Evaluating Judicial Selection In Texas: A Comparative Study of State Judicial Selection Methods

FOREWORD

A young Abraham Lincoln, commenting on the recent passing of the last surviving Founding Father, James Madison, urged his audience to “let reverence for the laws … become the political reason of the Nation.” He observed that all should agree that to violate the law “is to trample on the blood of his father,” and that only “reverence for the constitution and laws” will preserve our political institutions and “retain the attachment of the people.”1

Lincoln knew that the law is the bedrock of a free society. Our judges are the guardians of the rule of law. If they do not apply the law in a competent, efficient, and impartial manner, trust in the rule of law will erode and society will fray. Therefore, our system for selecting and retaining judges should be based on merit and should encourage stability, experience, and professionalism in our judiciary.

The 86th Legislature created a special commission to study judicial selection, ensuring that the 87th Legislature in 2021 will consider judicial selection in Texas. The purpose of this paper is to discuss Texas’s current system of electing judges, to provide a summary of various judicial selection systems in other states, and to offer a compendium of research materials on this topic. Our intent is for this paper to assist the public debate and legislative consideration of how judges will be chosen in Texas in the future. There is no perfect system of selecting judges, no system in another state that Texas should adopt whole. But there is much to be learned by reflecting on our state’s experience in judicial elections and in the study of other states’ systems, which will help Texans develop a system with unique attributes that can become a model for the nation.

While it is not the purpose of this paper to make specific proposals for establishing a new system of judicial selection in Texas, we do believe that our current system of partisan election of judges does not place merit at the forefront of the selection process. How can it? Unquestionably, most voters—even the most diligent and informed ones—do not know the qualifications (or lack thereof) of all the judicial candidates listed on our ballots. This is especially true in our metropolitan counties, where the ballots list dozens of judicial positions. And even in our rural counties, voters are asked to make choices about candidates for our two statewide appellate courts and our fourteen intermediate appellate courts with little or no knowledge of the candidates for those offices.

The clearest manifestation of the ill consequences of the partisan election of judges is periodic partisan sweeps, in which nonjudicial top-of-the-ballot dynamics cause all judicial positions to be determined on a purely partisan basis, without regard to the qualifications of the candidates. A presidential race, U.S. Senate race, or gubernatorial race may be the main determinant of judicial races lower on the ballot. These sweeps impact both political parties equally, depending on the election year. For example, in the 2010 election, only Republican judicial candidates won in many Texas counties. In 2018, the opposite occurred and only Democratic judicial candidates won in many counties. These sweeps are devastating to the stability and efficacy of our judicial system when good and experienced judges are swept out of office for no meritorious reason. Nathan Hecht, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Texas, described this vividly in his State of the Judiciary Address to the 86th Legislature:

No method of judicial selection is perfect…. Still, partisan election is among the very worst methods of judicial selection. Voters understandably want accountability, and they should have it, but knowing almost nothing about judicial candidates, they end up throwing out very good judges who happen to be on the wrong side of races higher on the ballot.

Partisan sweeps—they have gone both ways over the years, and whichever way they went, I protested—partisan sweeps are demoralizing to judges, disruptive to the legal system, and degrading to the administration of justice. Even worse, when partisan politics is the driving force, and the political climate is as harsh as ours has become, judicial elections make judges more political, and judicial independence is the casualty. Make no mistake: a judicial selection system that continues to sow the political wind will reap the whirlwind.2

And there is this: judges in Texas are forced to be politicians in seeking election to what decidedly should not be political offices. They are not representatives of the people in the same way as are elected officials of the executive and legislative branches. A state legislator is to represent the interests and views of her constituents, consistent with her own conscience. A judge is to apply the law objectively, reasonably, and fairly—therefore, impartiality, personal integrity, and knowledge of and experience in the law should be the deciding factors in whether a person becomes and remains a judge. A judicial selection system should make qualifications, rather than personal political views or partisan affiliation, the paramount factor in choosing and retaining judges.

Over the past twenty-five years, Texas has led the way in restoring fairness to our civil justice system. We now have the opportunity to lead the way in establishing a stable, consistent, fair, highly qualified, and professional judiciary, keeping it accountable to the people, while also increasing integrity by removing it from the shifting winds of popular sentiment, electoral politics, and the need to raise campaign funds, all with the knowledge that the truest constituency of a judge is the law itself.

Hugh Rice Kelly and David Haug

Directors

Texans for Lawsuit Reform Foundation

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART I: INTRODUCTION

PART II: THE TEXAS JUDICIARY

Election of Texas Judges

Initial Appointment of Judges

Qualifications for Judicial Office

Seeking Election to Judicial Office

Campaign Contributions and Expenditures

Restrictions on Judicial Campaign Speech

Judicial Reelection

Judicial Incumbent Challenges

Removal of Texas Judges from Office

PART III JUDICIAL SELECTION PROCEDURES AMONG THE STATES

Historic Trends in Judicial Selection

Current Methods of State Judicial Selection

Current Variations of Judicial Selection by Gubernatorial Appointment

Current Variations of Judicial Selection by Legislative Appointment

Current Variations of Judicial Selection by Partisan Election

Current Variations of Judicial Selection by Nonpartisan Election

Current Variations of Judicial Selection by Missouri-Plan Appointment

Justice O’Connor Judicial Selection Plan

Use of Nominating Commissions in State Judicial Selection

Nominating Commissions Among the States

Missouri Plan States

Gubernatorial Appointment States

Traditional Election States

Legislative Appointment States

Number of Nominating Commissions Per State

Number of Commissioners

Selection of Commissioners

Composition of Commissions

Attorney and Lay Members

Partisanship

Gender, Race, and Ethnicity

Geography

Practice Area

Industry, Business, or Profession

Restrictions on Holding Public Office and on Nominations

Commissioner Terms

Recruiting Judicial Candidates

Retention of Judges

PART IV: EVALUATION OF SELECTION MODELS

A Method to Evaluate Selection Models

Evaluating Partisan Elections

Competence

Fairness

Independence

Accountability

Evaluating Nonpartisan Elections

Competence

Fairness

Independence

Accountability

Evaluating Gubernatorial Appointment

Competence

Fairness

Independence

Accountability

Legislative Confirmation

Evaluating Legislative Appointment

Competence

Fairness

Independence

Accountability

Evaluating the Missouri Plan

Competence

Fairness

Independence

Accountability

The Use and Effect of Retention Elections

The O’Connor Variant

PART V: CONCLUSION

ENDNOTES

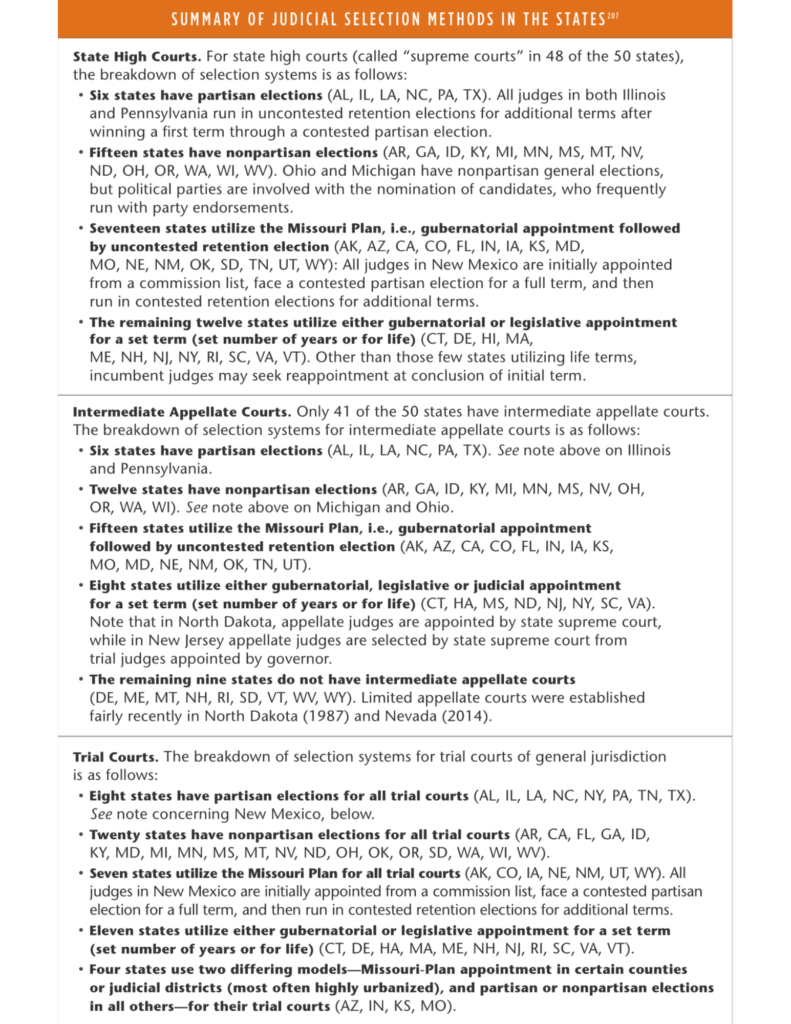

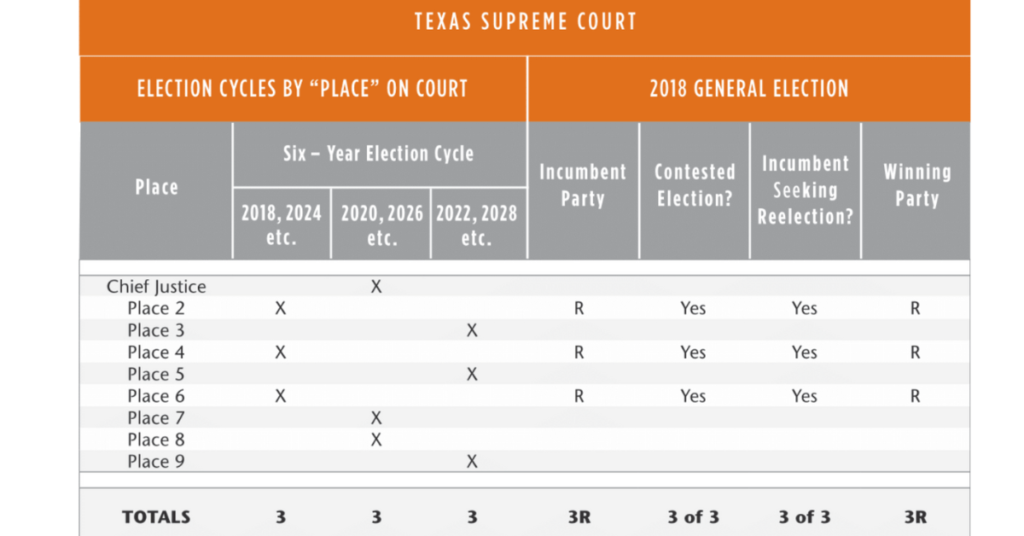

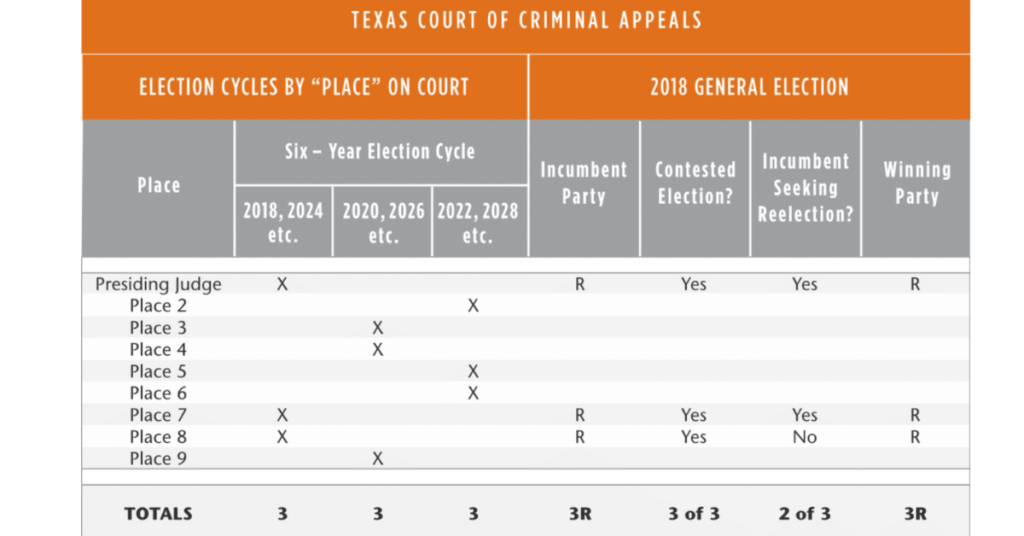

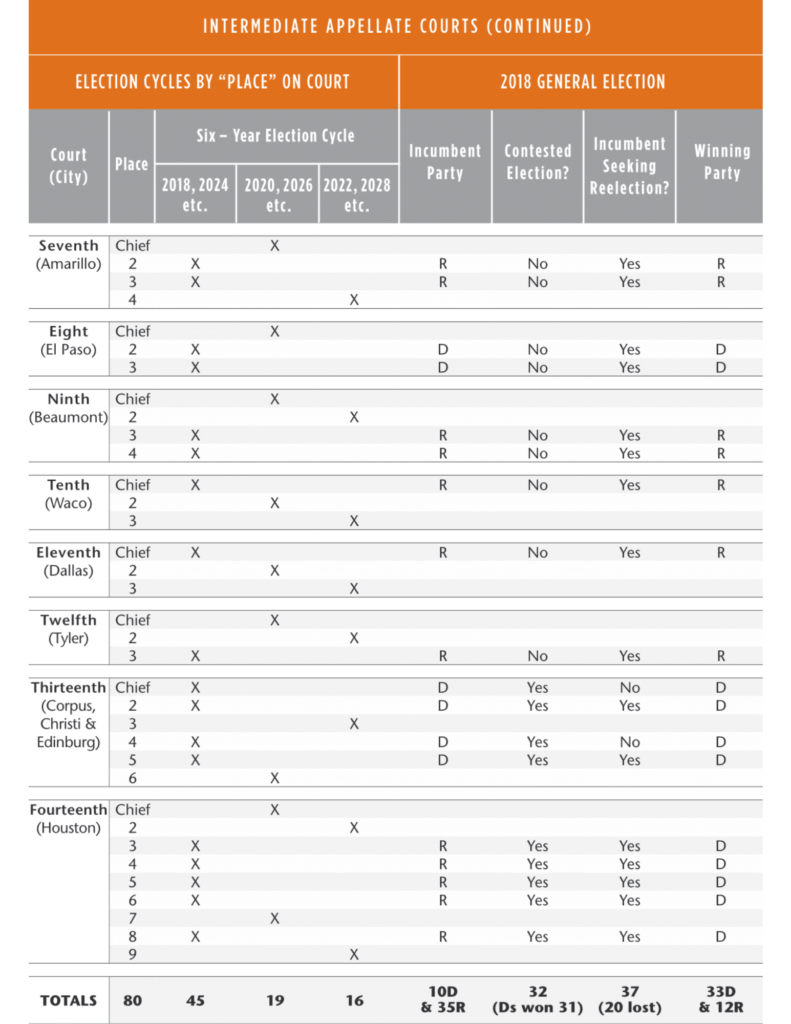

APPENDIX TABLE 1 Election Cycles for Places on Texas Appellate Courts & Results of 2018 General Election for Texas Appellate Courts

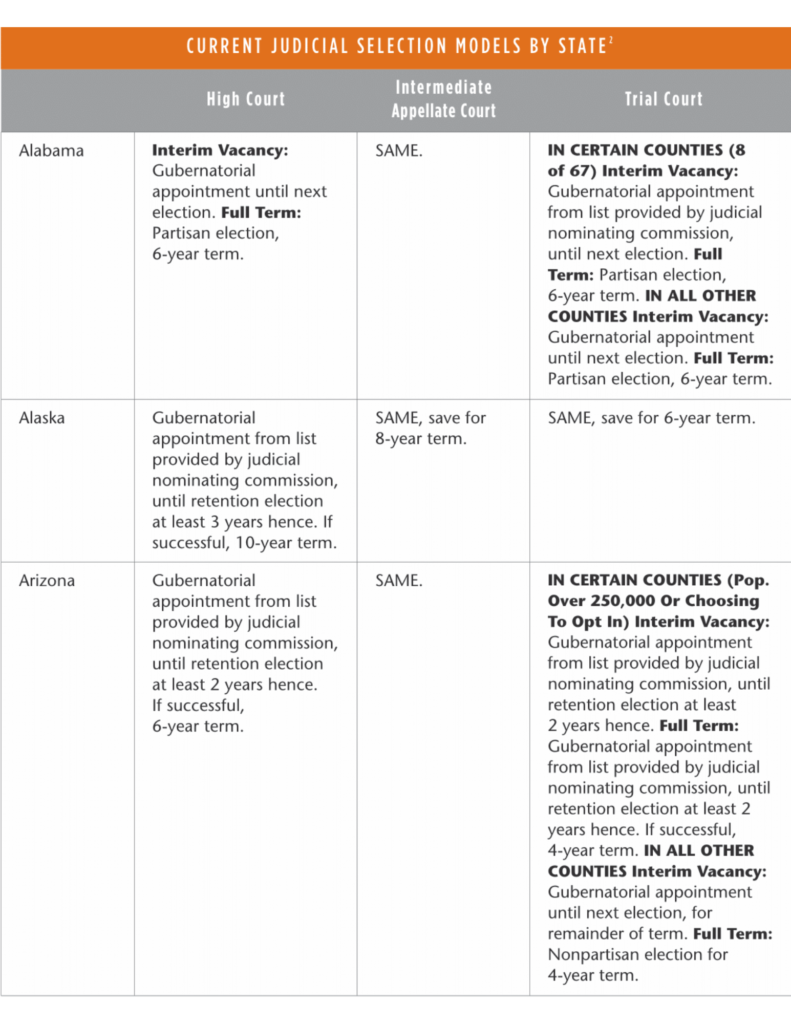

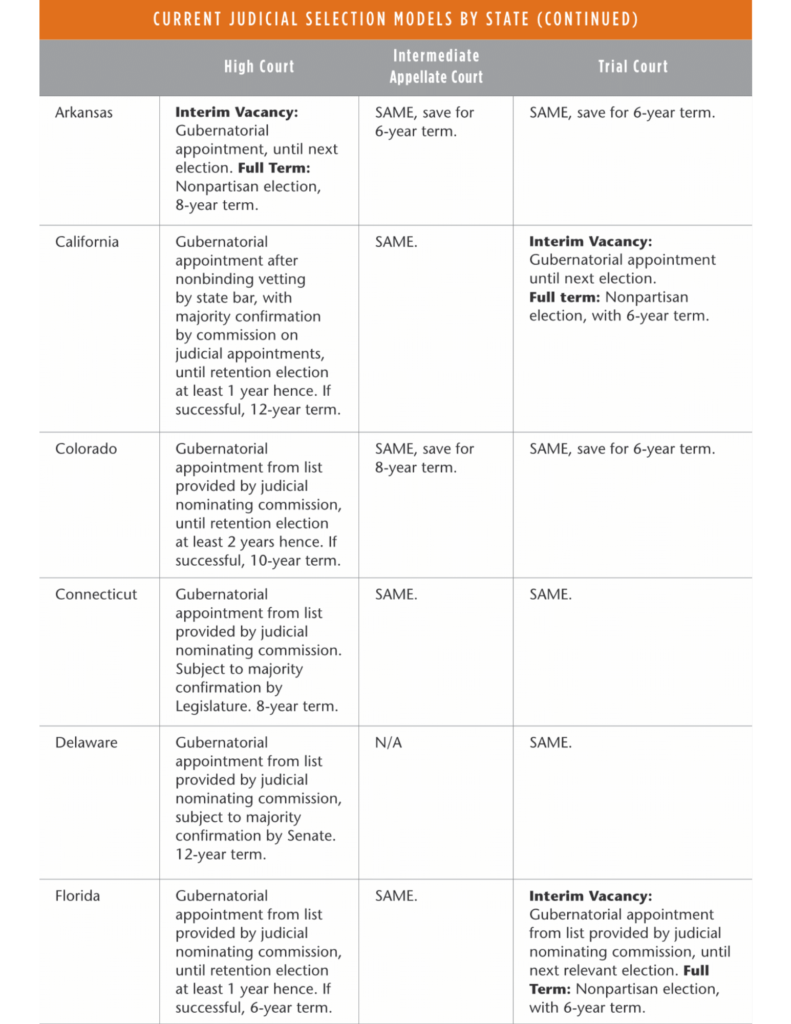

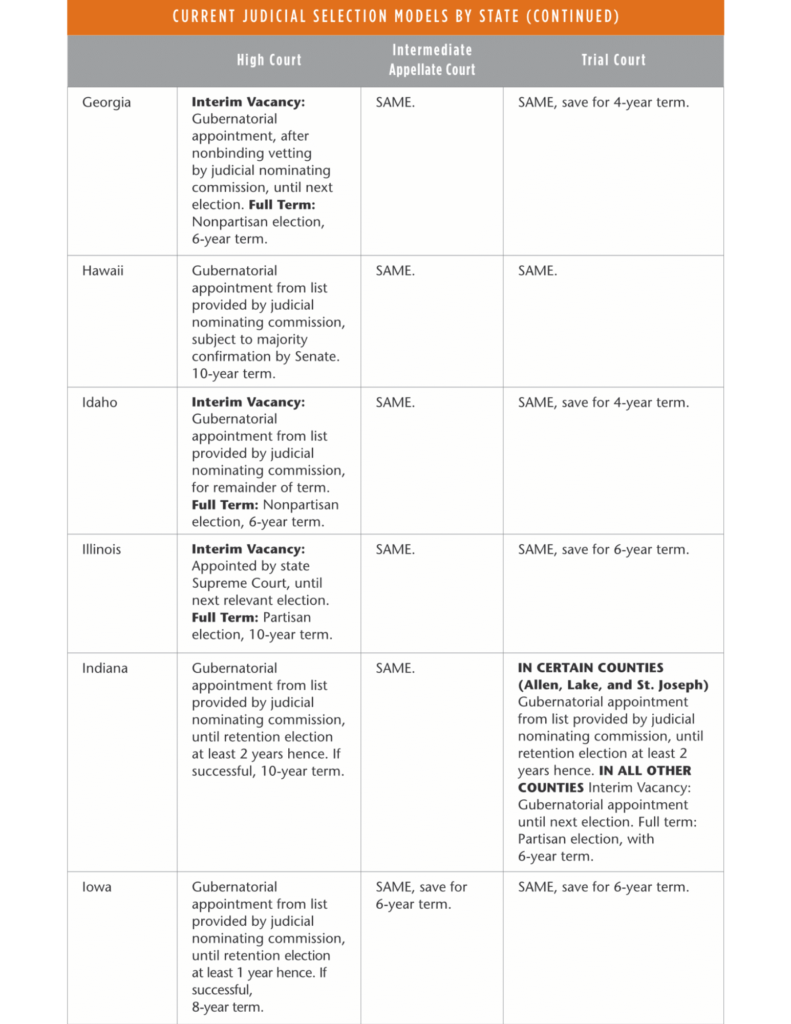

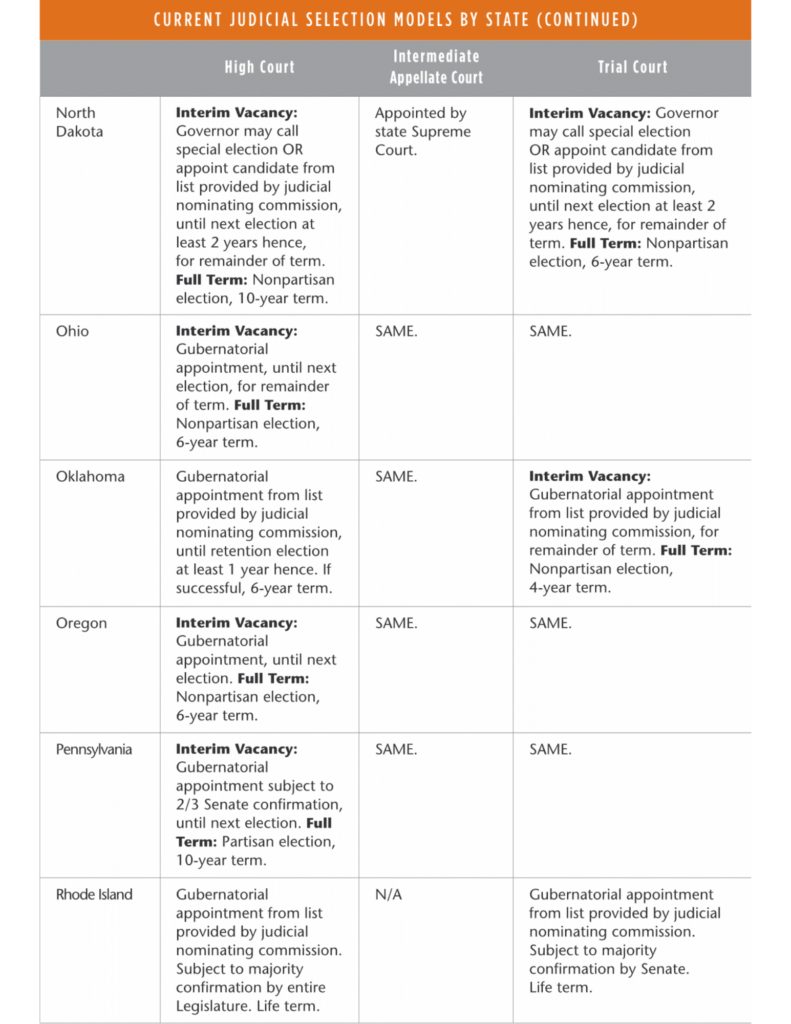

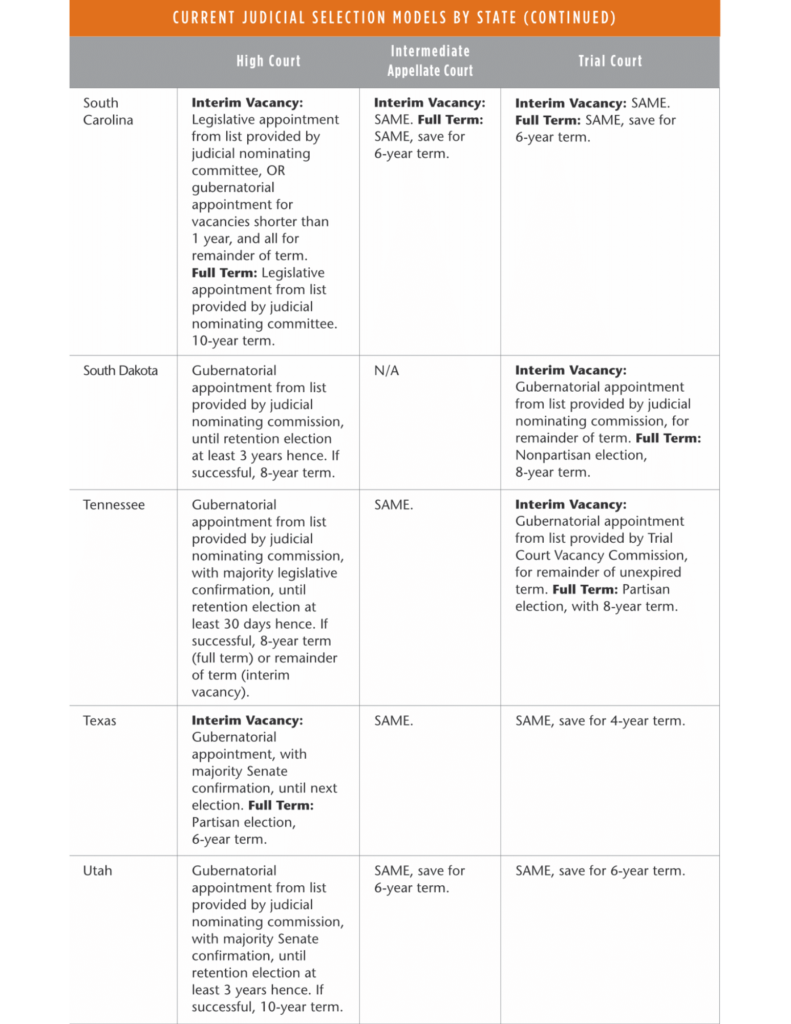

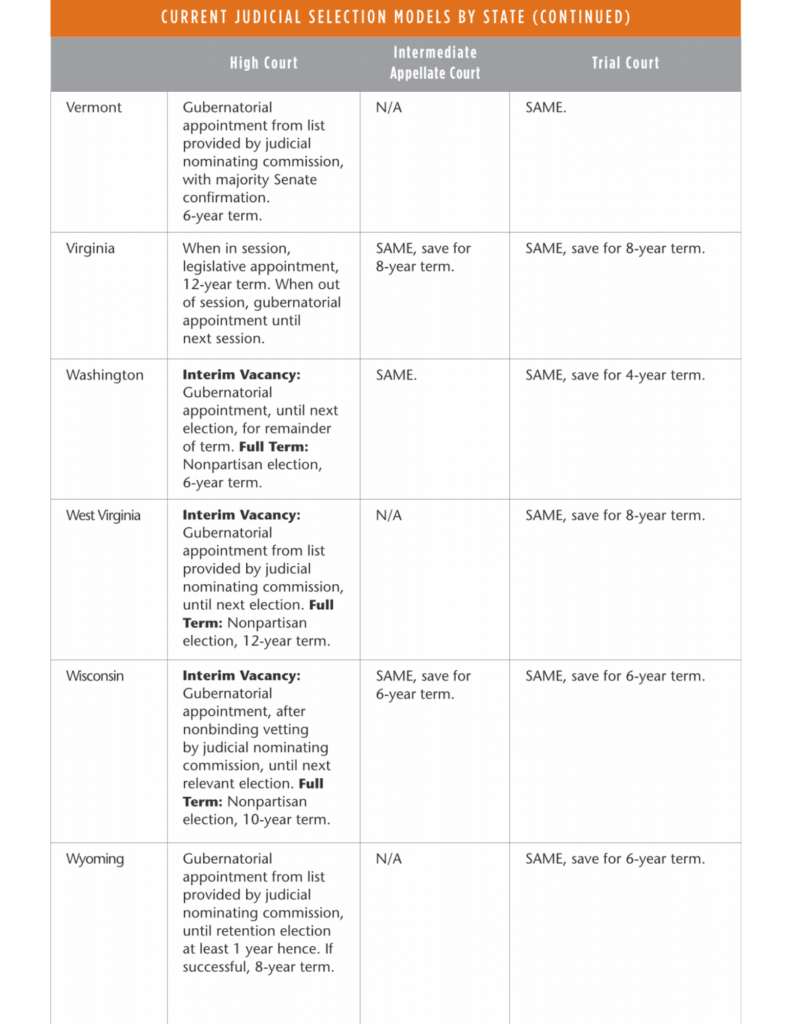

APPENDIX TABLE 2 Judicial Selection Models in the United States

PART I: INTRODUCTION

Movements to change Texas’s judicial selection system have been undertaken for decades.3 In 1946, following a five-year study of the state’s judicial system, the Texas Civil Judicial Council proposed amending the Texas Constitution to allow for gubernatorial appointment of judges followed by unopposed retention elections.4 Similar proposals were suggested in 1953, in 1971 by Chief Justice Calvert and the Task Force for Court Improvement, and in 1986 by Chief Justice John Hill and the Committee of 100.5 None of these movements succeeded.

Nonetheless, calls for change continued. Senators Robert Duncan (R-Lubbock) and Rodney Ellis (D-Houston) led a bipartisan effort to pass judicial selection reform through the Texas Legislature.6 In 1999, a bill was proposed providing for gubernatorial appointment of judges with senate confirmation and unopposed retention elections, which passed the Senate but stalled in the House.7 In 2001, the two senators proposed the same plan to apply only to Texas’s two highest courts: Supreme Court of Texas and Court of Criminal Appeals of Texas.8 Senator Ellis filed the same proposal to apply to all Texas courts in the 2003 and 2005 legislative sessions.9 Chief Justice Tom Phillips advocated for change during and after his tenure on the Supreme Court.10 None of these efforts succeeded, either.

In the last ten years, calls for reform by state leaders, at least five former Supreme Court justices, leaders of the State Bar of Texas, academic commentators, and public policy groups have continued.11 In 2013, former Supreme Court Chief Justice Wallace Jefferson noted that Republican and Democrat chief justices have been calling on the Texas Legislature for the last thirty years to change the way judges come to the bench in Texas and voiced his belief that the system is “broken” and should be changed.12

In November 2018, Texas voters swept dozens of incumbent judges from office, apparently based solely on the judges’ affiliation with a particular political party. Texas has eighty intermediate appellate court judges. Forty-five of these judgeships were on the 2018 ballot, with a contested election occurring in thirty-two of the forty-five seats.13 The candidate nominated by the Democratic Party won thirty-one of the thirty-two contested elections,14 including in districts where Republican candidates had dominated for years. Every incumbent Republican intermediate appellate court and trial court judge on the ballot in Harris County (Houston) was defeated.15 When all the new judges took office on January 1, 2019, about one-third of Texas’s 254 constitutional county judges were new and one-fourth of Texas’s district court, statutory county court, and justice court judges were, too.16 In total, 443 judges were new to the bench in Texas when they assumed office in January 2019.17 On the appellate and district courts, the Texas judiciary lost seven centuries of judicial experience in a single day.18

The November 2018 sweep of judicial offices was hardly unprecedented. In 1994, for example, Republicans won in forty-one of forty-two contested appellate court races in Texas.19 A 2017 analysis of elections held between 2008 and 2016 found dramatic sweeps to be the rule, not the exception. Focusing on Texas’s twenty most-populous counties, the study found that within any given jurisdiction where one or more judgeships was up for election (be that jurisdiction a county, an appellate district, or statewide), all judicial races within that jurisdiction were won by candidates from the same party approximately ninety-four percent of the time.20

Election results also show that the popularity of candidates at the top of the ballot (not the judicial candidates’ qualifications for office) greatly influences judicial elections down ballot.21 For example, when popular Democrat incumbent Lloyd Bentsen ran for reelection to the U.S. Senate in 1982, mostly Democratic judicial candidates prevailed.22 When Republican Ronald Reagan ran for reelection as president in 1984, Republican judicial candidates were more frequently elected.23 The 2018 sweep by Democrats appears to have been related in large part to the U.S. senatorial race between Republican Senator Ted Cruz and Democratic challenger Beto O’Rourke.24 Even though Cruz won the race, O’Rourke was more popular in the large urban counties and the Democratic judicial candidates swept those counties.

The election cycle itself appears to be a deciding factor in judicial election outcomes in some counties. For instance, Republican judicial candidates garnered the majority of votes cast in Harris County (Texas’s most populous county) in the 2010 and 2014 general elections— gubernatorial election years when voter participation was modest.25 Democratic judicial candidates, on the other hand, gathered the majority of votes in most races in the 2012 and 2016 general elections—presidential election years in which a larger numbers of voters participated.26 The back-and-forth pattern—wholly unrelated to the qualifications of any of the judicial candidates—changed in 2018, when candidates fielded by the Democratic Party swept judicial races in Harris County, even though it was a gubernatorial election year.27

History proves that these partisan swings will continue to happen in Texas, sometimes sweeping in Republican judicial candidates and sometimes sweeping in Democrats, undermining the stability of the judiciary, discouraging many qualified lawyers from seeking judicial office, and diminishing the development of an experienced and professional judicial branch.

In response to the most recent upheaval in the Texas judiciary, the Texas Legislature passed a bill during the 2019 legislative session establishing the Texas Commission on Judicial Selection to study and review the method by which appellate court judges and trial court judges having county-wide jurisdiction are selected for office in Texas.28 The Commission must submit its findings to the Governor and Legislature no later than December 31, 2020,29 so that the Legislature may consider its recommendations during the next legislative session, which begins on January 12, 2021.

This paper provides in Part II an overview of Texas’s judiciary, the method used in Texas for selecting and removing judges, and other information concerning Texas’s judiciary. In Part III, the paper summarizes the various judicial selection systems used in other states, which fall into two general categories of selection by election and selection by appointment. The Missouri Plan, which is a method using appointment and retention elections, is used in numerous states and discussed in detail.

Part IV provides a method for evaluating the various judicial selection methods. The major methods currently in use—partisan election, nonpartisan election, gubernatorial appointment, legislative appointment, and the Missouri Plan—are evaluated to determine how likely each is to yield judges who are competent, fair, independent, and accountable.

PART II: THE TEXAS JUDICIARY

In evaluating whether Texas’s method of selecting judges can be improved, it is necessary to understand the current method of judicial selection and how it operates in practice. Texas is:one of only six states that select all of the judges in their judicial branch via partisan elections.30 However, while the Texas Constitution expressly provides that Texas’s judges are to be elected to office,31 the constitution also allows interim court vacancies to be filled through appointment by the Governor or county officials,32 as opposed to interim elections generally used to fill vacancies in other branches of Texas government.33 The frequency with which interim judicial appointments occur, when combined with the low percentages of contested elections involving those who have been appointed, suggest that it is a misconception to think Texas has a purely elective judicial selection system.

Election of Texas Judges

The current Texas Constitution mandates that Texas judges are to be selected for office by general election.34 Texas, however, has not always elected its judges. During the Republic era, from 1836 to 1846, the Texas Legislature appointed appellate judges, but not trial judges.35 When Texas became a state in 1846, its new constitution provided for gubernatorial appointment of judges with the concurrence of the Senate.36 Four years after that, in response to sweeping judicial selection changes across the county, Texas adopted a partisan election-based method for selecting judges.37 Then, in 1861, when Texas joined the Confederacy, its new constitution returned to the selection of judges by gubernatorial appointment with Senate approval,38 and the 1869 Reconstruction constitution continued this system.39 In 1876, Texas adopted its current constitution, which provides for election-based judicial selection.40

The requirement to stand for election applies to all judges whose office is created under Article V of the Texas Constitution: justices on the Supreme Court of Texas, judges on the Court of Criminal Appeals of Texas, justices on the fourteen intermediate appellate courts, judges on the district courts, statutory county courts and statutory probate courts, constitutional county court judges, and justices of the peace.41

Nearly every state in the Union has tried partisan elections for selecting judges at some point in the past 150 years.42 However, most of the other states have since adopted some other judicial selection system.43 Texas is one of only a few states to continue to select all of its constitutional judges through partisan elections.44 Aside from small changes to the Texas judicial selection system since its rebirth in 1876, the fundamental features of the system have remained unchanged for more than 140 years.

Texas has a total of eighteen judges on its two high courts: nine each on the Supreme Court (which has jurisdiction over civil matters) and the Court of Criminal Appeals (which has jurisdiction over criminal matters), who are elected to six-year terms.45 The elections for these offices are staggered so that three judges from each court are scheduled for election in each biennial general election.46

Texas has fourteen intermediate courts of appeals.47 The eighty justices of these courts of appeals are also elected to six-year terms.48 Intermediate appellate court elections are staggered, but somewhat unevenly. About half of these positions are filled in one election intervening election cycles (2020, 2022, 2026, 2028, etc.).49

At the trial court level, Texas has 1,794 Article V judges serving on 472 district courts, 254 constitutional county courts, 247 statutory county courts, 18 statutory probate courts, and 803 justice courts, all of whom are elected for four-year terms, such that about half of the trial judges serving full terms are up for election every two years.50 However, in any given biennial general election, more than half the total number of the trial court judges will be on the ballot because a significant portion of Texas judges are initially appointed to fill vacancies and must stand for reelection in the next general election, rather than serving out the remainder of the departing judge’s term.

Initial Appointment of Judges

While all Texas judges ultimately stand for election, judges can initially be selected for judicial office either by general election or appointment to fill a vacant position.51 Interim vacancies arise when the preceding judge vacates her seat prior to completing her term, whether due to death, illness, retirement, resignation, or appointment to another office.

The Governor is authorized to appoint individuals to fill interim vacancies on the Supreme Court, Court of Criminal Appeals, the intermediate courts of appeals, and district courts.52

When vacancies occur in county-level courts—including statutory county courts (also called “county courts at law”), probate courts, constitutional county courts, and justice courts—the

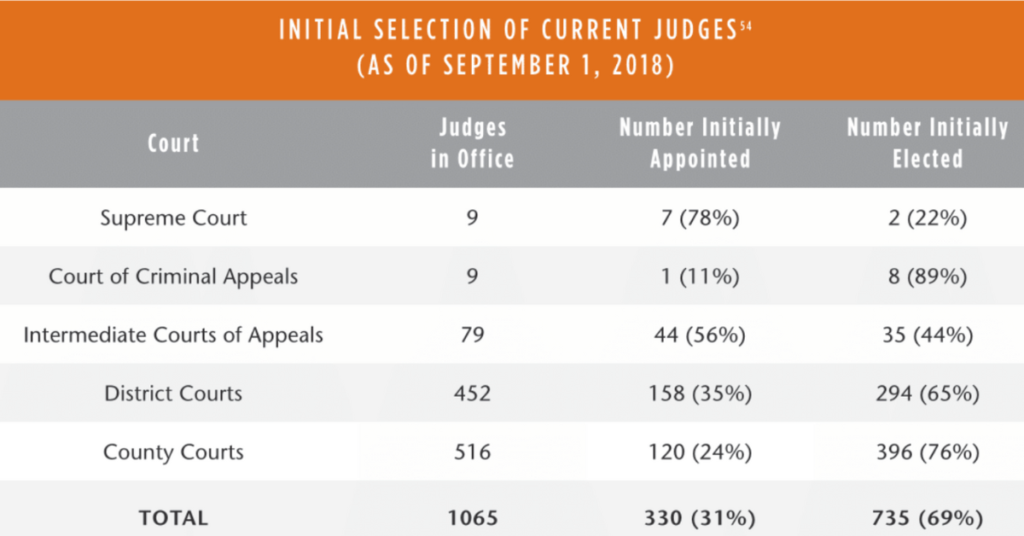

Commissioners Court in that county is entitled to appoint the replacement.53 As the following table shows, thirty-one percent of Texas’s Article V judges (excluding justices of the peace) as of September 1, 2018 first came to the bench via an interim appointment.

An individual appointed to fill a court vacancy is entitled to remain on the bench until the next general election.55 For example, if a court of appeals justice resigns in 2019 during the first year of a six-year term of office, the Governor’s appointee to fill the vacancy would be entitled to maintain that office only until the next general election in 2020. The winner of the 2020 election would then be entitled to maintain the office for the remaining four years of the vacated six-year term, after which the seat would again be up for election in 2024. The winner of the 2024 election would then be entitled to hold the office for a full six-year term. The percentage of judges who were initially appointed to office varies by the type of court. For example, seven of the nine Supreme Court justices were initially appointed to their positions, whereas only one of the Court of Criminal Appeals judges was initially appointed.56

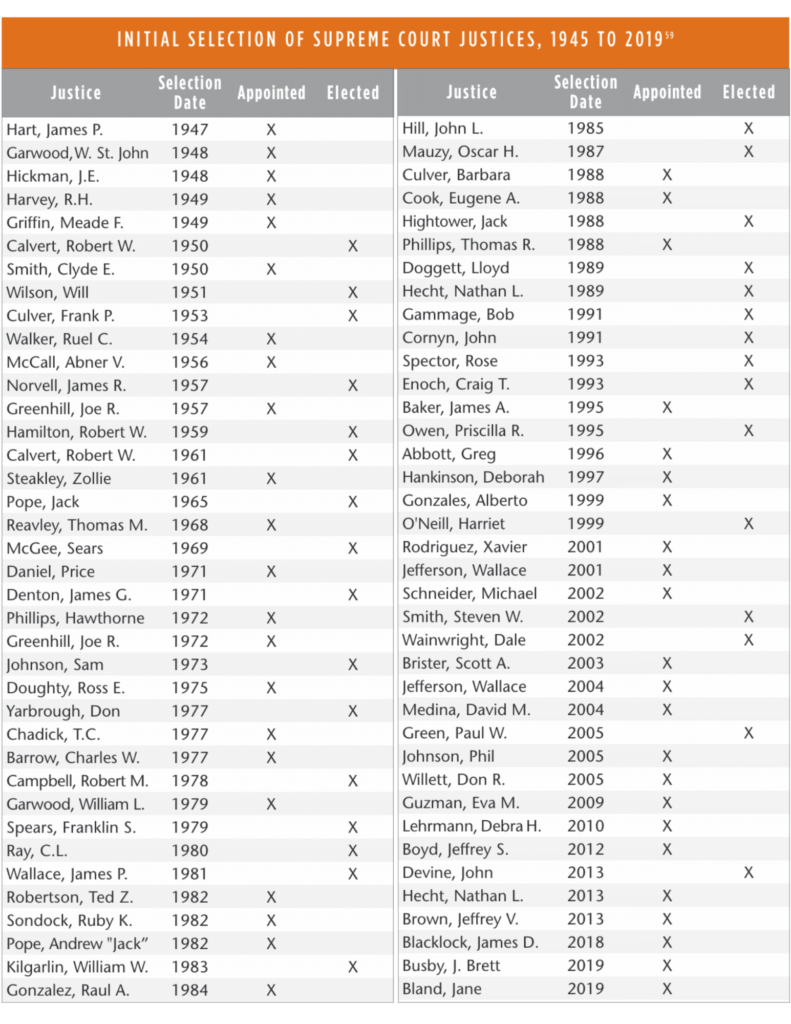

Additionally, as of September 1, 2018, fifty-six percent of intermediate appellate court justices were initially appointed to the bench by the Governor, as were thirty-five percent of Texas district court judges.57 While such initially appointed judges soon face election, the election may or may not be contested. These statistics have led some commentators to conclude that, beneath its elective veneer, Texas’s judicial selection mechanisms are, in fact, often appointive in nature.58 The preceding chart summarizes the initial selection process of Texas Supreme Court justices from 1945 to 2019. Over the seventy-two-year period, forty- five of seventy-six justices—fifty-nine percent—were initially appointed to the office.

Qualifications for Judicial Office

To be qualified for election or appointment, a candidate for judicial office must satisfy certain requirements set out in the Texas Constitution and the Texas Government Code. All Texas judges must be citizens of the United States and reside in the state of Texas, and apart from constitutional county courts and justice courts, which are discussed below, must be licensed to practice law in Texas.60 Judges on the two high courts and the intermediate appellate courts must also be at least thirty-five years old and must have been a practicing lawyer or judge of a court of record for at least ten years prior to taking office.61

Texas trial court judges must satisfy similar, but less strict, qualification standards. A district court judge need only be twenty-five years old and have at least four years of experience as a practicing lawyer or judge of a Texas court.62 Additionally, a district judge must reside in the district to which elected while serving in that office.63 Similarly, a county court at law judge must have at least four years of experience and must also have resided in the county where the court is located for at least two years before taking the bench.64

The only requirement for a constitutional county court judge is that the person is “well informed in the law of the State.”65 The Texas Constitution does not set out qualifications for justices of the peace, and so the generally applicable qualifications statute applies to these judges.66 Thus, a justice of the peace must be a United States citizen who has resided in the state and district for which election is sought for at least twelve months. A justice of the peace must be at least eighteen years of age, not mentally incapacitated, and not a felon.67

The constitutional and statutory minimum qualifications for judicial office in Texas are somewhat similar to the standards imposed by other states.68 Most, but not all, require a judicial candidate to be a resident of the state and to have a certain number of years in practice (typically between five and ten) before becoming eligible to serve as an appellate judge.69 For trial court candidates, experience as a practicing lawyer is likewise required, but the requisite number of years is usually reduced.70

Notably, certain criteria are not mandatory qualifications for becoming a judge in Texas or other states. For example, no state requires that its judges have any specific type of legal experience—such as litigation or appellate experience—or to be certified or specialized in any particular field.71 Additionally, almost no states require that their high court and appellate judges have previous judicial experience.72 New York and New Jersey, however, require that appointments to their intermediate courts of appeals must come from their existing pool of trial court judges.73

Although not mandated, many Texas judges nonetheless do have prior judicial experience. 74 As of September 1, 2018, twenty-seven percent of the judges on Texas’s intermediate courts of appeal served on a lower court immediately prior to taking their seat and eleven percent of district court judges had previously served on a lower court.75

Seeking Election to Judicial Office

A qualified candidate seeking election to a Texas court must win a plurality of votes in the general election for the judicial office.76 In seeking to have his or her name put on the ballot for a general election, there are two paths a candidate can pursue. First, a candidate can seek the nomination of a political party.77 In Texas judicial elections, the overwhelming majority of candidates choose this route.78 Second, a candidate can campaign as an independent and obtain a spot on the general election ballot without first seeking a political party nomination.79

Candidates seeking the nomination of the Republican or Democratic Party must run for nomination in the party’s primary election.80 To be listed as a candidate on a party’s primary ballot, a candidate must first file an application to be placed on the ballot.81 Certain judicial candidates must also file a petition signed by qualified voters supporting the candidate’s placement on the ballot.82 A candidate for the Supreme Court or Court of Criminal Appeals, for example, must obtain at least fifty signatures from qualified voters in each of the fourteen courts of appeals districts.83 Judicial candidates seeking a seat on an intermediate court of appeals, district court, or county court at law that includes a county with a population exceeding certain thresholds (of 1.0 or 1.5 million) must obtain at least 250 petition signatures. 84 Candidates seeking judicial positions in less populated areas, however, may need to obtain as few as fifty signatures.85 Additionally, judicial candidates seeking a party nomination may be required to pay that party a filing fee, ranging from $2,500 for statewide judicial office to $1,500 for small-county trial court positions.86 However, candidates for positions on certain intermediate courts of appeals and trial courts can avoid these filing fees by submitting petition signatures.87

To obtain the Republican or Democratic Party nomination for the general election, a judicial candidate must receive a majority of the total votes cast in the primary election.88 In the event no candidate receives a majority of the initial primary votes cast, the two candidates who received the most votes must participate in a runoff primary election.89 The candidate who obtains a majority of the votes cast—either in the primary election or the runoff election—is the party’s nominee for the judicial office in the general election.90

A judicial candidate running as an independent must file both a declaration of intent to run as an independent candidate and an application for a place on the general election ballot, which application includes the candidate’s name, occupation, date of birth, residence, office sought, and a sworn representation that the candidate satisfies the requirements for that office.91 Additionally, an independent candidate must file a petition supporting her placement on the ballot, signed by qualified voters who did not vote in any party primary election that nominated a candidate for the same race.92 When seeking a statewide judicial position, an independent candidate must obtain a number of signatures equal to one percent of the total vote received by all candidates for governor in the most recent gubernatorial general election.93 For other judicial positions, the independent candidate must obtain between twenty-five and 500 signatures, depending on the total vote for governor cast in that district or county in the most recent gubernatorial general election.94

Campaign Contributions and Expenditures

One feature that distinguishes judicial elections from other elections in Texas is the regulation of campaign contributions and expenditures. In general, Texas law does not limit the amount of money a candidate for state office may accept in campaign contributions or spend on campaigning. However, concerns regarding unlimited fundraising in judicial campaigns have received significant attention from the media, government officials, citizens, and interest groups. In the 1980s in particular, Texas was the focus of national media reports questioning whether large judicial campaign contributions from a small number of lawyers jeopardized judicial independence.95 The perception that contributions to judicial campaigns result in preferential treatment for contributors persists today.96

In an effort to control the perceived problems related to unlimited contributions to candidates for Texas’s Supreme Court, Court of Criminal Appeals, intermediate appellate courts, district courts, and statutory county courts, the Texas Legislature enacted the Judicial Campaign Fairness Act in 1995.97 As initially enacted, the statute capped contributions to a judicial candidate and restricted independent expenditures made in support of a judicial candidate.98 It also provided for voluntary compliance by judicial candidates with expenditure limits.99 The statute was amended in 2019 to repeal the restrictions on independent expenditures and the voluntary compliance provisions.100 Limitations on independent expenditures have been held to be unconstitutional101 and the voluntary expenditure limits were meaningless given that the tight contribution limits effectively prevent most judicial candidates from raising sufficient funds to reach the expenditure limits.

After the 2019 amendments, the Judicial Campaign Fairness Act still limits contributions to judicial candidates.102 These limits vary depending on the particular office sought and, in some cases, the population of the area served by the court.103 In addition to limiting the total amount of campaign contributions, the law limits the amount of contributions a candidate can receive from specific sources, such as individuals, law firms, and political action committees.104

For example, a judge on the Supreme Court or Court of Criminal Appeals may accept a maximum of $5,000 in an election from an individual, a maximum of $25,000 from a political action committee (PAC), and a maximum of $300,000 in total from all contributing PACs during the election.105 A person running for a trial court bench in a district having a population of less than 250,000 can accept only $1,000 from an individual, $5,000 from a PAC, and $15,000 in total from all PACs.106 The contribution limits of the Judicial Campaign Fairness Act apply to a single election cycle.107 Thus, a candidate can raise up to the statutory limits for each primary election, runoff election, and general election.108 However, the primary and general elections are considered to be one election for the purposes of calculating contribution limits under the law, if the candidate is unopposed in these elections.109

In addition to limiting the amount of contributions judicial candidates can accept, the Judicial Campaign Fairness Act also establishes limits on when a candidate can accept contributions.110 In general, a judicial candidate is prohibited from accepting contributions when not involved in a campaign. Specifically, a candidate cannot accept a contribution more than 210 days prior to the deadline for filing an application for a place on the ballot.111 Additionally, a judicial candidate cannot accept a contribution 120 days after the date of the election in which the candidate last appeared on the ballot.112

Restrictions on Judicial Campaign Speech

Another significant difference between judicial elections and other elections in Texas is the restriction on certain types of statements that a judicial candidate can make in the context of a campaign. Since the 1920s, candidates for judicial office in Texas and elsewhere have been prohibited from making statements that could impugn the public perception of the candidate’s willingness to faithfully and impartially perform his judicial duties.113 However, over the past thirty years, such restrictions have been challenged as constitutionally impermissible infringements on a judicial candidate’s First Amendment rights.

In 2002, the United States Supreme Court, in Republican Party of Minnesota v. White, struck down a restriction that prohibited Minnesota candidates for judicial office from announcing their views on disputed legal and political issues.114 As one court later noted, the United States Supreme Court’s decision raised more questions than it answered about the constitutionality of restrictions on judicial campaign speech.115 Today, a significant amount of uncertainty continues to surround the permissible scope of restrictions on judicial candidate speech.

Both nationwide and in Texas, past and present restrictions on judicial campaign speech are traceable to the efforts of the American Bar Association (“ABA”). Beginning with its 1924 Canons of Judicial Ethics, and continuing with its 1972 successor, the Code of Judicial Conduct, such model legislation was adopted by most states (including Texas, in 1964), and served as a guide to judicial campaign speech for nearly fifty years.116

Two of the most of the significant provisions of the model ABA Code were its restrictions upon judicial candidates: (1) making pledges or promises of conduct in office other than the faithful and impartial performance of the duties of the office (the “Pledges or Promises Clause”); and (2) announcing their views on disputed legal or political issues (the “Announce Clause”).117

Beginning in the 1980s, candidates for judicial office nationwide began challenging these restrictions on judicial speech as violating their First Amendment rights.118 The challenges culminated in the United States Supreme Court’s decision in Republican Party of Minnesota v. White, which addressed the constitutionality of Minnesota’s Announce Clause, which was based upon the 1972 ABA Model Code.119 At the time, Texas also employed similar campaign speech restrictions.120 The question presented in White was whether the First Amendment allowed the Minnesota Supreme Court to prohibit judicial candidates from announcing their views on disputed legal and political issues.121 The Court concluded that the Announce Clause was not narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest and therefore violated the First Amendment.122 In reaching its conclusion, the majority in White ruled that the clause’s overall prohibition on announcing views on disputed legal and political issues extended beyond promising to decide a specific issue in a particular way.123 It concluded that the Announce Clause restriction would prohibit a judicial candidate from stating his views on any specific legal question within the province of the court for which he was running.124

Applying strict scrutiny, the Court next questioned whether Minnesota had a compelling interest to justify the Announce Clause.125 The state’s alleged interests were to preserve the impartiality, as well as the appearance of impartiality, of its judiciary. The Court then considered three meanings of “impartiality”: (1) the lack of bias for or against a litigant; (2) the lack of preconception in favor of or against a particular view; and (3) open-mindedness. 127 The Court concluded that the Announce Clause was not narrowly tailored to serve the first interest because it did not restrict speech for or against particular parties, but rather speech for or against particular issues.128 It further concluded that the second definition was not a compelling interest because proof that a judge lacked preconceived views on legal issues would be evidence of lack of qualification, not lack of bias.129 And it dismissed the third definition as under-inclusive, given that judges were permitted to express their views on legal issues at all times other than during campaigns.130 Based on these conclusions, the White court concluded that the Announce Clause was constitutionally unsound. 131 Since White, courts and commentators have struggled to determine whether limitations on judicial campaign speech can withstand strict scrutiny.132 In expanding the range of permissible judicial campaign speech, White “dramatically changed the landscape for judicial ethics as it relates to judicial campaigns.”133 Texas responded to White by amending the Texas Code of Judicial Conduct.134 The 2002 amendments replaced the problematic “Announce Clause”—derived from the 1972 ABA Model Code—with the current Canon 5, which provides that a judge or judicial candidate shall not

• make pledges or promises of conduct in office regarding pending or impending cases, specific classes of cases, specific classes of litigants, or specific propositions of law that would suggest to a reasonable person that the judge is predisposed to a probable decision in cases within the scope of the pledge;

• knowingly or recklessly misrepresent the identity, qualifications, present position, or other fact concerning the candidate or an opponent; or

• make a public comment about a pending or impending proceeding that may come before the judge’s court in a manner which suggests to a reasonable person the judge’s probable decision on any particular case.135

Entitled “Refraining From Inappropriate Political Activity,” Texas’s Canon 5(3) further provides that if a judge enters into an election contest for a nonjudicial office, he is required to resign from the bench. Canon 5(2) likewise bars a judge or candidate from endorsing another candidate for public office. While all such current Texas restrictions have been modified to comply with White, the constitutionality of these revised restrictions on judicial campaign speech has not yet been fully tested.

Judicial Reelection

Texas does not impose term limits on judges. However, the Texas Constitution provides that the seats of high court, intermediate appellate, and district court judges “shall become vacant” on the expiration of the term during which the incumbent reaches seventy-five years of age.136 Thus, Texas judges are not automatically turned out of office upon reaching seventy-five years of age but are instead barred from running for reelection or being appointed to another judicial position.137

As of September 2018, the justices on the Texas Supreme Court had served on the court, on average, for nine years. One justice had been on the court for over twenty-nine years, while two had been on the court for less than five.138 The justices of the intermediate courts of appeals had served on their courts for an average of nine years, with the range of experience spread fairly evenly between one and twenty-four years on the bench. The average years of experience for Texas district court judges was approximately nine years.139

Judicial Incumbent Challenges

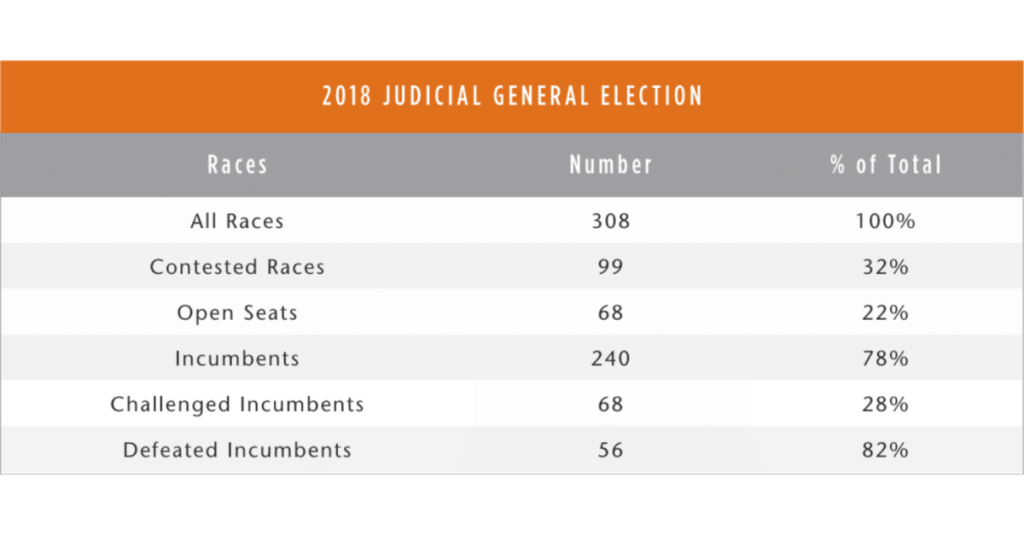

While every Texas judge who seeks to retain his office must eventually face election, in many races an incumbent judge is reelected without opposition.140 In the 2018 general election, there were a combined total of 308 races for seats on the Supreme Court, Court of Criminal Appeals, intermediate appellate courts, and district courts.141 An incumbent judge ran for reelection in seventy-eight percent of those races. Of these 240 incumbents running for reelection in the general election, twenty-eight percent had an opponent,142 as demonstrated in the chart143 below.

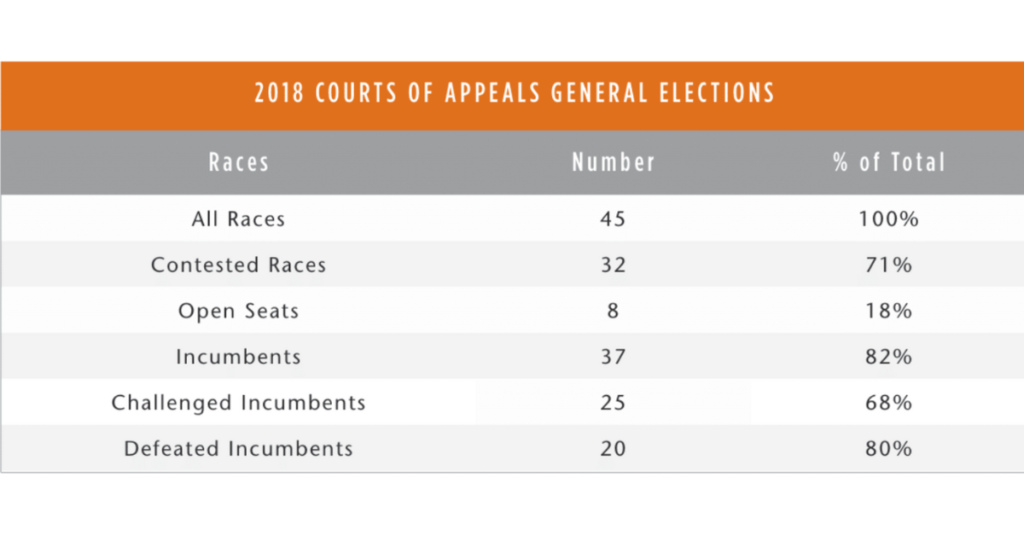

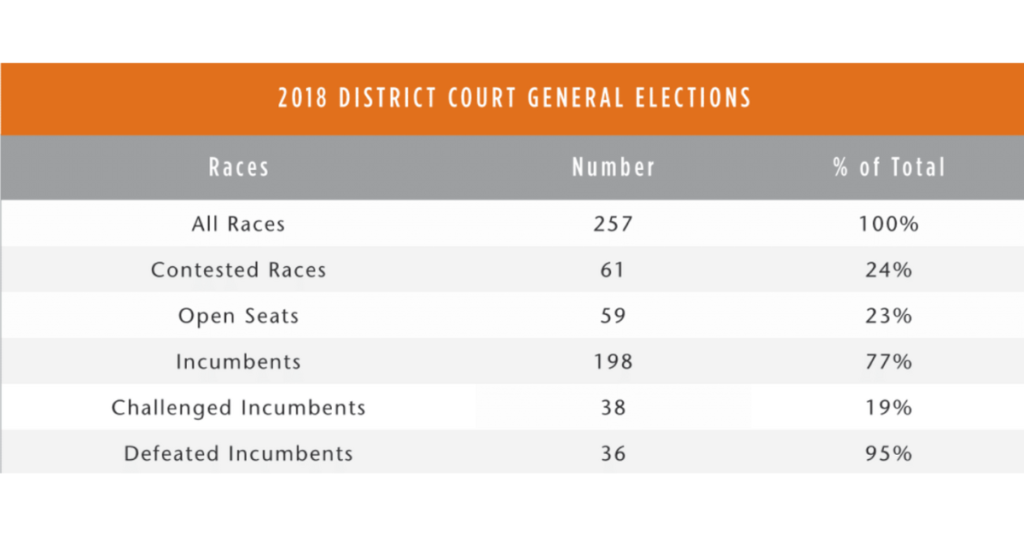

The percentage of incumbent challenges in Supreme Court and Court of Criminal Appeals races is significantly higher than the percentage in the intermediate courts of appeals and the district courts.144 In the 2018 general election, for example, all five incumbent-held seats on the ballot for the two high courts were contested. In the intermediate courts of appeals, incumbents held thirty-seven of the seats on the ballot in 2018 (out of a total of forty-five), and sixty-eight percent of those incumbents faced a contested race.145 At the district court level, 198 seats were held by incumbents (out of a total of 257), but just nineteen percent of those incumbents faced opposition in the 2018 general election.146

These November 2018 Texas judicial election results were, simultaneously, both typical and atypical. That is, in 2018, as in prior elections, a number of incumbent judges faced no opponent in either the primary or general elections. Of those incumbents who did draw an opponent, 2018 was similar to other election years in which judicial election outcomes were determined by a partisan wave. Aside from Texas’s highest courts, the great majority of challengers in 2018 were successful in unseating incumbent judges. As demonstrated in the following three charts, fully sixty-seven percent of incumbent appellate judges—and ninety-five percent of district court incumbents—facing contested elections were defeated in 2018.147

Incumbent challenges in the 2018 Republican and Democratic primary elections were relatively few in number.148 In Republican primary elections, ten of the 175 incumbents (roughly six percent) were challenged by an opponent.149 These primary challenges were most frequent in the context of Republican high court incumbents, twenty-five percent of whom faced a same-party primary opponent. The percentage of Republican incumbents challenged in intermediate appellate primary races was zero, and the percentage in district court primary races was six percent.150

In the 2018 Democratic primary elections, eleven of the sixty-nine incumbents (sixteen percent) were challenged by an opponent.151 Among the small handful of Democratic appellate incumbents, there were no primary challenges.152 At the district court level, roughly eighteen percent of Democratic incumbents faced challenges in the primary.153

Removal of Texas Judges from Office

A Texas judge may be removed from office through a variety of mechanisms. First, an Article V judge may be removed from office by the Judicial Conduct Commission for “willful or persistent violation of rules promulgated by the Supreme Court of Texas, incompetence in performing the duties of the office, willful violation of the Code of Judicial Conduct, or willful or persistent conduct that is clearly inconsistent with the proper performance of his duties or casts public discredit upon the judiciary or administration of justice.”154 In lieu of removal from office, a judge may be disciplined, censured, or suspended from office for any of the foregoing reasons and may be suspended upon being indicted by a state or federal grand jury for a felony offense or charged with a misdemeanor involving official misconduct.155

Second, a judge on the Supreme Court, a court of appeals, or a district court may be removed from office through impeachment by the Texas House of Representatives and conviction on the vote of two-thirds of the Texas Senate.156

Third, a district court judge “who is incompetent to discharge the duties of his office, or who shall be guilty of partiality, or oppression, or other official misconduct, or whose habits and conduct are such as to render him unfit to hold such office, or who shall negligently fail to perform his duties as judge; or who shall fail to execute in a reasonable measure the business in his courts, may be removed by the [Texas] Supreme Court.”157 The constitution provides that this process may be based upon “the oaths … of not less than ten lawyers, practicing in the courts held by such judge, and licensed to practice in the Supreme Court.”158 But, strictly speaking, the constitutional provision does not state that the Supreme Court may proceed to remove a judge only if ten attorneys provide sworn testimony of the judge’s incompetence or misconduct. It can be read to allow removal by the Supreme Court on its own initiative and without the participation of ten or more lawyers.

Fourth, the constitution provides that the judges of the Supreme Court, court of appeals, and district courts “shall be removed by the Governor on the address of two-thirds of each House of the Legislature, for wilful neglect of duty, incompetence, habitual drunkenness, oppression in office, or other reasonable cause which shall not be sufficient ground for impeachment.”159 It is not entirely clear how this method differs from impeachment, except that it requires a two-thirds vote in both houses rather than a two-thirds vote only in the Senate.160

This constitutional “removal by address” process is addressed in Chapter 665 of the Texas Government Code. By statute, the process applies to judges on the Supreme Court, Court of Criminal Appeals, a court of appeals, or a district court (including a criminal district court).161 The statute appears to expand the grounds for removal from those provided in the constitution by adding “breach of trust” to the list.162 The Government Code states that “incompetency” means: “(1) gross ignorance of official duties; (2) gross carelessness in the discharge of official duties; or (3) inability or unfitness to discharge promptly and properly official duties because of a serious physical or mental defect that did not exist at the time of the officer’s election.”163

Fifth, “[i]n addition to the other procedures provided by law for removal of public officers, the governor who appoints an officer may remove the officer with the advice and consent of two-thirds of the members of the Senate present.”164 If the Legislature is not in session when the Governor desires to remove an officer, the Governor must call a special session of the Senate (not, apparently, of the entire Legislature) for consideration of the proposed removal.165 The session may not exceed two days in duration.166

Sixth, in unusual circumstances, a judge may be removed through a quo warranto action. A quo warranto action may be pursued and lead to removal from office if “a person usurps, intrudes into, or unlawfully holds … an office … [or] a public officer does an act or allows an act that by law causes a forfeiture of his office.”167 Quo warranto is an action that may be pursued in district court by the Attorney General, or by a county or district attorney of the proper county.168

Seventh, the Texas Constitution provides that an Article V judicial office automatically becomes vacant on the expiration of the term during which the incumbent reaches the age of seventy-five years or such earlier age (not less than seventy years) as the Legislature prescribes by statute, unless the judge reaches the age of seventy-five years during the first four years of a six-year term, in which case the office becomes vacant on December 31 of the fourth year of the judge’s term.169 Finally, although it is not, strictly speaking, a form of removal from office, the voters

can refuse to reelect a judge under the current selection system in Texas.

PART III: JUDICIAL SELECTION PROCEDURES AMONG THE STATES

While there are two basic methods for selecting judges—election or appointment—those two conceptual methods have numerous subcategories, with the specific details of each varying greatly among the states. Academic scholarship on this topic often divides judicial selection systems into five different models: partisan election, nonpartisan election, gubernatorial appointment, legislative appointment, and the hybrid Missouri Plan appointment model.170

The election model of judicial selection breaks down into two subcategories: partisan elections, in which candidates seek election after nomination by a political party, and nonpartisan elections, in which judges run for election without reference to party labels.171

In systems that appoint judges for a term—i.e., either life or a fixed number of years— the appointments may be made by either the governor or the legislature. In rare instances, judges are appointed by the judiciary, but with such infrequency as to be excluded from the five general categories discussed in this paper.172 In the simplest terms, the distinguishing feature of the purely appointive models is that those judges never face any type of popular election, whether partisan, nonpartisan, or retention.

Finally, the Missouri Plan method for judicial selection typically involves nomination of a candidate by a judicial nominating committee173 and appointment by the governor, followed by a retention election that is usually uncontested and nonpartisan in which voters decide whether the judge should continue to hold office or the governor should appoint a new person for that office.174

These basic judicial selection models can also be further distinguished by taking into account other features, including the type and composition of commissions used to screen and nominate potential judicial candidates, senate or legislative confirmation of gubernatorial appointments, lifetime versus limited terms of appointment, and differing forms of election or reappointment after the initial selection of a judge.175

Historic Trends in Judicial Selection

The current diversity of state judicial selection models developed over the past 200 years through a series of shifts between the five general selection models, as well as incremental refinements upon those basic models. Initially, as of 1790, all of the original American states selected their judges either by gubernatorial or legislative appointment, with most states appointing judges for life terms during good behavior.176 The first major shift, often attributed to the rise of Jacksonian Democracy, started in the 1830s when states increasingly began to replace their appointive systems with partisan elections for judicial office.177 By the 1860s, partisan election was the most commonly used method of judicial selection.178 However, with the coming of the twentieth century, states increasingly adopted nonpartisan elections to replace partisan elections.179 Subsequently, many states again shifted direction in mid-century, in favor of the Missouri Plan.180

Among the evolution of judicial selection procedures, there were several pronounced trends. Appointment was the dominant method of selecting justices until the 1850s when partisan election surpassed it to become the leading method.181 Since the 1840s, legislative judicial appointment has declined at roughly the same rate as appointment by the governor has increased.182 However, for the past sixty years, the total number of states that appoint their supreme court judges has remained constant.183

Judicial selection by partisan election was first adopted in Georgia in 1812.184 By the Civil War, partisan election had become the predominant form of judicial selection.185 Indeed, up until the 1950s, every state that entered the Union after 1850 had an elected judiciary.186 In the 1920s, however, selection by partisan election began to steadily decline in prominence,187 caused in part by the rise of nonpartisan elections to select judges. Since their initial widespread adoption as part of the Progressive reforms of the 1920s, nonpartisan elections have continued to be used with greater frequency, while the popularity of partisan judicial elections has continued to wane.188

A second factor in the decline of partisan elections was the advent of the Missouri Plan. First adopted by Missouri in 1940, this model189 was adopted by over twenty states within the next three decades. Since the 1990s, however, the number of states using this model has essentially remained static.191

In sum, a historical overview of changes in judicial selection methods reveals two unmistakable trends. First, most states have tried and rejected judicial selection by partisan election.192 Of the thirty-nine states that at one time selected all of their judges by partisan election, only six states—Texas, Alabama, Illinois, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania—still do so today.193 Second, almost all states that once legislatively appointed their judges have now abandoned that model.194 Of the seventeen states that once selected judges by legislative appointment, only two—South Carolina and Virginia—continue to do so today.195

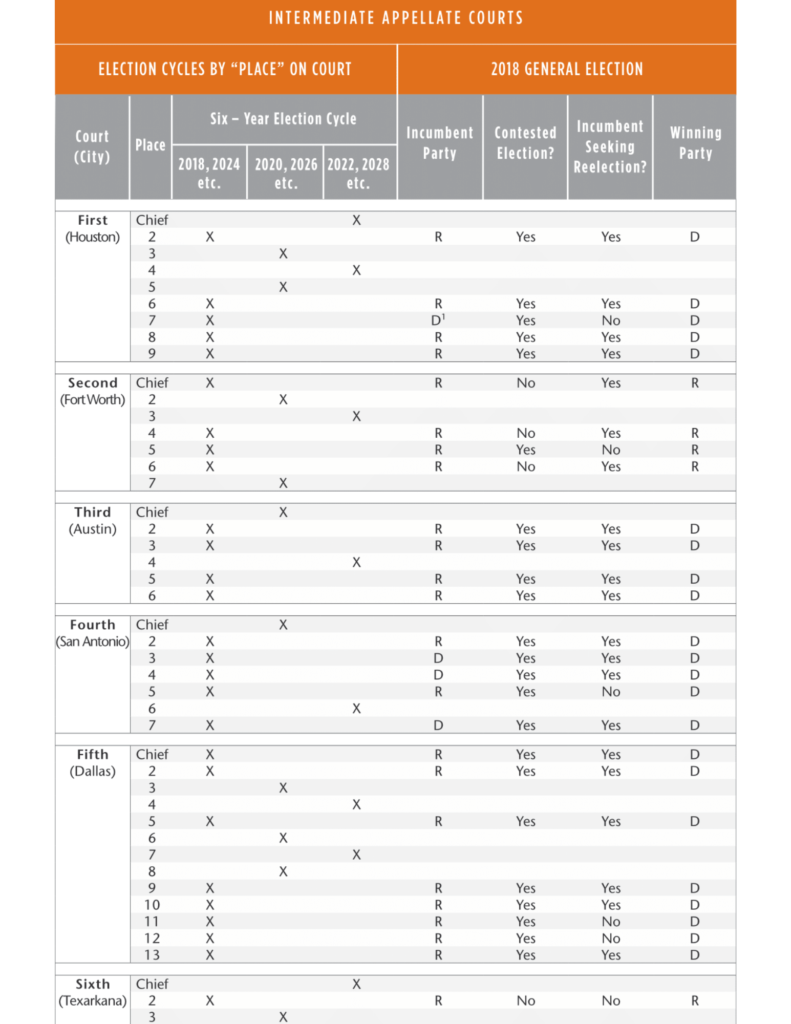

Current Methods of State Judicial Selection196

The primary focus of this paper will be on the methodology used to select judges for their first full term of office, rather than on methods used to fill the remainder of the term of a departing judge, a distinction applying only to elective states. Save for the handful of states that appoint judges to what is essentially a life term, the remaining states utilize a wide variety of approaches to retain or reject incumbent judges who later seek additional terms. In the interest of clarity, this paper largely excludes analysis of the various systems applicable to incumbents seeking additional terms.197

At the high court level, only six states—including Texas—currently select judges for first full terms by partisan election.198 Another fifteen states select high court judges for first full terms by nonpartisan election.199 Of the twelve states that appoint their high-court judges to first full terms, ten do so by gubernatorial appointment, and the other two do so by legislative appointment.200 The remaining seventeen states select high court judges for first terms via the Missouri Plan.201

Nine states do not have intermediate appellate courts.202 Of the remaining forty-one states, only six—including Texas—currently select intermediate appellate judges for first full terms by partisan elections.203 Twelve states employ nonpartisan elections. Eight states appoint their appellate judges to first full terms: five by gubernatorial appointment, two by legislative appointment, and one through appointment by the state supreme court.205 The remaining fifteen states select appellate judges for first terms pursuant to Missouri Plan appointment.206

At the trial court level, thirty-two out of fifty states select trial judges by some form of election.208 Of these, eight do so by partisan election (in nonvacancy scenarios),209 twenty do so by nonpartisan election (in nonvacancy scenarios),210 and four conduct trial-level elections only within certain counties or districts, while otherwise adhering to the Missouri Plan.211 This leaves seven states that exclusively use the Missouri Plan.212 Of the eleven remaining states that appoint trial judges to first full terms, nine do so by gubernatorial appointment, and two do so by legislative appointment.213

The preceding table summarizes the methods of judicial selection employed by states to select judges at the high court level, intermediate appellate court level, and trial court level.

As shown, there are a finite number of basic judicial selection models among the fifty states. However, as actually practiced among the fifty states, variances in the details of each selection model produce a diverse set of judicial selection methods, which can also vary among the levels of courts within one state, or occasionally among trial courts located within different areas of the same state. Moreover, states utilizing partisan or nonpartisan election systems may use one set of procedures to fill interim judicial vacancies, while employing an entirely different methodology to select judges for a first full term.

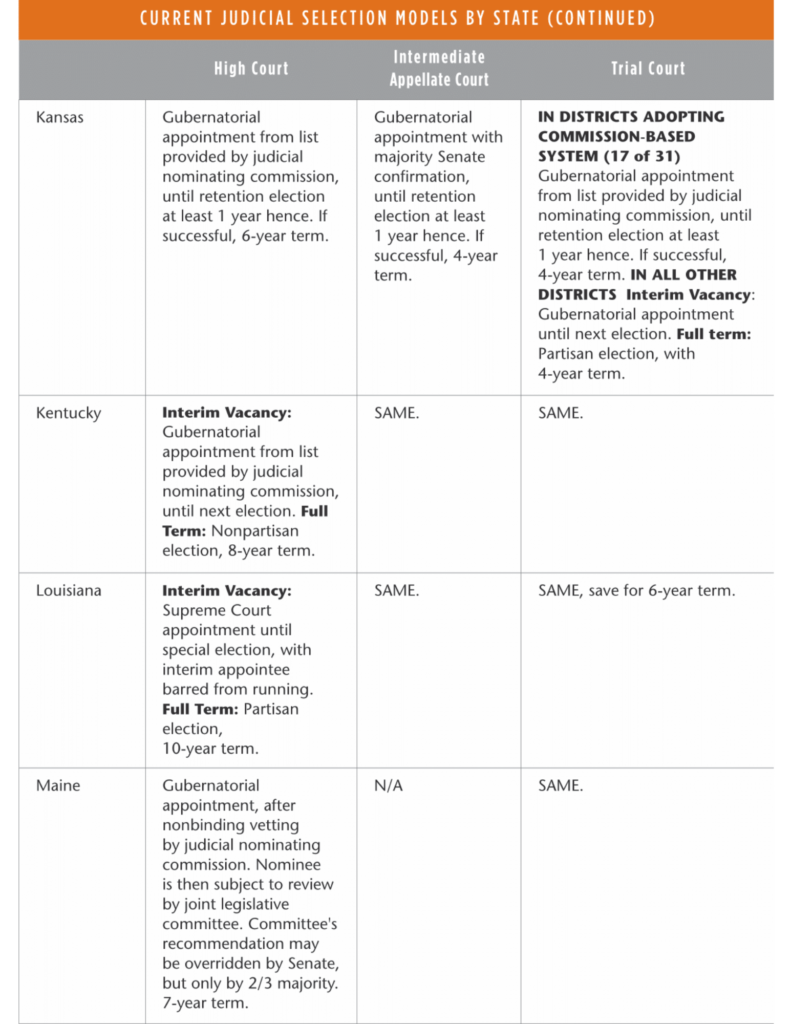

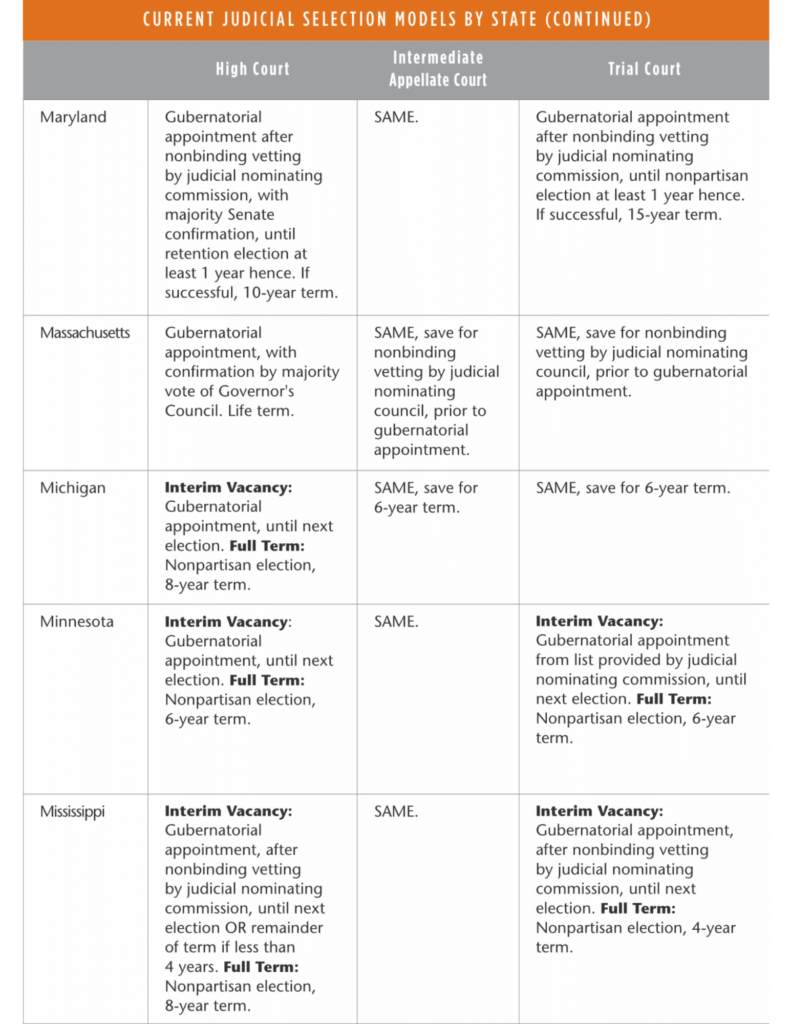

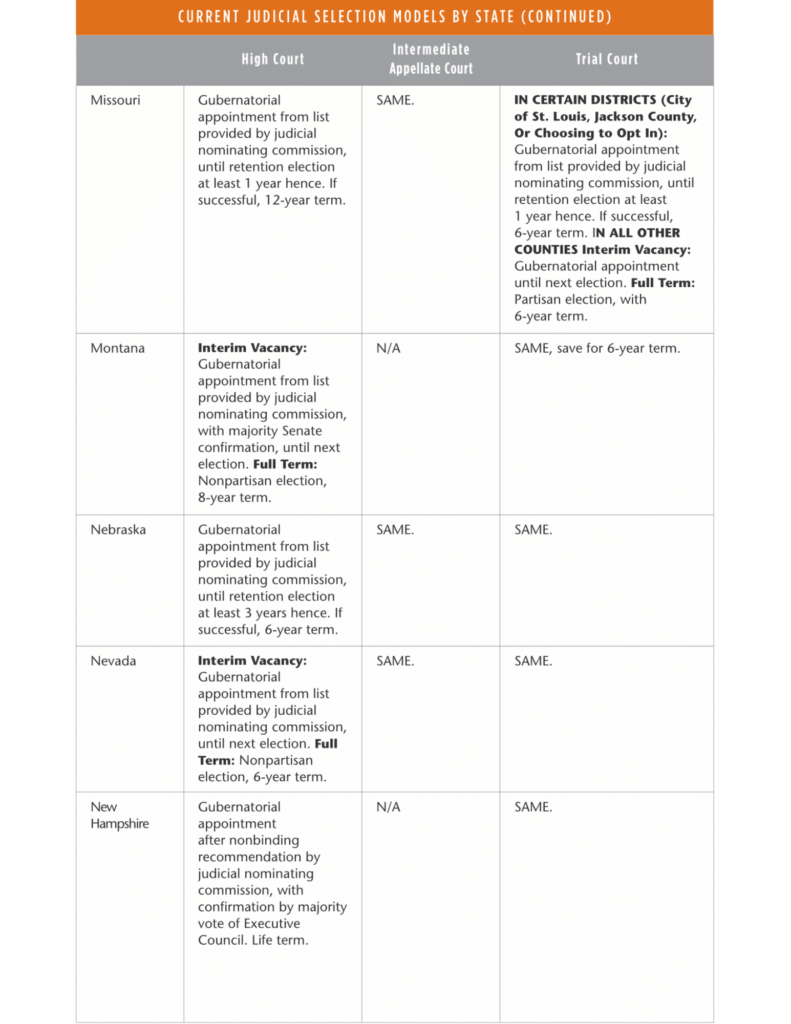

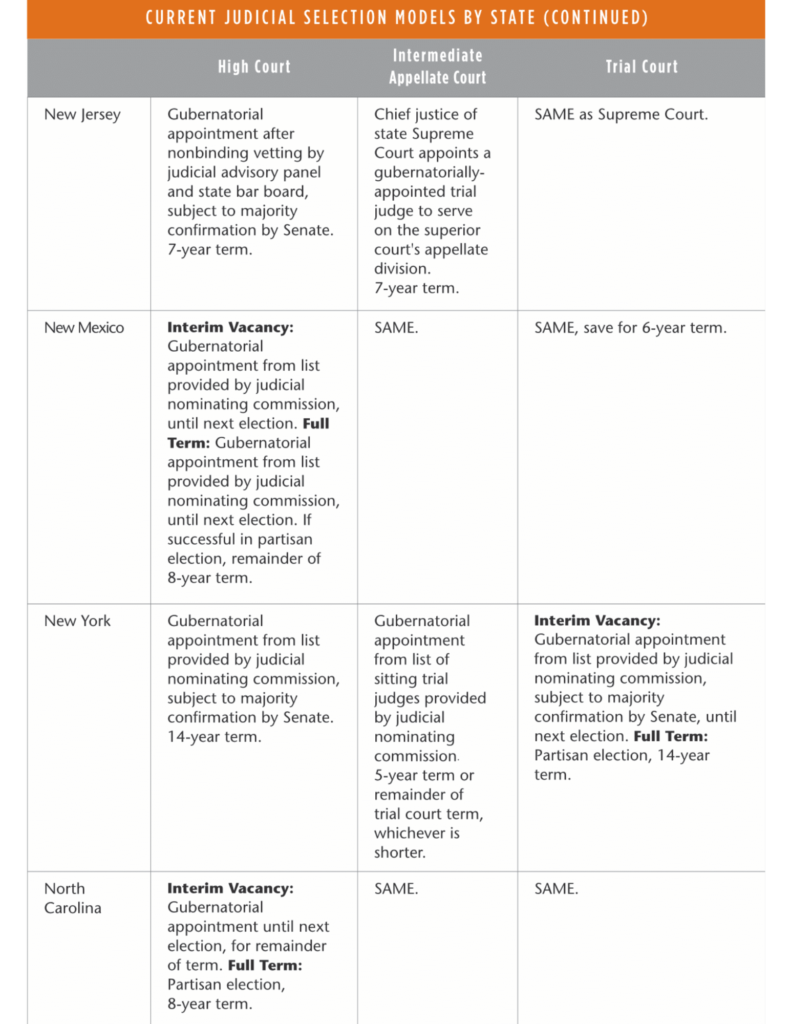

The appendix includes a table setting out how each of the fifty states has chosen to mix and match the variables set forth above, in both “vacancy” and “first term” scenarios.

Current Variations of Judicial Selection by Gubernatorial Appointment

There are ten states that extensively (although not exclusively) utilize gubernatorial appointment without an accompanying retention election to appoint judges to full terms. Again, this “first full term” qualifier is important to bear in mind because nearly all states utilize some variant of gubernatorial appointment when filling interim vacancies.215 Unlike in elective states, distinctions between interim vacancies and first full terms are irrelevant under the gubernatorial and legislative appointment models, as all vacancies are filled by full-term appointments.

The ten states utilizing gubernatorial appointments for first full-term judgeships are Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont. The procedural differences among these gubernatorial appointment states are found in the term of judicial office, the use of nominating commissions, and the requirement for confirmation of the governor’s appointee, whether by the state Senate, both houses of the Legislature, or by a panel.

In a majority of states utilizing gubernatorial appointment to fill a judicial seat for a full first term, the term is limited to a certain number of years. The terms range from six years in Vermont to fourteen years for the New York Court of Appeals. Only three states— Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island—appoint judges for what is essentially a life term (barring misbehavior) until age seventy.216 In New Jersey, a judge is first appointed to an initial seven-year term, after which he may be reappointed to a second term lasting until the age of seventy, assuming good behavior.217

Next, all states employing the gubernatorial appointment model also use nominating commissions in some fashion, with those commissions that issue binding recommendations slightly outnumbering the states utilizing nonbinding commissions. Nominating commissions are widely used across a variety of judicial selection models and serve to create a list of qualified judicial candidates from which the governor may choose, although where a commission’s recommendation is nonbinding in nature, the governor is free to request that additional candidates be supplied.218

Finally, some form of “confirmation” of a gubernatorial judicial appointment is required in all ten of the states discussed in this section. Most frequently, confirmation is performed by the state Senate or the entire Legislature. In Massachusetts and New Hampshire, confirmation authority lies with a governmental panel.

Current Variations of Judicial Selection by Legislative Appointment South Carolina and Virginia are the only states that still use legislative appointments.219 South Carolina uses a nominating commission to create a list of qualified candidates for a judicial opening from which the state’s General Assembly must select a candidate by majority vote.220 In Virginia, the names of candidates are submitted by General Assembly members to House and Senate committees that determine whether the individual is qualified for the judgeship sought.221 Following the committees’ determination of qualification, the House of Delegates and the Senate fill the vacant judgeship.222

Current Variations of Judicial Selection by Partisan Election Texas is among the six states— along with Alabama, Illinois, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania—that select all judges for first full terms using partisan election.223 There are a number of states, including Indiana, New York, and Tennessee, that make exclusive (or nearly exclusive) use of partisan elections for selecting judges solely at the trial level.

One interesting variance among these six states is the length of the term of office. At the high court level, Illinois, Louisiana, and Pennsylvania elect their justices for ten-year terms. Texas has the shortest terms of office: six years for appellate judges and four years or trial judges.

Current Variations of Judicial Selection by Nonpartisan Election A nonpartisan election model is one that generally prohibits political parties from nominating candidates for judicial office, and excludes party labels from candidates’ listings on the ballot.224 Those states that select their judges via nonpartisan election include Arkansas, Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, Ohio, Oregon, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. However, two states—Michigan and Ohio—are unique in that they use a partisan primary (Ohio) or caucus (Michigan) to select the candidates who will later run in the nonpartisan election.225

These nonpartisan-election model states utilize relatively uniform procedures, other than the length of the term for judicial office. Supreme court justices are elected to full terms between six and twelve years, with six or eight-year terms being the most prevalent. All other lower court judges are elected to terms ranging from four to eight years. Each of these states allows its governor to appoint judges to fill interim vacancies, often with the assistance of a judicial nominating commission, whether binding or nonbinding.

Two states in this group have unique judicial selection provisions. In Montana, if an incumbent is unopposed in a nonpartisan election, the judge must win a retention election to retain office.226 In Nevada, voters have the option of selecting “none of these candidates” in statewide judicial races.227

Finally, there are a number of states—including California, Florida, Oklahoma, and South Dakota—that utilize nonpartisan elections only for their trial-level courts, while employing a different model for their appellate courts.228

Current Variations of Judicial Selection by Missouri-Plan Appointment

The Missouri Plan involves an initial gubernatorial appointment from candidates supplied by a judicial nominating commission, subsequently followed by a retention election. States that employ a form of the Missouri Plan model to select judges at all levels include Alaska, Colorado, Iowa, Nebraska, Utah, and Wyoming. There are also numerous other states, such as Maryland, which selectively depart from the Missouri Plan as to certain courts (most often at the trial level). The Missouri Plan is uniformly applied in both the interim vacancy and first term scenarios, making any distinctions between interim vacancies and full first terms irrelevant.

The appointment stage begins whenever a judicial vacancy occurs. At that point, a nominating commission prepares a list of candidates qualified to fill the vacancy. Such listing is binding in all of the aforementioned states, except Maryland. The governor then appoints a person from that list to fill the vacancy. In most states that follow this method, there is no legislative oversight of the appointment process. In Maryland and Utah, however, the governor’s appointment is subject to senate confirmation.

At this point in the process, the operation of the Missouri Plan is often identical to that of the gubernatorial appointment model, with the two models differing only when the newly appointed judge’s initial term has concluded. At that point, a judge seated via the gubernatorial appointment model will (if not in a life-term state) face reappointment no earlier than four years later, but not reelection. A judge appointed pursuant to the Missouri Plan will face a retention election after an initial term of between one to three years on the bench.229 If the judge wins the election, the judge is entitled to hold office for a full term.230 Among the Missouri Plan states, full terms for supreme court seats range from six to twelve years, for intermediate courts of appeals six to eight years, and for trial courts six to fifteen years. At the end of each full term, a judge then faces another retention election. If the judge loses a retention election, the seat becomes vacant, and the selection process starts over again.

Finally, there are numerous states that apply the Missouri Plan in their higher courts but utilize alternate methods at the trial court level. These states include Arizona, California, Florida, Indiana, Kansas, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Tennessee.231

Justice O’Connor Judicial Selection Plan Both before and after serving on the United States Supreme Court, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was an outspoken opponent of contested judicial elections.232 Following her 2006 retirement from the bench, O’Connor began to work closely with the Denver-based Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System. Her collaboration with the Institute resulted in the 2014 publication of the O’Connor Judicial Selection Plan (“O’Connor Plan”).233 O’Connor stated that she was “distressed to see persistent efforts in some states to politicize the bench and the role of our judges” and described the plan as a step toward “developing systems that prioritize the qualifications and impartiality of judges, while still building in tools for accountability through an informed election process.”234 The O’Connor Plan notes that “[w]e do not offer it as perfect; no selection system is.”235

The O’Connor Plan adopts the primary elements of the Missouri Plan—including gubernatorial appointment, judicial nominating committees, and no-opponent retention elections—while nonetheless suggesting numerous modifications intended to improve upon the Missouri Plan. Only three states—Alaska, Colorado, and Utah—are already fully compliant with all four elements of the O’Connor Plan.236

As to the first element, judicial nominating commissions, some of the plan’s notable features include requirements that commissions be constitutionally authorized (rather than created via revocable executive orders), that commission members be appointed by multiple authorities and represent a broad range of societal interests, and that a majority of commission members be nonlawyers.237

The O’Connor Plan’s second element limits the number of nominees presented to the governor by the nominating committee and bars the governor from departing from the committee’s list.238 Moreover, in order to prevent judicial seats from going unfilled for political purposes, the plan provides for a default appointment mechanism, in the event the governor fails to take prompt action.239

The plan’s third element involves a method for extensive judicial performance evaluation, whereby freestanding, statutorily created commissions (populated in large part by nonlawyers) would evaluate sitting judges based on criteria focusing on sound decision-making processes, rather than the outcome of any particular case.240 Such evaluations would then be regularly disseminated to assist voters in connection with the plan’s final element: retention elections.241 Seeking to strike a balance between judicial independence and accountability, the plan stresses that retention elections should represent a yes/no referendum on an incumbent judge’s performance rendered on the basis of the data made available to the voting public via the evaluation process and be conducted without fundraising, political efforts, or speech-making by the incumbent.242

Use of Nominating Commissions in State Judicial Selection

The broad majority of states use one or more judicial nominating commissions in some manner when selecting judges.243 Some authorities place the total number of states employing such commissions at thirty-six and others at thirty-eight, a disparity reflecting the myriad forms and roles such commissions assume.244 Texas is among the minority of states that does not utilize a nominating commission in their judicial selection system. Among those majority states that do employ commissions, there are numerous differences concerning the number and composition of commissions, their methods of selecting members, and requirements regarding the commissions’ geographic and political makeup. However, certain generalizations may be made regarding these commissions.

Nominating commissions generally find, screen, evaluate, and nominate candidates for appointment to judicial office. In states that employ the Missouri Plan, commissions typically submit a list of potential nominees to the governor for each vacancy, and the governor usually must appoint one of those nominees.245 However, in a significant number of states, the judicial commission’s recommendation is nonbinding, and the governor is not required to choose from among the offered list of candidates.246 Even among states that elect judges, nominating commissions are often used in filling interim vacancies.247 Finally, several states, such as Alabama, Arizona, Indiana, Kansas, and Missouri, use nominating commissions to select judges only in certain counties or districts—usually urban—while not utilizing them in less-populated areas.248

There is also a great degree of disparity among the states regarding how judicial nominating commissions are established: some by executive order, some by statute, and others by constitutional amendment.249 While some states utilize a single nominating commission for all of their courts, other states have created multiple county-level commissions to supply trial court nominees in each of the counties.250 Moreover, a state may choose to utilize a nominating commission for one level of courts, but not another.251 Minnesota, for example, utilizes a commission for its trial courts, but not its appellate courts.252

Nominating Commissions Among the States

Missouri Plan States A significant number of states—including Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, and Wyoming—utilize one or more judicial nominating commissions in conjunction with the Missouri Plan, wherein the initial gubernatorial appointment is followed by a retention election.253 In fact, use of judicial nominating commissions is essentially synonymous with the Missouri Plan, subject only to the caveat that two of these states— California and Maryland—employ commissions whose candidate lists are not binding on their respective governors.

Gubernatorial Appointment States In a number of primarily eastern states—including Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, NewJersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont—at least some judges are appointed (for either life, or a term of years) by the Governor, almost always from a list provided by a judicial nominating commission and usually subject to confirmation by the Legislature or Senate.254 In at least some of these appointive states—including Massachusetts, Maine, and New Jersey—the list of nominees submitted to the Governor is not binding, and he or she may appoint someone not considered by the commission.255 In appointing justices to Massachusetts’s highest court, however, the governor forgoes the assistance of any formal nominating commission.

What these states have in common with Missouri Plan states is the involvement of judicial nominating commissions. One notable difference, however, is that in gubernatorial appointment states, the commissions tend to be established via executive order, rather than by statute.256 The major difference between gubernatorial-appointment and Missouri Plan states is that the appointed judges do not stand for retention elections in the gubernatorial-appointment states.

Traditional Election States Among the states that exclusively utilize elections (whether partisan or nonpartisan) to select judges for their first full terms, there is obviously no role for judicial nominating committees. Nonetheless—and excluding the Missouri Plan states—a sizeable number of states that otherwise select judges via popular election use a combination of nominating commissions and gubernatorial appointments when filling interim vacancies for at least some courts. These states include Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, New York, North Dakota, West Virginia and Wisconsin.257 In several of these states, senate or legislative confirmation may also be required.258 And in several of these elective states—including Georgia, Mississippi, and Wisconsin—the list of nominees submitted to the governor is not binding, and he or she may appoint someone not considered by the commission.259 In North Dakota, the Governor may likewise choose not to appoint from the commission’s list, but then must either request a new list or call a special election to fill the vacancy.260 While these nominating committees are rare among those six states that exclusively elect full-term justices via partisan elections (the group that includes Texas), Alabama does make use of nominating commissions on a limited basis at the county level.

Legislative Appointment States South Carolina and Virginia are unique in that they select judges by legislative appointment.261 In South Carolina, the General Assembly appoints judges from nominees submitted by its Judicial Merit Selection Commission,262 a ten-member committee selected by legislative leaders and having at least six members chosen from the General Assembly.263

In Virginia, the names of candidates are submitted by General Assembly members to the House and Senate Committees for Courts of Justice, and these committees determine whether each individual is qualified for the judgeship sought.264 Following the committees’ determination of qualification, the House of Delegates and the Senate then vote separately, and the candidate receiving the most votes in each house is elected to the vacant judgeship or new seat.265

Number of Nominating Commissions Per State Of those states that use some form of nominating commission, more than one-half use only a single commission.266 Of those remaining states utilizing multiple commissions, the total number of nominating commissions ranges from a low of three in Arizona to fifty-seven in Kentucky and 114 in Iowa.267

Of the states that use nominating commissions at least partly on the basis of executive order, only Maryland and New York use more than one commission.268 Many single-commission states are largely rural or relatively small, including Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming.269

Among those states utilizing multiple nominating commissions, a given commission’s jurisdiction typically covers an appellate or trial court district. One relatively common structure utilizes one statewide commission for supreme and intermediate appellate courts and a second set of local commissions—one for each of a state’s judicial districts—to handle trial courts. States that have adopted this structure include Colorado, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, New Mexico, and Utah.270 A similar arrangement, used by Florida and Nebraska, involves separate nominating commissions for each intermediate appellate district, in addition to those for trial court districts.271

Number of Commissioners It is difficult to generalize concerning the number of commissioners that serve on nominating commissions among the states, especially given that in certain states, such as Indiana, appellate level nominating commissions may differ in size from trial-level commissions.272 Most often, commission membership ranges between seven to nine members.273 The remaining commissions range from as few as five members in Alabama to as many as twenty-one in Massachusetts.274

The above numbers represent only those “full time” commissioners expected to participate in all committee decisions. However, a few states utilize alternate structures in which a core group of commissioners is supplemented by additional members from the district or circuit in which a particular vacancy occurs. Minnesota, for example, has a forty-nine member commission, but only nine at-large members uniformly participate in meetings and deliberations on every vacancy.275 Four additional members of the commission are selected from each of the state’s ten judicial districts, with each four-member bloc participating only when a vacancy occurs within its specific district.276

Selection of Commissioners Among those states that utilize judicial nominating commissions, differing methods of selecting commission members have developed. The most prevalent

method involves a hybrid system, in that the attorney members are either appointed or elected by the state bar association, and the nonattorney members are gubernatorially appointed, with the state supreme court chief justice often serving as the ex officio chair. Both attorney and nonattorney members may also be confirmed by the Legislature or Senate. Examples of states utilizing this method for at least some commissions include Alaska, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, and Wyoming.277

Other states provide for the selection of at least some commission members by appointment but disperse that appointive power among various state officials. In Colorado, attorney members of its nominating commission are appointed by majority action of the governor, the attorney general, and the chief justice, with the governor retaining power to appoint all other members.278 In Connecticut, Hawaii, New Mexico, and New York, the selection process includes appointment of some commissioners by certain members of those states’ legislatures. 279 These appointing authorities may include the president of the senate, the speaker of the house, and the majority and minority leaders of either or both houses.280 Commissions in Hawaii, New Mexico, and New York also have additional members appointed by their chief justices.281