched, and read by local attorneys.86

Efforts in Texas to Adopt Business Courts

In almost every legislative session since 2007, Texas legislators have filed bills to create some type of business or complex litigation courts system in Texas. Senator Robert Duncan and Representative Dan Gattis filed companion bills S.B. 1204 and H.B. 2906 in the 2007 legislative session that would have, among other things, allowed specialized handling of complex civil cases. These two bills were based on the TLR Foundation’s report entitled The Texas Judicial System, Recommendations for Reform.

The bills proposed the creation of the Judicial Panel on Complex Cases, which would transfer complex cases to trial courts chosen by the Panel. 87 Under this proposal, a party seeking special handling of a case filed in any Texas trial court could ask the Panel to transfer the case to an assigned judge. The Panel, acting as a gatekeeper, had discretion to assign judges and transfer cases. The introduced version of S.B. 1204 required the supreme court to adopt rules regarding the types of civil cases that constituted complex cases and that, in developing the rules, consider certain factors with respect to the type of civil case, including:

- whether there are likely to be a large number of separately represented parties;

- whether coordination may be necessary with related actions pending in one or more courts in other counties, states, or countries, or in a United States federal court;

- Whether it would be beneficial for the case to be heard by a judge who is knowledgeable in the specific area of the law involved;

- whether it is likely that there will be numerous pretrial motions, or that pretrial motions will present difficult or novel legal issues that will be time-consuming to resolve;

- whether it is likely that there will be a large number of witnesses or a substantial amount of documentary evidence;

- whether it is likely that substantial post-judgment supervision will be required;

- whether it is likely that the amount in controversy will exceed an amount specified by the supreme court; and

- whether there is likely to be scientific, technical, medical, or other evidence that requires specialized knowledge.88

Senator Duncan successfully moved S.B. 1204 through the Senate, handing it off to Representative Gattis in the House. Unfortunately, S.B. 1204 failed to pass the House, dying on a point of order in the closing days of the legislative session.

The following legislative session, Senator Duncan carried S.B. 992, a new version of the courts bill that contained a mechanism for funding complex cases wherever the case was filed.89 The idea of the bill was to fund the particular court to handle the complex case instead of transferring the case out of that court. S.B. 992 also failed to be enacted.

In 2015 (H.B. 1603) and 2017 (H.B. 2594), Representative Jason Villalba unsuccessfully sponsored legislation to create statewide chancery courts. 90 Salient features of these bills included a $10 million minimum amount-in-controversy combined with a subject matter requirement.91 Only the following kinds of cases could be heard by the court Representative Villalba envisioned:

- a derivative action on behalf of an organization;

- an action arising out of or relating to a qualified transaction in which the amount in controversy exceeds $10 million, excluding interest, statutory damages, exemplary damages, penalties, attorney’s fees, and costs;

- an action regarding the governance or internal affairs of an organization;

- an action in which a claim under a state or federal securities or trade regulation law is asserted against:

(A) an organization;

(B) a governing person of an organization for an act or omission by the organization or by the person in the person’s capacity as a governing person;

(C) a person directly or indirectly controlling an organization for an act or omission by the organization; or

(D) a person directly or indirectly controlling a governing person for an act or omission by the governing person; - an action by an organization, or an owner or a member of an organization, if the action:

(A)is brought against an owner, managerial official, or controlling person of the organization; and

(B) alleges an act or omission by the person in the person’s capacity as an owner, managerial official, or controlling person of the organization; - an action alleging that an owner, managerial official, or controlling person breached a duty, by reason of the person’s status as an owner, managerial official, or controlling person, including the duty of care, loyalty, or good faith;

- an action seeking to hold an owner of an organization, a member of an organization, or a governing person liable for an obligation of the organization, other than on account of a written contract signed by the person to be held liable in a capacity other than as an owner, member, or governing person;

- an action in which the amount in controversy exceeds $10 million excluding interest, statutory damages, exemplary damages, penalties, attorney’s fees, and costs that:

(A) arise against, between, or among organizations, governing authorities, governing persons, members, or owners, relating to a contract transaction for business, commercial, investment, agricultural, or similar purposes; or

(B) involve violations of the Finance Code or Business & Commerce Code; - an action brought under Chapter 37, Civil Practice and Remedies Code, involving:

(A)the Business Organizations Code;

(B) an organization’s governing documents; or

(C) a dispute based on claims that fall within the provisions of this subsection; and - an action arising out of the Business Organizations Code. 92

Cases within the jurisdiction of the chancery court could be filed in that court. 93 If the court lacked subject-matter jurisdiction over even part of the matter, the case would be dismissed without prejudice.94 A party to an action filed in a district or county court at law that was within the subjectmatter jurisdiction of the chancery court could remove the action to that court; if the chancery court lacked jurisdiction, the court would remand to the originating court.95 Actions filed in the chancery court would be assigned to the docket of a judge on a rotating basis.96

Representative Villalba’s chancery court contained seven trial judges appointed for sixyear terms. 97 This aspect of the bill was controversial, as Texas elects all of its state-level trial and appellate judges. The bill outlined the necessary qualifications to be a judge on the business court, requiring the contender be: at least 35 years old, a U.S. citizen, a resident of Texas for at least two years before appointment, and a licensed attorney in Texas and have ten or more years of experience in (A) practicing complex civil business litigation; (B) practicing complex business transaction law; (C) teaching courses in complex civil business litigation or complex business transaction law at an accredited law school in this state; (D) serving as a judge of a court in this state with civil jurisdiction; or (E) any combination of this experience. 98

In 2019, Representative Jeff Leach sought to create a business district court and Court of Business Appeals, via H.B. 4149. 99 Substantively, H.B. 1603 (2015) as adopted by the House committee, H.B. 2594 (2017) as introduced, and H.B. 4149 (2019) as introduced are almost identical, including the list of cases that qualified for the specialized court. 100 The main difference was the nomenclature of “chancery court” versus “business court.”

Most recently, in 2021, Representative Brooks Landgraf carried H.B. 1875, a bill similar to Representative Leach’s H.B. 4149. 101 None of these efforts were successful, even though the bills were actively supported by the Texas Bar’s Business Law section and the Texas Business Law Foundation.102

Does Texas Need Business Courts?

Business courts could boost Texas’s economy, help the courts with overcrowded dockets, and create a fair and predictable forum for resolving certain kinds of disputes. And there is nothing controversial about having specialized courts. Texas already has civil courts, small claims courts, felony criminal courts, misdemeanor criminal courts, family courts, probate courts, juvenile courts, and veterans’ courts, among others.

Evolving, Complex Business Practices and Texas’s Economy

As interstate and international trade has grown increasingly complex, courts must likewise evolve to keep up—especially in Texas, where businesses are moving to the state daily. And while the litigants serviced by business courts are often large corporations, such entities play an oversized role in the economy, which affects all state residents.

Implementing specialized business courts allows a state to be viewed as a “preferred arena” for corporate litigation, by both lawyers and litigants.103 Because of the enhanced litigation efficiency and predictability provided by these courts, companies might consider the existence of the court as a reason to relocate to, or remain headquartered in, a particular state. To encourage more business growth and boost the economy in Texas, business courts should be established.

Judicial Efficiency and Precedential Consistency

Business courts allow disputes to be resolved in an expedited manner, saving both time and expense for the litigants. One important component driving efficiency is the involvement of a single judge, which reduces the litigants’ need to continually re-familiarize various jurists with the facts of their case. Further, specialized courts allow for the development of a cadre of knowledgeable and experienced judges, conversant in both business law and the handling of complex cases and dockets, resulting in faster, better-reasoned, and more predictable resolutions.

Along the same lines, companies highly prize “predictability” of judicial outcomes, which business courts encourage—especially in contrast to arbitration, the decisions of which lack precedential value—by repeatedly utilizing a finite number of judges and generating a body of coherent precedent. And the requirement of written trial-level opinions develops an extensive, internally coherent, and well-reasoned body of state commercial case law. With the great majority of modern cases now being resolved privately, the creation of such precedent is a benefit to the state. Moreover, because there would be predictability and the presence of experienced, business-knowledgeable judges, there is an increased probability of pre-trial settlement, as the judges can realistically assess each side’s likelihood of success.

Furthermore, diverting lengthy and complicated cases to specially-equipped business courts frees up non-specialized courts to more effectively and efficiently attend to other cases by unclogging their dockets. In seeking increased efficiency, business courts often serve as the proving grounds for emergent technology (such as video-conferencing, electronic filing, and searchable servers), which are later adopted on a statewide basis by all courts.

Although the business court model might raise fears of unfairly mismatched “David v. Goliath” battles between large corporations and individual consumers, the disputes would be between evenly-matched parties, i.e. corporation v. corporation, or corporation v. its owners, officers, or board.

Critics of Establishing Business Courts

There are some who criticize the creation of business courts.104 Opponents may say it is unfair to have “special courts” for business people or wrong to ask taxpayers to finance a specialized court system that provides them no apparent benefit. But the same disparity could be said for family courts, probate courts, and the like, which are already established, necessary, and funded by taxpayers.

Critics may argue that business court judges become isolated from hearing other areas of the law, while other judges are prevented altogether from hearing substantive business disputes. Relatedly, there could be worries that the most capable judges might move to the business courts, or that business courts could result in a small group of judges controlling the development of business law within that jurisdiction. However, first, it is arguably more important for judges to be skilled in specific areas of law (as it is already with family and probate judges, for example). Surely it is a beneficial aspect of a business court judge’s specialized position to focus on a niche of law rather than be somewhat familiar with myriad areas of civil law. Second, it is important that there is consistent development of business law.

Critics may also say business courts foster a public perception of pro-business favoritism or that such courts could encourage corporate forum shopping. However, as shown by the state of Delaware and discussed above, Texas, too, could represent a “gold standard” in deciding business disputes and pave the way to formulate instrumental business law precedent, making Texas an even-more-attractive location for businesses to incorporate and headquarter. A strong state economy benefits its residents.

It could also be said that adding business courts creates a two-tiered judicial system, where only business entities get quick, competent resolution, or that supplemental funding and superior technical and administrative resources may be appropriated from other courts. Actually, however, the creation of business courts would help other courts with their caseloads, thus enabling nonbusiness cases to obtain quick, competent resolution, too. Further, the implementation of business courts in Texas could take necessary and available resources into account and allocate accordingly to “underprivileged” courts.

Opponents may assert that hard statistical evidence supporting the alleged virtues of business courts, including efficiency and cost savings, is said to be inconclusive or absent. As examined above, it is difficult, if not impossible, to obtain hard statistical evidence because there are no consistent “business courts” across the U.S. However, proponents have said, for example, “A case that might take three, four, or five years in another state, we [in Delaware] can often do in eighteen months or less. [Business] disputes get heard quickly and fairly. A regular civil judge can’t give the big complex case the attention it needs. You’re always putting out fires.”105 And in Georgia, the business court found that it took an average 608 days for the court to handle complex contract cases, compared to an estimated 1,746 days on the general docket.106

Critics may argue that political appointments to specialized benches raise issues about potential bias, politicization, and the possibility of undue influence by special interest groups. A feasible option to avoid these issues is to appoint judges already on the bench or attorneys who are academically based.107 Regardless of how the judge is selected, “it must be done in a way that promotes the appearance of judicial independence and fosters public trust and confidence.”108

Lastly, critics could say that federal courts and alternate dispute resolution already exist to handle complex business litigation. However, as addressed throughout this paper, precedent in business law is important. With alternative dispute resolution, the outcomes are normally confidential and arbitrarily rendered. And in federal court, there are prerequisites that may not be met in order for the federal court to have jurisdiction.

The bottom line is that these courts, like family courts and probate courts, are beneficial. The specialized nature of business courts encourages judicial efficiency and allows the participating parties a fairer proceeding than if an unknowledgeable judge were to sit on the bench for the same case. A judge competent to handle business or complex litigation means consistency in precedent, and a business court streamlines the judicial process and allows resources to be spent more effectively.

Relationship of Business Courts to Other Procedures

Jury Trials

No modern-era business court automatically excludes a role for the jury, although some states allow both sides of the lawsuit to jointly consent to a bench trial. New Jersey implemented, then abandoned, a requirement that business court litigants waive their right to a jury trial.109 And even if requiring trials to the court were contemplated, it is not legally possible in Texas. The Texas Constitution guarantees a right to a jury if any party demands it, providing:

RIGHT OF TRIAL BY JURY. The right of trial by jury shall remain inviolate. The Legislature shall pass such laws as may be needed to regulate the same, and to maintain its purity and efficiency. . . . 110

Can a business court in Texas use a specialized jury? Although numerous commentators have called for utilizing “blue ribbon juries” made up of jurors possessing advanced degrees and specialized skills in cases involving complex technological and scientific issues,111 there does not appear to be any business court in the nation employing such specialized juries. And any effort to either eliminate or restrict a jury’s makeup doubtless opens the door to constitutional challenges.

Consequently, as both a practical and legal matter, a business court in Texas will have to provide for trials to a jury. But from what geographic area will the jury be chosen? In Representatives Villalba’s and Leach’s bills, examined above, a jury trial would be held in a county in which venue would be found under the general rules outlined in the Texas Civil Practice and Remedies Code; and the drawing of jury panels, selection of jurors, and other jury-related practice and procedure in the business court would be the same as for the district court in the county in which the trial would be held.112

Alternative Dispute Resolution

Business courts and alternate dispute resolution (“ADR”) share a number of goals, including reducing the litigants’ expenses, shortening the time needed to resolve disputes, and utilizing knowledgeable decision-makers. And it has been suggested that business courts are an exceptionally good fit for using ADR, given that (1) knowledgeable judges may be able to objectively identify the critical issues in dispute and thereby determine the optimal time for ADR (and perhaps even the ideal arbitrator), and (2) the “businessmen” on both sides of the dispute are presumably accustomed to negotiating.113

Indeed, a common feature of business courts in other states is the frequent use of courtordered ADR to encourage early case settlement. Some states have adopted ADR rules that are specific to their business courts.114 However, among the states that have adopted business courts, there is a wide variety of approaches to ADR. Submission to ADR, for example, may be optional or mandatory, and may involve any ADR mechanism from mediation or binding arbitration.

Despite their common goals, there are significant differences between the ADR process and proceeding in a business court. Utilizing a business court can involve a jury and an appeal, while ADR involves neither. A decision by a business court may be reported in a published opinion, while an ADR resolution is generally kept confidential, thereby hampering the development of business law within a state. Resolution by trial in a business court is necessarily adversarial, while the ADR process of mediation collaborative.

At any rate, the ADR component of business courts legislation in Texas likely does not require legislative action. Instead, it can be implemented by the business court judges themselves as is the case in other Texas courts. Most civil courts in Texas have local rules and standing orders relating to ADR, and there is no reason for business courts to operate differently in this respect.

Concluding Remarks

The Texas judiciary would greatly benefit from the adoption of business courts. Participants in these courts would be assigned judges with knowledge and expertise in both business law and effective case management. Texas could develop a centralized body of commercial precedent, which would incentivize companies to relocate to and incorporate in Texas, stimulating the state’s economy. Parties would have more certainty in the application of rules and procedures and a consistency in rule enforcement, thereby encouraging earlier settlement and less litigation costs. And the rest of the Texas judiciary would be more effective with less bogged down dockets. For these reasons, and so many more discussed herein, Texas should establish a business courts system.

ENDNOTES

1 The Texas Judicial System, Recommendations for Reform, TEXANS FOR LAWSUIT REFORM FOUND. (2007), https://tlrfoundation.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/tlrf_courtadmin2007_%C6%92_web.pdf.

2 See Tex. S.B. 1204, 80th Leg., R.S. (2007); Tex. H.B. 2906, 80th Leg., R.S. (2007).

3 These states include: Arizona, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, West Virginia, Wisconsin,

and Wyoming. See infra Table 1; see also Lee Applebaum et al., Through the Decades: The Development of Business Courts in the United States of America, 75 BUS. LAW. 2053, 2072–76 (2020); Jens Dammann, Business Courts and

Firm Performance 3 (U. Tex. L., L. & Econ. Res. Paper No. 564, 2017); Richard L. Renck & Carmen H. Thomas, Recent Developments in Business Commercial Courts in the United States and Abroad, A.B.A. (May 22, 2014), https://www.americanbar.org/groups/business_law/publications/blt/2014/05/01_renck/; Business and Commercial Litigation Courts: Course Curriculum, NAT’L CTR. FOR ST. CTS. (2020),

https://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/traffic/id/91. Arizona, California, Connecticut, Minnesota, and Oregon have complex litigation courts. See infra Table 1.

Jefferson County, Kentucky and the states of Tennessee and Wisconsin are currently undergoing pilot projects. See infra Table 1.

4 Benjamin F. Tennille et al., Getting to Yes in Specialized Courts: The Unique Role of ADR in Business Court Cases, 11 PEPP. DISP. RESOL. L.J. 35, 39 (2010).

5 Tyler Moorhead, Note, Business Courts: Their Advantages, Implementation Strategies, and Indiana’s Pursuit of Its Own, 50 IND. L. REV. 397, 406–07 (2016).

6 See generally John F. Coyle, Business Courts and Interstate Competition, 53 WM. & MARY L. REV. 1915 (2012).

7 Judicial Officers of the Court of Chancery, DEL. CTS., https://courts.delaware.gov/chancery/judges.aspx (last visited Dec. 13, 2021).

8 Id.

9 Id.

10 Jurisdiction of the Court of Chancery, DEL. CTS., https://courts.delaware.gov/Chancery/jurisdiction.aspx (last visited Dec. 13, 2021).

11 Id.

12 Id.

13 Court of Chancery, DEL. CTS., https://courts.delaware.gov/chancery/index.aspx (last visited Dec. 13, 2021).

14 Applebaum, supra note 3, at 2058.

15 Opinions and Orders, DEL. CTS., https://courts.delaware.gov/opinions/index.aspx?ag=court%20of%20chancery (last visited Dec. 13, 2021).

16 See Coyle, supra note 6, at 1925.

17 Coyle, supra note 6, at 1925. Delaware’s Complex Commercial Litigation Division of the Superior Court was actually modeled off New York’s Commercial Division to close Delaware’s jurisdictional gap.

18 See Applebaum, supra note 3, at 2058.

19 Complex Commercial Litigation Division (CCLD), DEL. CTS., https://courts.delaware.gov/superior/complex.aspx (last visited Dec. 13, 2021).

20 Id.

21 See id. As discussed above, Chancery Court disputes may be submitted to a jury heard in the Superior Court.

22 Id.

23 Id.

24 See Applebaum, supra note 3, at 2058–60.

25 See generally supra note 3.

26 See supra Table 1; see also Applebaum, supra note 3, at 2072–76.

27 Arizona has both a commercial court and a complex litigation court. See Lee Applebaum, Arizona Commercial Court in Maricopa County (Phoenix) Made Permanent, BUS. CTS. BLOG (June 11, 2019), https://www.businesscourtsblog.com/arizona-commercial-court-in-maricopa-county-phoenix-made-permanent/.

28 Because many commentators choose to indiscriminately classify these complex litigation courts as “business courts,” conducting a fully accurate census is difficult.

29 The pilot project concluded in 2015 without renewal. See The Colorado Civil Access Pilot Project Applicable toBusiness Actions in Certain District Courts, COLO. JUD. BRANCH,

https://www.courts.state.co.us/userfiles/file/Court_Probation/Educational_Resources/CAPP%20FAQs%20R8%2013 %20(FINAL).pdf (last updated Aug. 26, 2014).

30 See Dammann, supra note 3, at 7.

31 Examples include Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Fort Lauderdale. See Commercial Calendar Section, ST. ILL., CIR. CT. COOK CTY., https://www.cookcountycourt.org/about-the-court/County-Department/Law-Division/CommercialCalendar-Section (last visited Nov. 29, 2021); Commerce and Complex Litigation Center, FIFTH JUD. DIST. PENN., CTY. ALLEGHENY, https://www.alleghenycourts.us/civil/commerce_complex_litigation.aspx (last visited Nov. 29,

2021); Complex Litigation Unit, SEVENTEENTH JUD. CIR. FLA., http://www.17th.flcourts.org/circuit-civil-complexlitigation/ (last visited Nov. 29, 2021).

32 See Coyle, supra note 6, at 1937.

33 In Michigan, a case must be assigned to the business court if the amount in controversy is greater than $25,000 and all or part of the action includes a business or commercial dispute. See MICH. COMP. LAWS §§ 600.8035(1), 600.605, 600.8301(1).

34 In Georgia’s business court, where damages are requested, the amount in controversy must be at least $1 million for claims involving commercial real property or $500,000 for any eligible claims not involving commercial real property. GA. CODE ANN. § 15-5A-3(a)(1)(B).

35 For example, Maine lacks an amount-in-controversy requirement. See ME. R. CIV. P. 130 et seq.

36 See Fla. 11th Jud. Cir., Admin. Order 16-12 § 3 (Oct. 27, 2016),

http://www.jud11.flcourts.org/Administrative_Orders/2016-12- Reaffirmation%20of%20the%20Creation%20of%20the%20Complex%20Business%20Litigation%20SectionNo%20Signature.pdf; Fla. 9th Jud. Cir., Admin. Order 2019-08-02 ¶ I(A) (Nov. 20, 2019), https://www.ninthcircuit.org/sites/default/files/2019-08-02%20- %20Amended%20Order%20Regarding%20Business%20Court.pdf; Fla. 17th Jud. Cir., Admin. Order 2013-11-Civ ¶ (b)(5) (Mar. 11, 2013), http://www.17th.flcourts.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/2013-11-civ.pdf; Fla. 13th Jud. Cir., Admin. Order S-2013-021 ¶ 2 (Apr. 18, 2013), https://www.fljud13.org/Portals/0/AO/DOCS/2013-021-S.pdf.

37 While one of the options to get into Delaware’s CCLD is to have a claim with an amount in controversy of $1 million or greater, there are other avenues to maintain jurisdiction in that court. See supra p. 5; Complex Commercial

Litigation Division (CCLD), DEL. CTS., https://courts.delaware.gov/superior/complex.aspx (last visited Dec. 13, 2021).

38 In re Iowa Business Specialty Court, at ¶ E (Iowa Jan. 14, 2019) (mem.), https://www.iowacourts.gov/static/media/cms/011419_Business_Ct_Memo_5A469FC10871C.pdf.

39 The Arizona Commercial Court allows and precludes the following types of cases:

(b) Eligible Case Types. A commercial case is generally eligible for the commercial court if it meets one of the following descriptions:

(1) concerns the internal affairs, governance, dissolution, receivership, or liquidation of a business organization;

(2) arises out of obligations, liabilities, or indemnity claims between or among owners of the same business organization (including shareholders, members, and partners), or which concerns the liability or indemnity of individuals within a business organization (including officers, directors, managers, member managers, general partners, and trustees);

(3) concerns the sale, merger, or dissolution of a business organization, or the sale of substantially all of the assets of a business organization;

(4) relates to trade secrets or misappropriation of intellectual property, or arises from an agreement not to solicit, compete, or disclose;

(5) is a shareholder or member derivative action;

(6) arises from a commercial real estate transaction;

(7) arises from a relationship between a franchisor and a franchisee;

(8) involves the purchase or sale of securities or allegations of securities fraud;

(9) concerns a claim under state antitrust law;

(10) arises from a business contract or transaction governed by the Uniform Commercial Code;

(11)is a malpractice claim against a professional, other than a medical professional, that arises from services the professional provided to a business organization;

(12) arises out of tortious or statutorily prohibited business activity, such as unfair competition,n tortious interference, misrepresentation or fraud; or

(13) arises from any dispute between a business organization and an insurer under a commercial insurance policy, including an action by either the business or the insurer related to coverage or bad faith.

(c) Ineligible Case Types. A case that seeks only monetary relief in an amount less than $300,000 is not eligible for the commercial court. The following case types are generally not commercial cases unless business issues predominate:

(1) evictions;

(2) eminent domain or condemnation;

(3) civil rights;

(4) motor vehicle torts and other torts involving personal injury to a plaintiff;

(5) administrative appeals;

(6) domestic relations, protective orders, or criminal matters, except a criminal contempt arising in a commercial court case;

(7) wrongful termination of employment and statutory employment claims; or

(8) disputes concerning consumer contracts or transactions. A “consumer contract or transaction” is one that is primarily for personal, family, or household purposes. ARIZ. R. CIV. P. 8.1(b), (c).

40 Cases eligible for Indiana’s Commercial Court Docket include: Any civil case, including any jury case, non-jury case, injunction, temporary restraining order, class action, declaratory judgment, or derivative action . . . if the gravamen of the case relates to any of the following:

(A) The formation, governance, dissolution, or liquidation of a business entity;

(B) The rights or obligations between or among the owners, shareholders, officers, directors, managers, trustees, partners, or members of a business entity, or rights and obligations between or among any of them and the business entity;

(C) Trade secret, non-disclosure, non-compete, or employment agreements involving a business entity and an employee, owner, shareholder, officer, director, manager, trustee, partner, or member of the business entity;

(D) The rights, obligations, liability, or indemnity of an owner, shareholder, officer, director, manager, trustee, partner, or member of a business entity owed to or from the business entity;

(E) Disputes between or among two or more business entities or individuals as to their business activities relating to contracts, transactions, or relationships between or among them, including without limitation the following:

(1) Transactions governed by the Uniform Commercial Code, except for claims described in Commercial Court Rule 3(B) and 3(O);

(2) The purchase, sale, lease, or license of; a security interest in; or the infringement or misappropriation of patents, trademarks, service marks, copyrights, trade secrets, or other intellectual property;

(3) The purchase or sale of a business entity, whether by merger, acquisition of shares or assets, or otherwise;

(4) The sale of goods or services by a business entity to a business entity;

(5) Non-consumer bank or brokerage accounts, including loan, deposit, cash management, and investment accounts;

(6) Surety bonds and suretyship or guarantee obligations of individuals given in connection with business transactions;

(7) The purchase, sale, lease, or license of or a security interest in commercial property, whether tangible or intangible personal property or real property;

(8) Franchise or dealer relationships;

(9) Business related torts, such as claims of unfair competition, false advertising, unfair trade practices, fraud, or interference with contractual relations or prospective contractual relations;

(10) Cases relating to or arising under antitrust laws;

(11) Cases relating to securities or relating to or arising under securities laws;

(12) Commercial insurance contracts, including coverage disputes;

(13) Environmental claims arising from a breach of contractual or legal obligations or indemnities between business entities;

(14) Cases with a gravamen substantially similar to the foregoing (1 – 13) and not otherwise encompassed by Commercial Court Rule 3.

(F) Subject to acceptance of jurisdiction over the matter by the Commercial Court Judge, cases otherwise falling within the general intended purpose of the Commercial Court Docket wherein the parties agree to submit to the Commercial Court Docket. IND. COM. CT. R. 2. Cases not eligible for the Indiana Commercial Court Docket include: A civil case shall not be eligible for assignment into the Commercial Court Docket pursuant to Commercial Court 4 if the case does not relate to any of the topics provided under Commercial Court Rule 2, or the gravamen of the case relates to any of the following:

(A) Personal injury, survivor, or wrongful death matters;

(B) Consumer claims against business entities or insurers of business entities, including breach of warranty, product liability, and personal injury cases and cases arising under consumer protection laws;

(C) Matters involving only wages or hours, occupational health or safety, workers’ compensation, or unemployment compensation;

(D) Environmental claims, except as described in Commercial Court Rule 2(E)(13);

(E) Matters in eminent domain;

(F) Employment law cases, except those as described in Commercial Court Rule 2(C);

(G) Discrimination cases based upon the federal or state constitutions or the applicable federal, state, or political subdivision statutes, rules, regulations, or ordinances;

(H) Administrative agency, tax, zoning, and other appeals;

(I) Petition actions in the nature of a change of name of an individual, mental health act, guardianship, or government election matters;

(J) Individual residential real estate disputes, including foreclosure actions, or noncommercial landlord-tenant disputes;

(K) Any matter subject to the jurisdiction of the domestic relations, juvenile, or probate divisions of a court;

(L) Any matter subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of a city court, a town court, or the small claims division of a court;

(M) Any matter required by statute or other law to be heard in some other court or division of a court;

(N) Any criminal matter, other than criminal contempt in connection with a matter pending on the Commercial Court Docket;

(O) Consumer debts, such as debts or accounts incurred or obtained by an individual primarily for a personal, family, or household purpose; credit card debts incurred by individuals; medical services debts incurred by individuals; student loans; tax debts of individuals; promissory notes not primarily associated with purchasing an interest in a business; personal automobile loans; legal fees incurred for family or household purposes (such as probate, divorce, child custody, child support, criminal defense, negligence, and other tortious acts); and other similar types of consumer debts. IND. COM. CT. R. 3.

41 See supra p. 5; see also Complex Commercial Litigation Division (CCLD), DEL. CTS.,

https://courts.delaware.gov/superior/complex.aspx (last visited Dec. 13, 2021).

42 CAL. RULES OF COURT, rule 3.400(a).

43 See, e.g., id. rule 3.400(b), (c); OR. UNIFORM TRIAL COURT RULE 23.010(1); MINN. R. 146.02.

44 ARIZ. R. CIV. P. 8.1.

45 Id.

46 Id.

47 Id.

48 Id.

49 Id.

50 In re Iowa Business Specialty Court, at ¶ F (Iowa Jan. 14, 2019) (mem.), https://www.iowacourts.gov/static/media/cms/011419_Business_Ct_Memo_5A469FC10871C.pdf.

51 Id.

52 Id.

53 Id.

54 Id.

55 Id.

56 Iowa Business Specialty Court, IOWA JUD. BRANCH, https://www.iowacourts.gov/iowa-courts/district-court/iowabusiness-specialty-court (last visited Dec. 2, 2021).

57 Iowa Business Specialty Court, at ¶ F.

58 Id.

59 Id.

60 Id.

61 Id.

62 Id.

63 Id.

64 N.C. GEN. STAT. § 7A-45.4.

65 Id.

66 Id. § 7A-27(a).

67 N.C.R. PRAC. SUPER. & DIST. Ct. 2.1.

68 N.C. GEN. STAT. § 7A-45.4(b).

69 Business Court FAQs, N.C.JUD.BRANCH, https://www.nccourts.gov/courts/business-court/business-court-faqs(last visited Dec. 3, 2021).

70 Id.

71 Id.

72 See Applebaum, supra note 3, at 2065.

73 See Applebaum, supra note 3, at 2068.

74 See Business Court Judges, N.C. JUD. BRANCH, https://www.nccourts.gov/courts/business-court/business-courtjudges (last visited Dec. 2, 2021); Andrew Jones, Toward a Stronger Economic Future for North Carolina: Precedent

and Opinions of the North Carolina Business Court, 6 ELON L. REV. 189, 192, 199 (2014).

75 GA. CODE ANN. § 15-5A-6(c).

76 Iowa Business Specialty Court, IOWA JUD. BRANCH, https://www.iowacourts.gov/iowa-courts/district-court/iowabusiness-specialty-court (last visited Dec. 2, 2021).

77 Id.

78 In re Iowa Business Specialty Court, ¶ D (Iowa Jan. 14, 2019) (mem.), https://www.iowacourts.gov/static/media/cms/011419_Business_Ct_Memo_5A469FC10871C.pdf.

79 IOWA CODE § 46.14.

80 See Coyle, supra note 6, at 1978 n.242; see also Lawrence Baum, Judicial Specialization and the Adjudication of Immigration Cases, 59 DUKE L.J. 1501, 1538 (2010) (“Whether or not judges on a specialized court have prior experience in the field of their court’s work, they become specialists once they begin their judicial service.”).

81 See Coyle, supra note 6, at 1969.

82 See Applebaum, supra note 3, at 2063.

83 MICH. COMP. LAWS § 600.8043.

84 See Coyle, supra note 6, at 1938–39.

85 See Coyle, supra note 6, at 1939.

86 See Coyle, supra note 6, at 1956 n.164.

87 See Tex. S.B. 1204, 80th Leg., R.S. (2007); Tex. H.B. 2906, 80th Leg., R.S. (2007).

88 Tex. S.B. 1204, § 8.02, sec. 74.184 (introduced version).

89 Tex. S.B. 992, 81st Leg., R.S. (2009).

90 Tex. H.B. 1603, 84th Leg., R.S. (2015); Tex. H.B. 2594, 85th Leg., R.S. (2017).

91 Tex. H.B. 2594 (introduced version); see also Tex. H.B. 1603 (house committee report version).

92 Tex. H.B. 1603, § 1, sec. 24A.051 (house committee report version); see also Tex. H.B. 2594, § 1, sec. 24A.051 (introduced version). The house committee report version of H.B. 1603 and the introduced version of H.B. 2594 are nearly identical, including the list of eligible cases.

93 Tex. H.B. 2594, § 1, sec. 24A.052(a) (introduced version).

94 Id.

95 Id. sec. 24A.052(b).

96 Id. sec. 24A.052(f).

97 Id. secs. 24A.055, 25A.056.

98 Id. sec. 24A.054.

99 Tex. H.B. 4149, 86th Leg., R.S. (2019).

100 Compare Tex. H.B. 4149 (introduced version), with Tex. H.B. 1603 (house committee report version), and Tex. H.B. 2594 (introduced version).

101 Tex. H.B. 1875, 87th Leg., R.S. (2021).

102 Byron F. Egan, Texas Chancery Courts: The Missing Link to More Texas Entities, 79 TEX. B.J. 98 (Feb. 2016).

103 See generally Dammann, supra note 3.

104 See, e.g., David E. Chamberlain, Texas Chancery Courts: An Unconstitutional Money-Wasting Proposal, 79 TEX. B.J. 99 (Feb. 2016).

105 Jenni Bergal, States Set Up ‘Business Courts’ for Corporate Conflicts, STATELINE (Oct. 28, 2015), https://www.governing.com/archive/business-courts-take-on-complex-corporate-conflicts.html.

106 Id.

107 Anne Tucker Nees, Making a Case for Business Courts: A Survey of and Proposed Framework to Evaluate Business Courts, 24 GA. ST. U. L. REV. 477, 489 n.38 (2012).

108 Id.

109 See Coyle, supra note 6, at 1973–74 & n.226.

110 TEX. CONST. art. I, § 15.

111 See, e.g., Joshua L. Sohn, Specialized Juries for Patent Cases: An Empirical Proposal, 18 U. PA. J. BUS. L. 1175 (2016); Franklin Strier, The Educated Jury: A Proposal for Complex Litigation, 47 DEPAUL L. REV. 49 (1997); Jonathan J. Koehler, Train Our Jurors (Nw. U. Sch. L., Fac. Working Paper No. 141, 2006).

112 See Tex. H.B. 1603, 84th Leg., R.S., § 1, sec. 24A.063 (2015) (house committee report version); Tex. H.B. 2594, 85th Leg., R.S., § 1, sec. 24A.063 (2017) (introduced version); Tex. H.B. 4149, 86th Leg., R.S., § 1, sec. 24A.063 (2019) (introduced version).

113 See Tennille, supra note 4, at 104.

114 See, e.g., ILL. RULES OF THE COURT, rule 25.1 (Circuit Court of Cook County, Illinois); see also Tennille, supra note 4, at 72–96 tbl. 1