Intermediate Appellate Courts in Texas: A System Needing Structural Repair

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION

II. TEXAS’S INTERMEDIATE APPELLATE COURTS

A. History of Court Districts and Judgeships

B. Districts’ Populations and Caseloads

C. Docket Equalization

D. Operations and Productivity

- Working in Panels

- Overall Productivity

- Increases in Productivity Due to Technology

- Increases in Productivity Due to Staffing Adjustments

- Increases in Productivity Through Use of Visiting Justices

- Productivity of Clerks’ Offices

E. Court Budgets

F. Overlapping Appellate Court Districts and Bisecting Trial Court Districts

G. Uneven Distribution of Justices in Election Cycles

III. ADMINISTRATION OF THE JUDICIARY

IV. COMPARISON TO OTHER JURISDICTIONS

V. RECOMMENDATIONS

A. Commentators Have Recommended Changes for Decades

B. Merging or Redistricting the Intermediate Appellate Courts

1. Benefits of Creating New Districts

a. Reduce conflicting decisions

b. Eliminate problems from overlapping and bisecting districts

c. Reduce transfer of cases

d. Reduce “small court” problems

e. Achieve cost savings

2. Constitutional Considerations and the Voting Rights Act

3. Possible Court Districting Plans

a. Methodology

b. Criteria and assumptions underlying plans

c. Schenck’s five-district court-merger plan

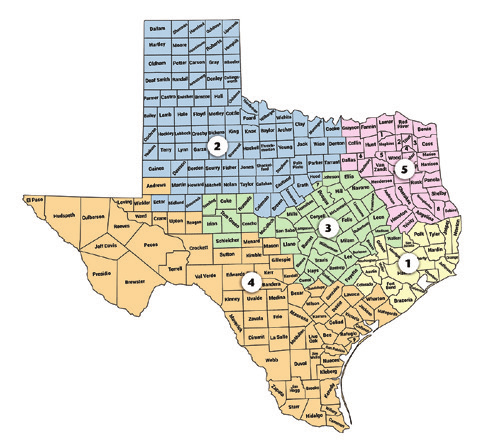

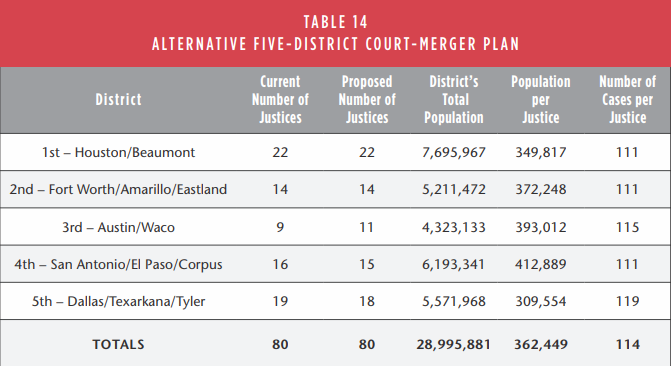

d. Alternative five-district court-merger plan

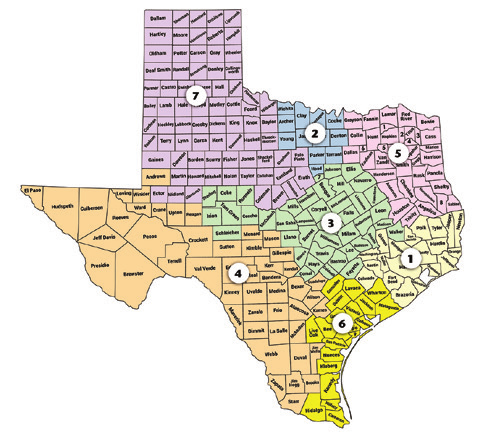

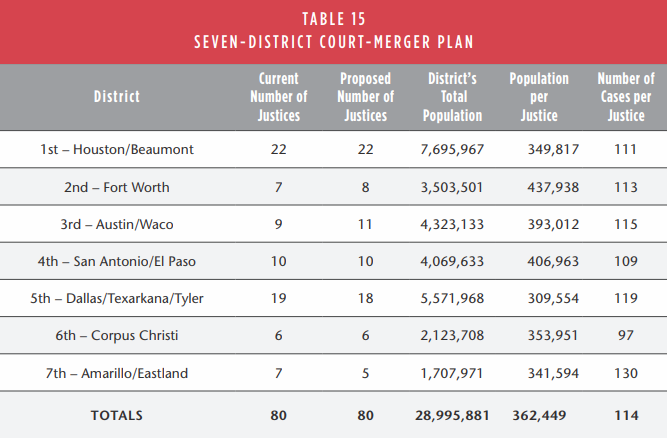

e. Seven-district court-merger plan

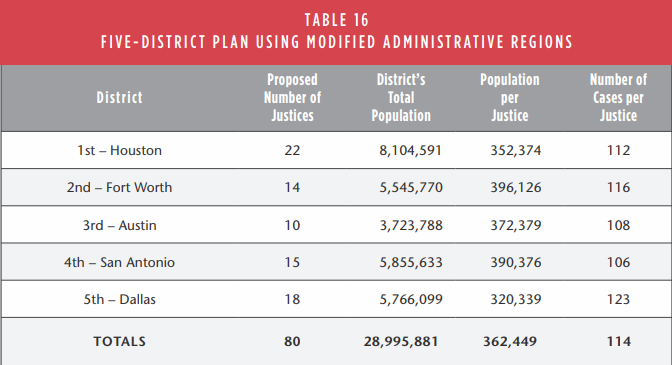

f. Five-district plan based on administrative districts

C. Transfer Administrative Authority to Intermediate Appellate Courts

D. Reallocate Seats in Election Cycles

VI. CONCLUSION

INTRODUCTION

Texas has fourteen intermediate appellate courts. The structure of Texas’s intermediate appellate court districts is fraught with defects that create conflicts among the courts, unnecessary burdens on Texas’s two high courts, inefficiencies, and confusion.

One of the most acute defects is that the intermediate appellate courts have overlapping geographic territories. In fact, the geographic and substantive jurisdictions of each of the two Houston-based appellate courts are identical, while three other courts located in northeast Texas have overlapping boundaries. As a result, multiple Texas counties sit in two appellate court districts. No other state has appellate courts with overlapping boundaries. The trial judges in the overlapped counties answer to two different appellate courts. Consequently, in pretrial proceedings and during trial, these judges do not know which appellate court will hear an appeal of the case they are adjudicating. Therefore, they have no way to know which appellate court’s precedent to follow when ruling on motions and objections. And, because there is no system for allocating appeals between the competing appellate courts from the overlapped counties in northeast Texas, litigants in those counties often race to perfect an appeal. They do this because the first-filed notice of appeal establishes that appellate court’s “dominant jurisdiction” over the case, to the exclusion of the competing court of appeals.

Adding to the disorganization, appellate court district lines bisect multi-county trial court districts in almost every area of the state. The trial judges in these districts answer to two, three, or even four different courts of appeals. As these judges “ride their circuits,” hearing cases in the different counties located within their districts, they are required to know and correctly apply appellate court precedent that is applicable to the specific county in which trial is being held. Given the breadth of issues presented to these trial courts on a daily basis, the task is practically impossible.

Texas has the largest number of intermediate appellate courts in the nation—more than the federal system or any other state. The number of justices serving on each of the courts ranges from three to thirteen. The number of cases filed each year in these courts also varies significantly, requiring constant transfer of cases between courts to equalize their dockets. These transfers are unpopular and create their own problems. Famously, one case that was appealed three times was heard by three different intermediate appellate courts in Texas.

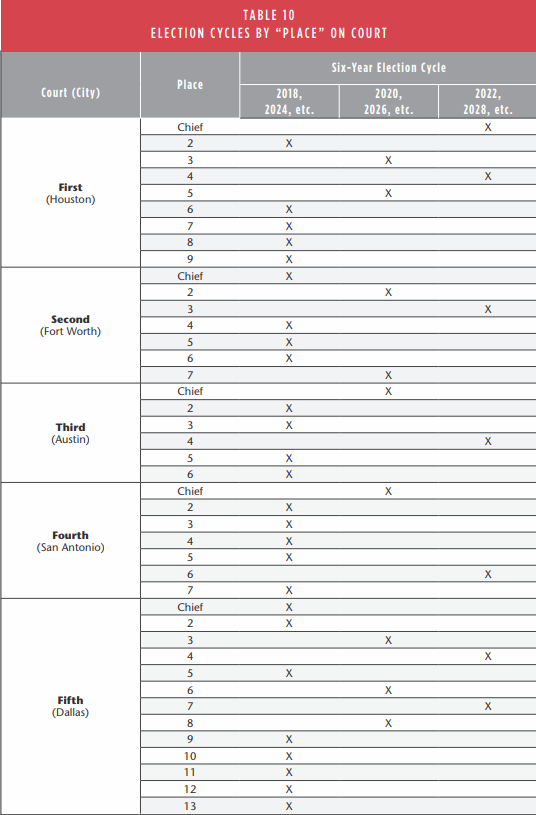

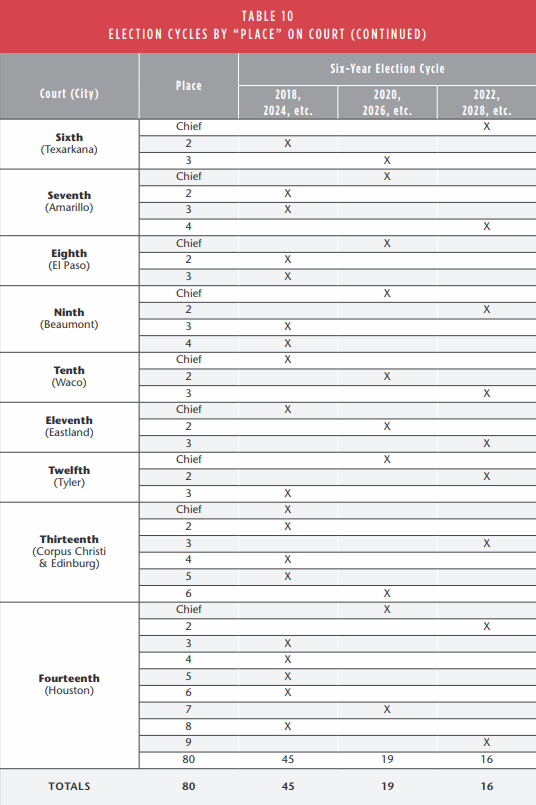

Another unusual aspect of Texas’s appellate court system is the allocation of justices in election cycles. Each of the eighty justices on these courts must stand for election every six years. Ideally, about one-third of the judiciary would stand for election in each cycle. Instead, forty-five of the seats appear on the ballot in one election cycle, while nineteen are on the ballot in the next cycle, and sixteen are on the ballot in the third cycle. This means that more than half the intermediate appellate court judiciary may be devoting time to campaigning for reelection the same year, thus taking away from their work on the courts. When a significant number of these justices are replaced by the voters in a single election—as happens from time to time in partisan sweeps that have nothing to do with the actual qualifications of the judicial candidates—the courts of appeals are suddenly piloted by new, often inexperienced justices who must deal with inherited caseloads that accumulated during the campaign and will continue to grow while the new justices learn the job.

There is nothing new about these problems. In 2007, Texans for Lawsuit Reform Foundation joined a chorus of voices that had been advocating for structural reform of the courts for decades. The Foundation published The Texas Judicial System, Recommendations for Reform,[1] outlining many of the problems discussed at length in this paper. This paper supplements and expands Recommendations for Reform in regard to Texas’s intermediate appellate court system, providing a detailed history of the development of Texas’s intermediate appellate courts, followed by a description of the inefficiencies and defects within the existing system and a comparison to other jurisdictions. This paper concludes with recommendations designed to repair the most obvious defects in order to achieve a more efficient and consistent structure that will benefit litigants, the judicial system, and all Texans.

II. Texas’s Intermediate Appellate Courts

A. History of Court Districts and Judgeships[2]

In 1876, Texans adopted a constitution that remains in effect today, although it has been amended hundreds of times over the fourteen decades it has been in place.[3] Article V, Section 1 of the 1876 Constitution vested judicial power in “one Supreme Court, in a Court of Appeals, in District Courts, in County Courts, in Commissioners Courts, in Courts of Justices of the Peace, and in such other courts as may be provided by law.”[4] The three-justice Supreme Court was given jurisdiction to hear appeals of judgments and interlocutory orders in civil cases emanating from the district courts.[5] A three-justice Court of Appeals was given jurisdiction of all criminal appeals and those civil appeals emanating from the county courts.[6] There was no intermediate appellate court for either civil or criminal cases.

The Texas Legislature proposed, and voters passed, an amendment to the Texas Constitution in 1891 that rewrote the judiciary article, vesting judicial power in, among others, “Courts of Appeals” and “a Court of Criminal Appeals.”[7] The revised judiciary article required the Legislature to divide the state into “not less than two nor more than three supreme judicial districts, and thereafter into such additional districts as the increase of population and business may require, and . . . establish a Court of Civil Appeals in each of said districts.”[8] The Constitution, as amended, provided that these new intermediate appellate courts were to have three justices each, with jurisdiction to hear appeals in civil cases.[9] Appeals in criminal cases were sent directly to the Court of Criminal Appeals, which had been called the “Court of Appeals” under the 1876 Constitution.[10]

Importantly, as will be discussed in the following paragraphs, the constitutional provision limiting each intermediate appellate court to three justices (which was not changed until 1978) forced the Legislature to create new appellate courts, rather than add justices to the existing courts, to meet the demands placed on the judicial system by the state’s ever-increasing population.

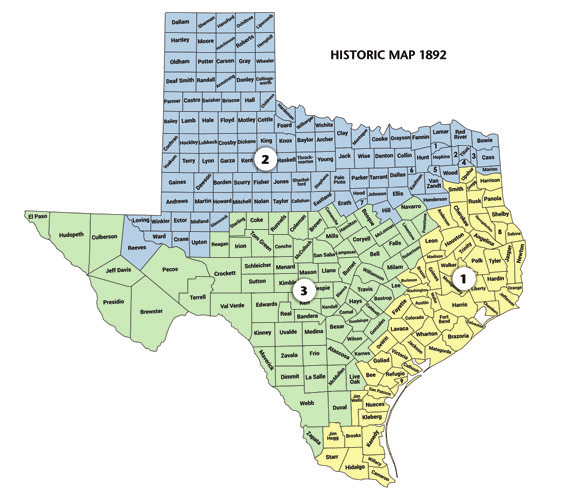

In 1892, the Legislature gave life to Texas’s intermediate courts of appeals, passing statutes providing that “the courts of civil appeals now or hereafter organized in this state shall consist of a chief justice and two associate justices” who were to be elected by the qualified voters of their districts.[11] The courts were given appellate jurisdiction of civil matters having more than $100 in controversy, boundary disputes, slander cases, divorce cases, and contested elections.[12] Their judgments were final as to the facts of the appealed case.[13] Because court-made rules of procedure did not yet exist, the procedures to be used by the courts to receive, hear, and decide appeals also were spelled out in the 1892 statutes.[14] The Legislature “divided [the state] into three supreme judicial districts for the purpose of constituting and organizing the courts of civil appeals therein respectively.”[15] The first court of civil appeals was to sit in Galveston, the second in Fort Worth, and the third in Austin.[16] Barely a year later, in 1893, the Legislature created the fourth and fifth courts of civil appeals, which were placed in San Antonio and Dallas.[17] Austin was the seat of government, and the other four cities in which courts were situated in 1893 were Texas’s major population centers (along with Houston).[18]

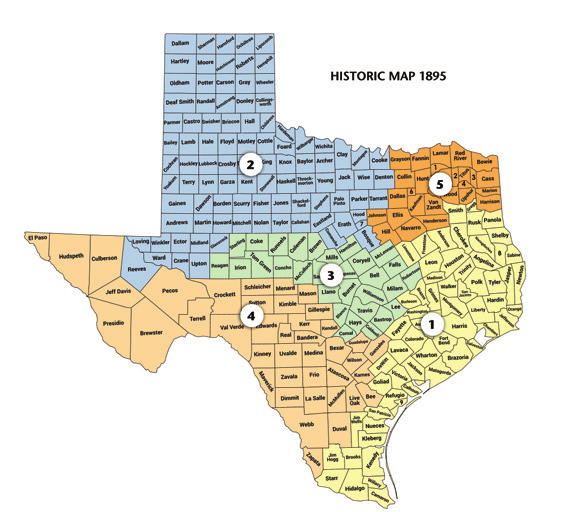

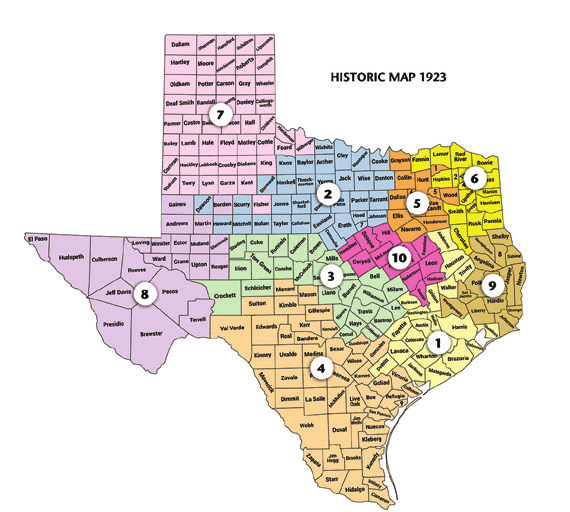

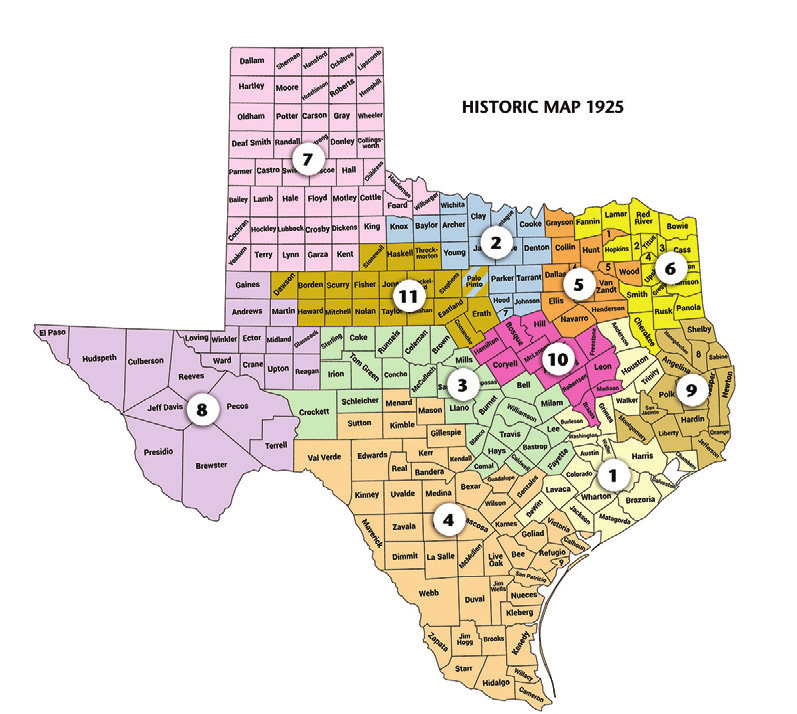

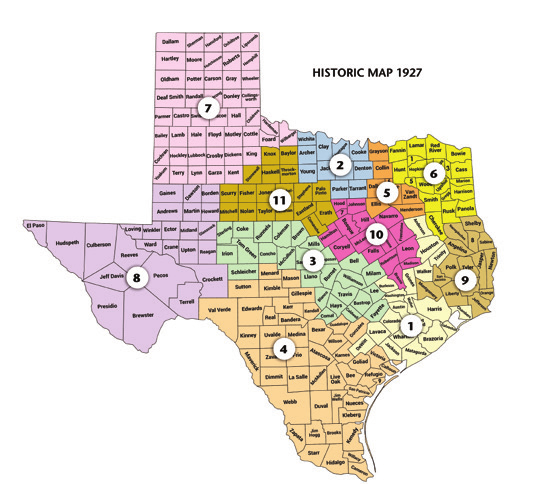

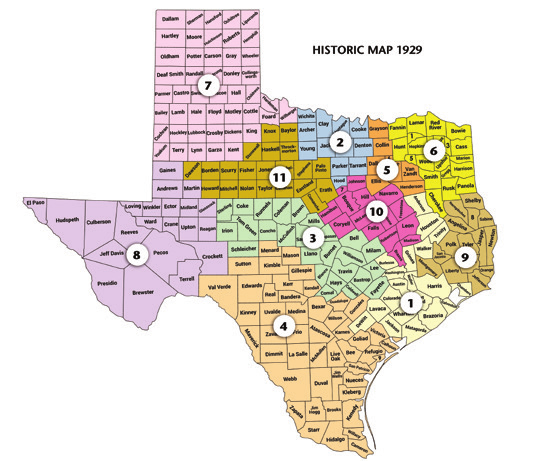

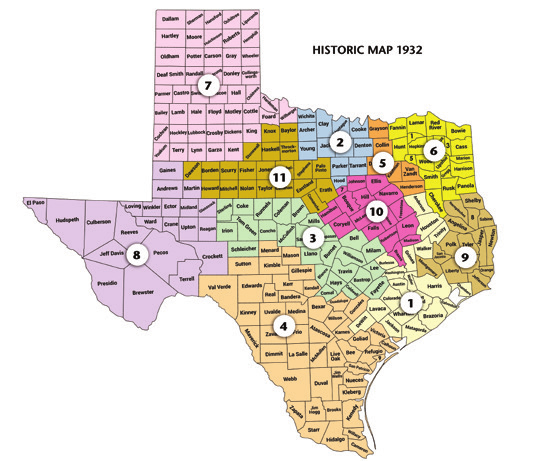

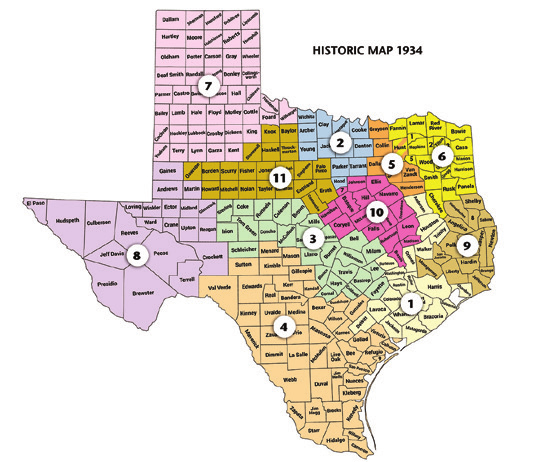

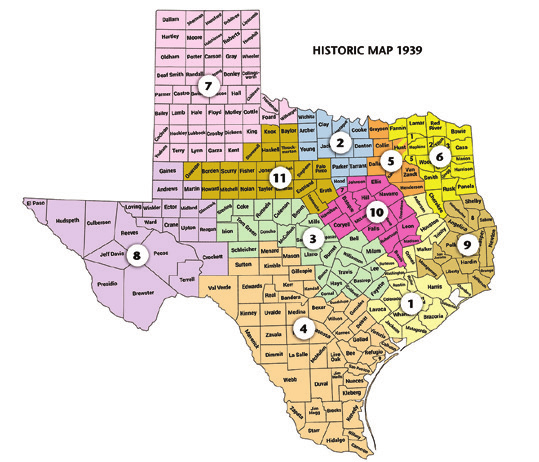

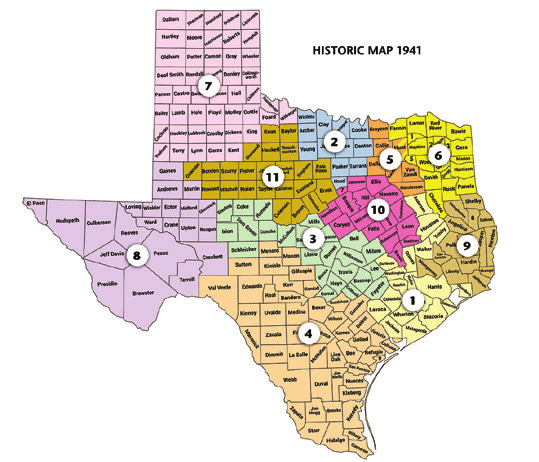

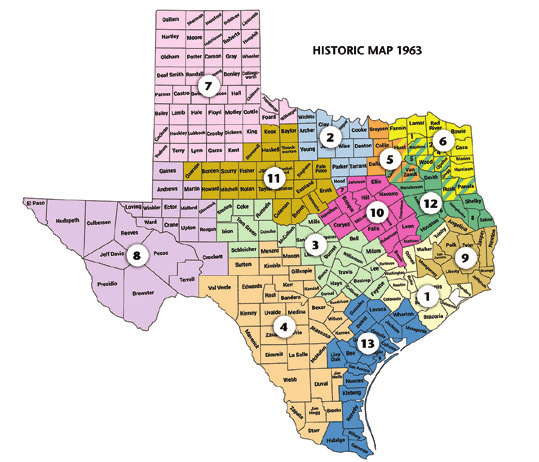

Although no legislative enactment has been found that amended the 1893 legislation allocating counties to the courts of appeals’ districts, the 1895 codification of Texas law differs in its allocation of the counties from the 1893 legislation, as shown on the preceding and following maps.[19]

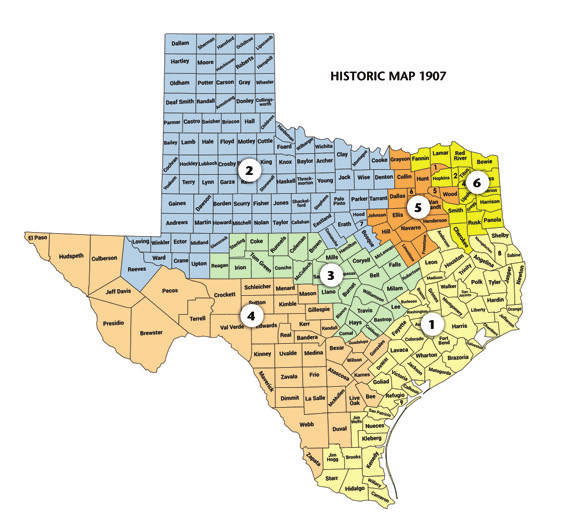

As caseloads blossomed with increases in Texas’s population, these three-justice appellate courts could not keep up with the workload, thus necessitating the creation of more and more intermediate appellate courts.[20] In 1907, the Legislature created the sixth court, which it placed in Texarkana.[21]

The placement of the court in Texarkana was not illogical. Texarkana (1910 population of 9,790[22]) and Tyler (1910 population of 10,400) were the largest cities in the area, and, therefore, one of the two cities would be a logical choice for locating the sixth court to serve the inhabitants of northeast Texas. Of course, it also would have been logical to increase the number of justices on the Dallas court to handle the increased caseload. Texarkana is only 180 miles from Dallas, which is a modest distance compared to the distances many lawyers would have traveled to argue cases in the appellate courts at the time. The problem with expanding the Dallas court was that the Texas Constitution allowed only three justices to serve on an intermediate appellate court,[23] and the number could not be increased by statute. The only way to relieve the Dallas court’s caseload was to create a new court.

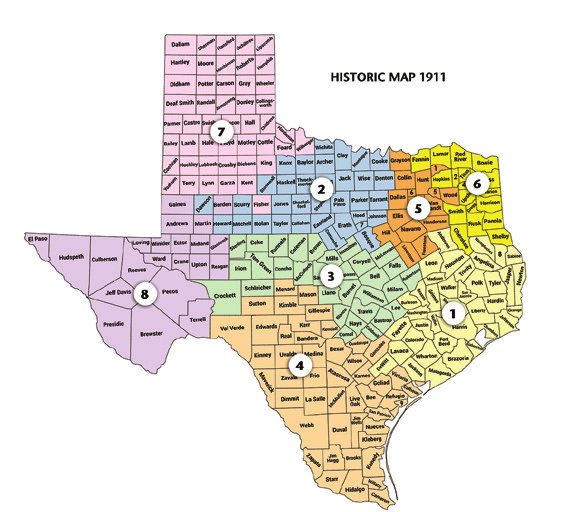

In 1911, the seventh and eighth courts were created and placed in Amarillo and El Paso, respectively.[24] There were no courts in the western half of the state before 1911, and so the placement of a court in the Panhandle and a court in far west Texas was sensible given the great distances litigants from those areas would have been forced to travel in the pre-automobile era. Amarillo was the only city of any size in the Panhandle (1910 population of 9,957), and El Paso was one of the largest cities in the state (1910 population of 39,279).

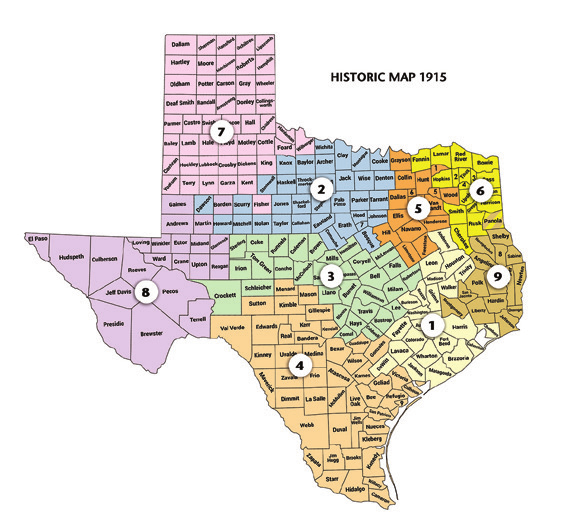

The ninth court was created in 1915 and placed in Beaumont.[25] In 1901, the famous Spindletop oil field was discovered, making Beaumont a boomtown.[26] The 1920 population of Beaumont was 40,422, having grown by 20,000 residents since 1910. Placing a court of appeals in a large and growing town would have made sense, but it also would have made sense to increase the number of justices on the Galveston court of appeals, had the Texas Constitution allowed it. Whether intentional or the result of a mistake, the 1915 legislation left Panola County in the Texarkana court’s district, but it was also included in the Beaumont court’s district.[27] This is the first instance of overlapping appellate court districts in Texas.

The tenth court, sited in Waco, was created in 1923.[28] Waco (1920 population of 26,425) was the largest city between Dallas/Fort Worth and Austin. If a court was needed in central Texas, Waco was perhaps the logical place to put it; but, again, increasing the size of the Austin court (about 100 miles south) or the Fort Worth court (about 90 miles north) would have addressed the caseload problem just as well. The 1923 distribution of counties resolved the first instance of overlapping districts, removing Panola County from the Beaumont court’s district and leaving it in the Texarkana court’s district.

The eleventh court was placed in Eastland in 1925.[29] Location of a court in Eastland is not easily explained. Eastland’s population in 1910 was 855. It enjoyed a brief oil boom between 1910 and 1920, growing to 9,368 residents in 1920. But its population fell back to 4,648 by 1930, and the population has remained approximately the same ever since. Eastland was not far from either Fort Worth or Waco (about 95 and 130 miles, respectively), both of which already were hosting intermediate appellate courts. Abilene would appear to have been a better site for a new central-west court, if one was needed. Abilene was a larger city at the time (1920 population of 10,274 and 1930 population of 23,175), closer to the other population centers in the region (Midland and San Angelo). But for reasons that are not apparent on the face of old legislative documents, Eastland was awarded a court of appeals in 1925. It is still there today, in a county that has twenty residents per square mile.[30]

The 1925 allocation of counties created the second instance of overlapping appellate court districts. Palo Pinto County—whether intentionally or inadvertently—was put in both the Fort Worth and Eastland courts’ districts.

From 1927 to 1941, the Legislature altered the distribution of counties in the eleven appellate court districts several times.

- In 1927, the Legislature fixed the Palo Pinto County overlap by removing the county from the Fort Worth court’s district. It also moved fourteen other counties between appellate court districts.[31]

- In 1929, the Legislature moved Borden, Dawson, and Howard Counties from the El Paso court’s district into the Eastland court’s district, and Hood County was relocated to the Waco court’s district from the Fort Worth court’s district.[32]

- In 1932, Ellis County was removed from the Dallas court’s district and put into the Waco court’s district.[33]

- In 1934, the Legislature returned Hunt County to the Dallas court’s district, but did not remove it from the Texarkana court’s district. Instead, it included a proviso that Hunt County judgments signed in the first half of the calendar year should be taken to the Texarkana court, while judgments signed in the second half of the year should be taken to the Dallas court.[34] This created the third instance of overlapping districts, which was clearly intentional.

- In 1939, the Legislature moved DeWitt County from the Galveston court’s district to the San Antonio court’s district.[35]

- In 1941, Coleman and Brown Counties were moved from the Austin court’s district to the Eastland court’s district.[36]

In 1957, following Hurricane Audrey, which severely damaged the Galveston County courthouse, the Legislature authorized the Galveston court (the First Court of Appeals) to sit in either Galveston or Houston.[37] It has been located in Houston ever since (along with the Fourteenth Court of Appeals, which the Legislature established in 1967, as discussed below).

In 1963, the Legislature created the twelfth and thirteenth intermediate appellate courts, locating them in Tyler and Corpus Christi.[38] The Legislature explained that the creation of the new courts was necessary because of “[t]he excessive number of cases on the dockets of the First, Fourth and Fifth Supreme Judicial Districts of Texas and the tremendous increase in litigation in these three (3) Districts [was] causing an impossible workload on the judges thereof.”[39] In a separate bill, the Legislature put Colorado County—which it had included in the new Corpus Christi court’s district only a few weeks before—into the Houston court’s district.[40] Thus, the Corpus Christi court ended up with a twenty-county district running along the Gulf Coast, from southwest of Houston to the Rio Grande Valley. The new Tyler court’s district comprised eighteen counties, ten of which were removed from nearby districts, but eight of which remained in their previous districts. When added to the Hunt County overlap created in 1934, Texas then had a total of nine counties in northeast Texas in overlapping appellate court districts.[41] As to the newest eight counties in overlapping districts, the Legislature did not devise a mechanism for allocating cases between the competing courts as it had done with Hunt County in 1934.

Placing a court in Tyler—which is reasonably close geographically to Dallas (100 miles), Texarkana (130 miles), and Waco (130 miles)—is difficult to understand, except for the fact that the Legislature could not increase the number of justices on the nearby courts because of the constitutional restriction of three justices per appellate court. Situating a court in Corpus Christi to serve south Texas was not illogical at the time, given (again) the fact that the number of justices on the San Antonio court could not be increased. Corpus Christi had a population of 167,690 in 1960. The Rio Grande Valley, which is served by the Corpus Christi court, had three cities with significant populations in 1960—Brownsville (48,040), Harlingen (41,207), and McAllen (32,728)—but collectively they were not as large as Corpus Christi. And Laredo, with a population of 60,678 in 1960, which was included in the district, was slightly closer to Corpus Christi than the Rio Grande Valley (the other possible site for the court).

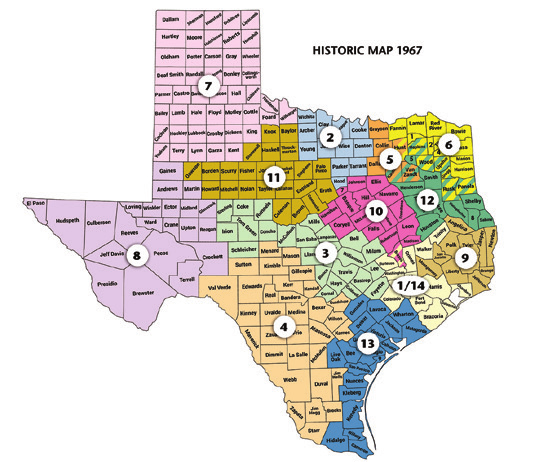

Finally, still faced with the constitutional restriction on the number of justices who could serve on an intermediate appellate court and an increased caseload in the Houston area, the Legislature created the last of Texas’s three-justice intermediate appellate courts in 1967.[42] The fourteenth court was a mirror of the first court, having the same geographic and substantive jurisdiction. The Legislature also added Brazos County, which was in the Waco court’s district, to both Houston courts’ districts, but did not remove it from the Waco court’s district.[43] In this instance, the Legislature did not dictate the court in which an appeal from overlapping counties was to be filed, as it had with Hunt County in 1934. The Legislature, however, required the clerks of the two Houston courts to “from time to time equalize by lot or chance the dockets of the two courts.”[44]

And so, by the end of 1967, six of Texas’s fourteen intermediate appellate courts (Dallas, Texarkana, Tyler, Waco, and both Houston courts) had districts that overlapped with some other appellate court’s district.

In 1975, a law was enacted allowing the Corpus Christi court to “transact its business at the county seat of any of the counties within its district, as the Court shall determine it necessary and convenient . . . .”[45] The provision was added because “the Thirteenth Supreme Judicial District encompasses a broad geographic area necessitating extensive travel on the part of litigants and attorneys.”[46] A branch of the court was subsequently created in Edinburg, and the court continues to operate today as a single court sitting in two locations.

A significant improvement to the intermediate appellate court system finally occurred in 1977, when the Legislature adopted a resolution to ask Texas voters to amend the Constitution to allow more than three justices to sit on each intermediate appellate court, and to allow the justices to hear and decide cases in three-justice “panels,” rather than having the entire court’s membership participate in all cases.[47] This change to the Constitution, which was approved by the voters in November 1978, would allow the Legislature to address the increased workload of the intermediate appellate courts without further increasing the number of courts. In the same legislative session, the Legislature passed a bill adding three justices to both Houston courts, the Dallas court, and the Fort Worth court. The expansion of these courts was contingent on the voters approving the constitutional amendment. The Houston and Dallas courts were to be expanded immediately upon approval of the amendment by the voters, and the Fort Worth court was to be expanded on January 1, 1983.[48]

By 1979, the Court of Criminal Appeals was overwhelmed with cases.[49] Consequently, the Legislature passed a resolution to ask the voters of Texas to vest the intermediate appellate courts with criminal jurisdiction (to accompany the civil jurisdiction they had possessed for eighty-eight years) and to change the name of the courts from “Courts of Civil Appeals” to “Courts of Appeals.”[50] The voters approved the constitutional amendment in November 1980. The Legislature implemented the constitutional amendment in 1981,[51] giving the intermediate appellate courts jurisdiction over criminal matters, except death penalty cases.[52] The Legislature also added twenty-five appellate justices to the courts, effective September 1981, and added three additional justices to the Austin court, effective September 1982.[53] These additions brought the total number of intermediate appellate court justices in Texas to seventy-nine. During its next legislative session, the Legislature added another justice to the Fort Worth court,[54] bringing the total number of justices on these courts to eighty, where it remains today. Texas’s estimated population in 1984 was 16,007,088,[55] meaning Texas had one intermediate appellate court justice for every 200,088 residents of the state.

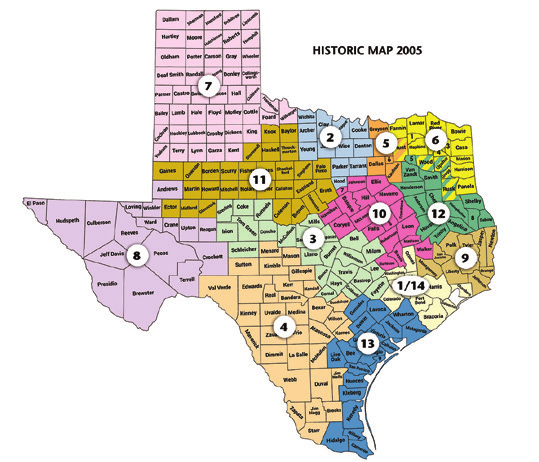

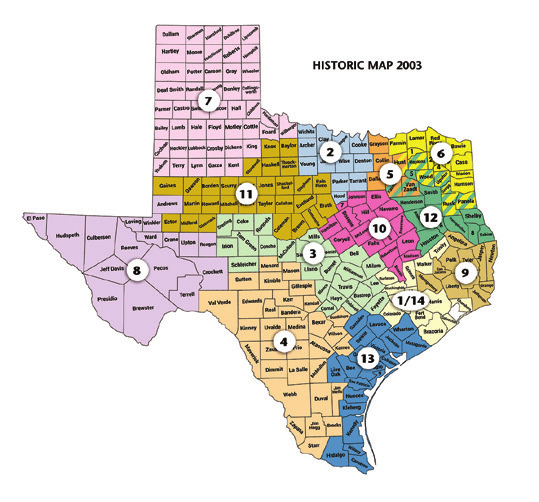

In the early 2000s, the Legislature began some modest reapportionment of the intermediate appellate courts, partly to address the overlapping districts.[56] In 2003, the Legislature moved Ector, Gaines, Glasscock, Martin, and Midland Counties out of the El Paso district and into the Eastland district, which was chronically underutilized.[57] The El Paso court then was reduced from four justices to three, and the Beaumont court was increased from three justices to four.[58] The Legislature also removed Brazos County from the two Houston districts, leaving it only in the Waco district, eliminating one instance of overlapping districts.[59]

In 2005, the Legislature removed Burleson, Trinity, and Walker Counties from the two Houston districts.[60] Burleson and Walker Counties were added to the Waco district, and Trinity County was added to the Tyler district.[61] Van Zandt County was removed from the Dallas district but remained in the Tyler district.[62] Angelina County was moved from the Beaumont district to the Tyler district.[63] Hopkins, Kaufman, and Panola Counties were removed from the Tyler district, leaving Hopkins and Panola in the Texarkana district and Kaufman in the Dallas district.[64]

The structure of the intermediate appellate court system in Texas has remained unchanged since 2005. A total of eighty justices sit on these courts, a number that has not changed since 1984. Appellate court justices have not been reallocated since 2003, and counties have not been moved between districts since 2005. Texas’s estimated population in 2019 was 28,995,881, yielding an average population per justice of 362,449—an eighty percent increase since 1984.

There are three broad conclusions to be drawn from reviewing the structural history of the intermediate appellate courts:

- First, Texas has such a large number of intermediate courts of appeals because an artificial limit on the number of justices who could serve on an appellate court was included in the 1891 constitutional amendment. One cannot imagine the structure of this court system developing as it did in the absence of this constitutional limitation. Instead, if the number of justices on existing courts could have been increased before 1977, Texas would have fewer than fourteen intermediate appellate courts today.

- Second, the boundaries of the intermediate appellate courts have consistently changed over time. The courts’ boundaries have been altered seventeen times since the first three courts were created in 1892. Even after reaching the final number of fourteen courts, the Legislature has continued to change the courts’ boundaries.

- Third, there is no impediment to an appellate court officially sitting in more than one county, while its justices are elected by voters of the whole district. For decades, the Corpus Christi court has had branches in both Corpus Christi and Edinburg.

B. Districts’ Populations and Caseloads

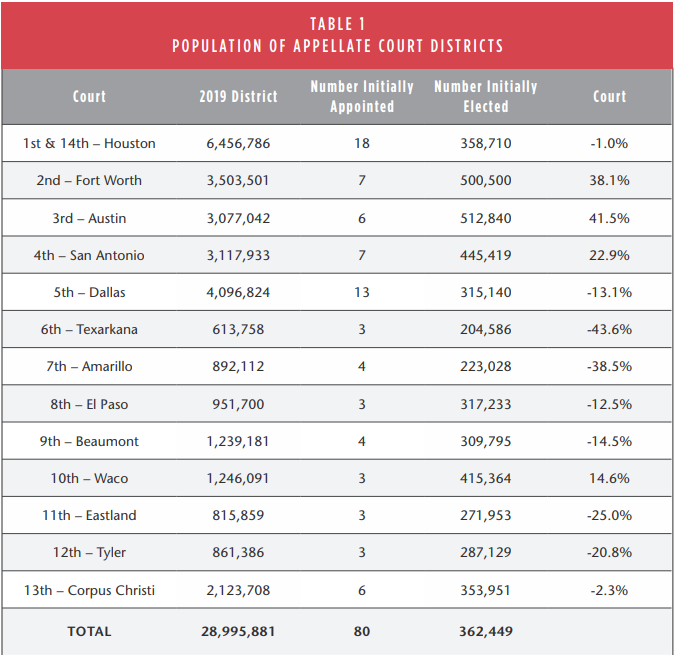

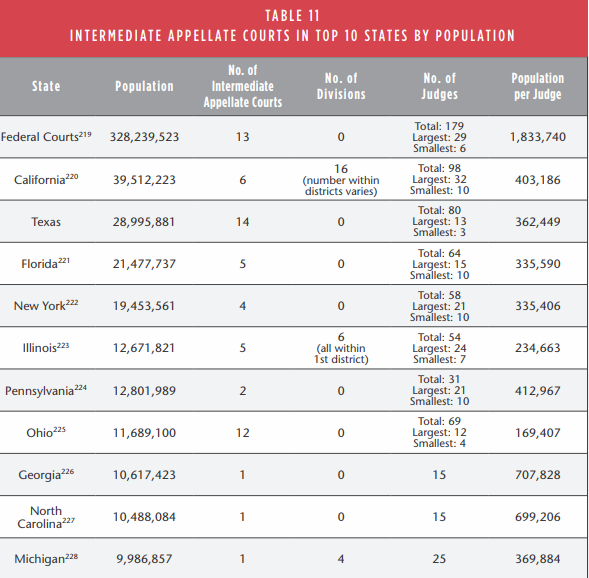

Because the Texas Constitution initially permitted only three justices to serve on each of Texas’s intermediate appellate courts, the Legislature addressed the problem of increasing caseloads by creating additional courts over approximately seventy years.[65] From 1892 to 1967, the number of intermediate appellate courts increased from three to fourteen, with many of the newer courts being established in smaller metropolitan areas with lower populations and fewer cases.[66] Today, Texas’s largest intermediate appellate court (by number of justices) is located in Dallas. It has thirteen justices serving a six-county area, with one of those counties being shared with another appellate court. The two Houston courts, taken together, have eighteen justices serving a ten-county area. The five smallest courts—Texarkana, El Paso, Waco, Eastland, and Tyler—have three justices each, but larger geographic districts.[67] The Tyler court serves seventeen counties, four of which are shared with Texarkana. The Waco court serves eighteen counties. The Texarkana court hears appeals from nineteen counties, five of which are shared with either the Tyler or Dallas court. And the Eastland district covers twenty-eight counties. In terms of the number of counties served, the four-justice Amarillo court is the largest, having a district containing forty-six counties. As shown on Table 1, the population served by each court varies greatly, even on a per-justice basis.

As Table 1 shows, the Texarkana, Amarillo, Eastland, and Tyler districts are significantly underpopulated on a per-justice basis, and the Beaumont, Dallas, and El Paso districts are somewhat underpopulated. The Austin, Fort Worth, and San Antonio districts, on the other hand, are significantly overpopulated.

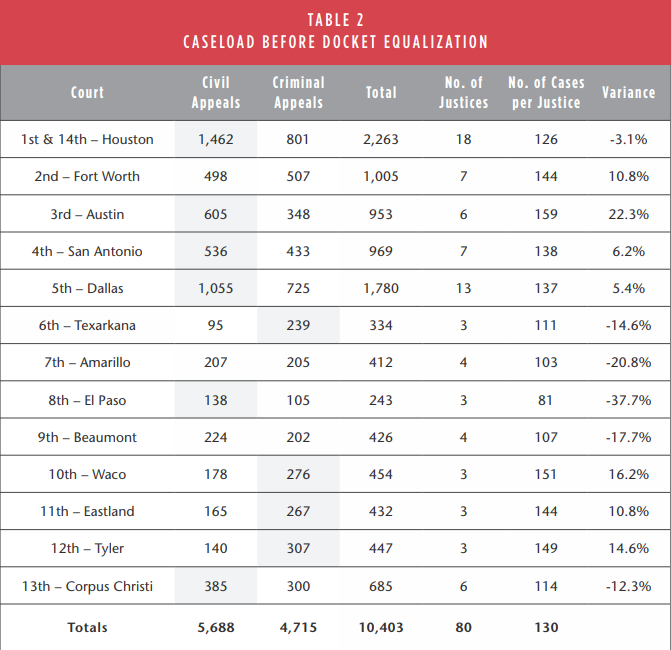

During the fiscal year that ended August 31, 2019,[68] 5,681 civil cases and 4,714 criminal cases were filed in Texas’s intermediate appellate courts, for a total of 10,395 filings.[69] The number of filings in 2019 is not significantly different from the ten-year average of 5,465 civil filings and 5,516 criminal filings, for a total of 10,981 new case filings per year, on average.[70] These courts’ workloads are not evenly distributed when viewed on a per-justice basis, as reflected in Table 2—at least not before docket equalization transfers are completed.

The highlighting in Table 2 shows instances when there is more than a ten percent differential between civil and criminal filings in a court (i.e., more than fifty-five percent of the appeals are of one type or the other). Five of the six “large” courts (those having six or more justices)—Austin, Corpus Christi, Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio—received more civil than criminal appeals, in many instances by large margins. Among the large courts, only Fort Worth received more criminal than civil appeals in 2019, although the difference was modest. Among the smallest courts (those having only three justices), four out of five received more criminal than civil appeals. Of the three-justice courts, only El Paso received more civil than criminal appeals.

Table 2 also shows the wide disparity in the natural caseload of the courts of appeals, at least for FY 2019. The El Paso, Amarillo, Beaumont, Texarkana, and Corpus Christi courts received too few appeals on a per-justice basis compared to their sister courts. But, as shown in Table 1, all of these courts—except Corpus Christi—sit in significantly underpopulated districts, which would naturally result in the courts receiving fewer appeals. Corpus Christi fits the pattern, but not as clearly. It sits in a district that is marginally underpopulated, yet it received meaningfully fewer appeals.

The Austin, Waco, and Tyler courts, on the other hand, received too many appeals, as did the Fort Worth and Eastland courts, to a lesser extent. Austin, Fort Worth, and Waco sit in districts that are significantly overpopulated, which accounts for these courts receiving relatively more appeals than other courts. Oddly, Eastland and Tyler sit in districts that are significantly underpopulated, yet they received relatively more appeals than other courts. Eastland’s district includes Ector and Midland Counties, in the heart of the Permian Basin, and so oil and gas-related prosecutions and litigation may have accounted for Eastland’s disproportionate caseload. The Tyler court shares four counties with the Texarkana court, and so it is possible some litigants chose to file their appeals in Tyler rather than Texarkana, thus inflating Tyler’s numbers. But the four shared counties have relatively small populations and relatively few appeals, and so even if this hypothesis is true, it cannot account for all of the increased caseload Tyler experienced in 2019.

Despite the anomalies presented in Eastland and Tyler, when Tables 1 and 2 are read together, they show that population is a sound, but not perfect, predictor of caseloads. When all of the districts having excessive population (on a per-justice basis) are aggregated, overpopulated districts have thirty-one percent more residents and receive thirteen percent more cases, while underpopulated districts have eighteen percent fewer residents and see six percent fewer cases.[71] The two Houston courts tend to prove the general point that caseloads follow population counts. The Houston district is barely underpopulated and the Houston courts’ combined caseloads are only slightly below the average.

C. Docket Equalization

Any multi-court system will have variances in caseloads. Because the 1891 amendment to the Texas Constitution limited each intermediate appellate court to three justices, the only options for docket equalization were to create more courts, temporarily assign justices to the over-worked courts, redistribute counties between existing courts, or allow the transfer of cases between the courts to equalize their dockets.

Between 1892 and 1967, the Legislature repeatedly created new appellate courts to address burgeoning caseload, and it repeatedly reconfigured the appellate courts’ districts. In addition, in 1895—only two years after creating the first five intermediate appellate courts—the Legislature passed a law compelling the Texas Supreme Court to “equalize as nearly as practicable the amount of business upon the dockets of the different courts of appeals by directing the transfer of cases from such of said courts as may have the great number of cases upon their dockets to those having a less amount of business upon their dockets.”[72]

The statutory provision requiring the Supreme Court to transfer cases to equalize the intermediate appellate court dockets remained law until 1984.[73] In 1985, when court-related provisions of the Texas Revised Civil Statutes were recodified into the new Texas Government Code, the old provision for transferring cases between courts of appeals to equalize dockets was generalized to provide: “The supreme court may order cases transferred from one court of appeals to another at any time that, in the opinion of the supreme court, there is good cause for the transfer.”[74]

In 1999, however, the Legislature returned to explicitly requiring the Supreme Court to transfer cases among the courts of appeals for docket equalization, stating in the general appropriations act, “It is the intent of the Legislature that the Supreme Court equalize the dockets of the fourteen courts of appeals. Equalization shall be considered achieved if the new cases filed each year per justice are equalized by ten percent or less among all the courts of appeals.”[75] The shortcoming of this legislative mandate is that it treats all appeals—civil, criminal, family, administrative, and others—equally. Nonetheless, the ten percent equalization mandate remained in each general appropriations act through the 85th Legislature in 2017,[76] effectively preventing the Supreme Court from equalizing workloads based on any factors other than the number of justices and the number of cases. The mandate, however, was not included in the general appropriations act passed by the 86th Legislature in 2019.[77] Presumably, then, the Supreme Court once again has discretion in transferring cases between the intermediate appellate courts.

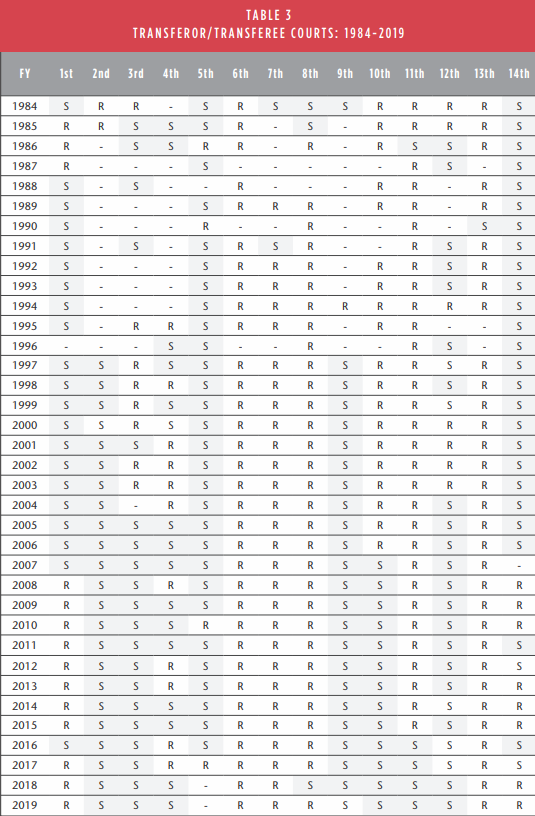

For decades, the Texas Supreme Court has transferred cases among the courts of appeals to equalize these courts’ dockets[78] without choosing specific cases, or types of cases, to transfer. Instead, it orders the transfer of the first number of cases filed in a court of appeals on or after a specified date, but excludes original proceedings, appeals in cases involving termination of parental rights, and “those cases that, in the opinion of the Chief Justice of the transferring court, contain extraordinary circumstances or circumstances indicating that emergency action may be required.”[79]

As shown on Table 3, over the thirty-five-year period since the creation of the eightieth intermediate appellate court judgeship in 1983, the courts in Texarkana, Amarillo, El Paso, Eastland, and Corpus Christi have tended to have lighter caseloads relative to other courts, and are therefore the recipients of transferred cases. For a great majority of years, the Dallas court was overburdened and sending cases to other courts. Beyond that, it is difficult to discern any trends that have lasted through the entire period from 1984 to 2019.

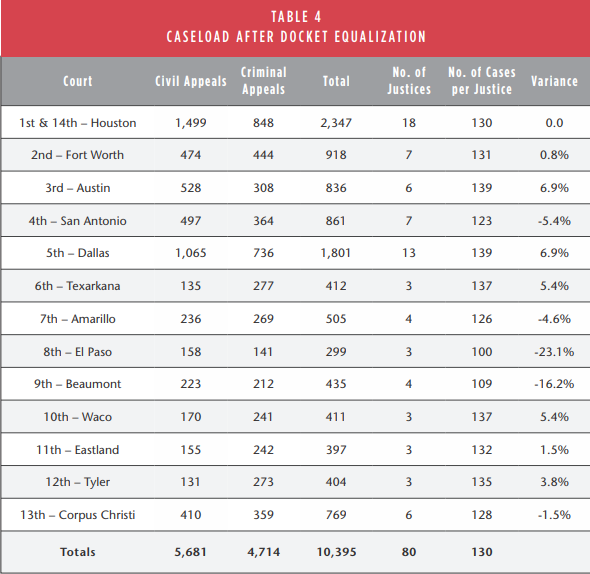

In FY 2019, the Supreme Court transferred 442 cases—about 4.3 percent of the appeals filed in that fiscal year—between the courts of appeals to help equalize dockets.[80] The Fort Worth, Austin, San Antonio, Waco, Eastland, and Tyler courts were transferor courts. The remaining courts were transferee courts. After these transfers, the caseload variance was under ten percent for all courts, except El Paso and Beaumont, as shown in Table 4.

After the equalization transfers were made, all of the courts having six or more justices handled more civil appeals than criminal appeals, while all of the courts having four or fewer justices, except the Beaumont and El Paso courts, handled more criminal appeals than civil appeals. The dockets of the Beaumont and El Paso courts were almost evenly divided between civil and criminal cases.

Today, the Texas Government Code provides a number of rules governing transferred cases, several of which are designed to ease the burden on the parties and their attorneys. The justices of the court of appeals to which a case is transferred must hear oral argument at the place from which the case was transferred, with two exceptions:[81] First, the parties may collectively request the case be heard by the transferee court in its own courtroom.[82] Second, if the transferor court regularly sits in a place that is thirty-five or fewer miles from a place where the transferor court regularly sits, then the transferee court can choose to hear the case in the place where it regularly sits.[83] In addition, at the discretion of the chief justice of the transferee court, the court may hear oral argument in a transferred case through the use of teleconferencing technology.[84]

Docket equalization, and the resulting transfer of cases, is generally unpopular with litigants, lawyers, and justices. In one instance, for example, three appeals in the same case were heard by three different courts of appeals. In Harris County v. Walsweer, the plaintiff was shot by law enforcement officers while outside his estranged wife’s house.[85] Later, he sued the officers and their employer, Harris County, for the injuries he suffered in the confrontation.[86] Trial resulted in an instructed verdict against Harris County and a multimillion-dollar judgment against the officers.[87] An appeal was taken and the case transferred to the Eastland Court of Appeals to equalize dockets.[88] The Eastland court affirmed the judgment against the officers and reversed the judgment in favor of Harris County.[89] On remand, the Harris County trial court entered a summary judgment, holding that Harris County was liable to pay the judgment rendered against the officers because they acted in their official capacities.[90] Harris County appealed, and this appeal was transferred to the Texarkana Court of Appeals to equalize dockets.[91] The Texarkana court reversed the judgment because the summary judgment record was deficient, and remanded the case to the trial court for further proceedings.[92] On remand from the second appeal, the trial court entered another summary judgment against Harris County for the plaintiff’s damages.[93] A third appeal was taken.[94] This time, the case was not transferred, but, instead, it was decided by Houston’s First Court of Appeals. The Houston court affirmed the judgment against Harris County.[95] Thus, one case yielded three appeals to three different courts.

In addition to the prospect of having serial appeals decided by different courts, the transferring of cases, according to a State Bar of Texas task force, causes “significant inefficiencies for parties, courts and clerks [and] diminish[es] the electorate’s ability to hold elected judicial officials accountable, requires citizens to bear the cost of deciding excess appeals from outside the region, and undermines a justice’s ethical obligation to handle cases filed in that court.”[96]

This Foundation stated in a 2007 report:

Docket-equalization transfers are disliked . . . . Some commentators argue that different local rules or the unfamiliarity of arguing in a transferee court may affect litigants, and some attorneys believe that a transferee court is more apt to reverse a transferred case than a case arising in its own district. The uncertainty caused by the transfer of cases may well affect judges as well. One appellate judge noted that it is “fundamentally unfair for the trial judge[’s] conduct to be determined by standards subject to the whims of the transfer system.” [97]

Additionally, in at least one instance, docket equalization did not work as intended. In April 2018, the Texas Supreme Court issued five administrative orders on a single day, transferring back a total of eighty-two cases previously sent to the El Paso court and returning those cases to the five different transferor courts from which they originated.[98] Many of those cases had been pending for more than three years.[99] This means that the parties and attorneys involved in the cases filed appeals, then had the cases transferred to the El Paso court from their local appellate court districts where the lower court proceedings had occurred, and watched as the cases languished in the El Paso court for several years, only to have the cases then transferred back to the originating appellate court for disposition. The years of delay doubtless added untold costs and anguish to the litigants. The cases involved matters such as property disputes, divorce disputes, administrative law matters, taxation cases, and business cases, among others, which can be negatively impacted by the passage of time.

One of the major criticisms of docket equalization transfers[100] was remedied by the Texas Supreme Court in 2008, when the Court promulgated a rule to deal with the use of precedent in transferred cases. The problem was that transferred cases were tried under precedent established by the court of appeals for the district in which the trial court was located, but reviewed by a different court of appeals applying its own precedent, which might be inconsistent or conflicting. The Supreme Court promulgated an appellate procedure rule providing that in cases transferred from one court of appeals to another, the transferee court must decide the case in accordance with the precedent of the transferor court.[101] “The rule requires the transferee court to ‘stand in the shoes’ of the transferor court so that an appellate transfer will not produce a different outcome, based on application of substantive law, than would have resulted had the case not been transferred.”[102] The transferee court’s opinion may state whether the outcome would have been different had the transferee court not been required to decide the case in accordance with the transferor court’s precedent.[103] The transferee court is not, however, required to follow the transferor court’s local rules or otherwise supplant its own local procedures with those of the transferor court.[104]

D. Operations and Productivity

- Working in Panels

Texas’s intermediate appellate courts had three justices each until a constitutional amendment passed in 1978 allowing the Legislature to add justices to the courts. Thus, until the number of justices began to increase in the late 1970s, the justices on the courts sat en banc to decide cases, meaning each case was heard by all the justices on the court. Upon passage of the constitutional amendment in 1978, an additional three justices were added to both Houston courts and the Dallas court, and the statute was amended to provide that these courts had to “sit in panels of not less than three Justices.”[105] As justices were added to the courts (largely in 1981), the requirement that courts having more than three justices sit in panels of “not less than three” remained in effect.[106] Today, Texas’s intermediate appellate courts are required to sit in three-justice panels.[107] The method used to assign justices to panels with more than three justices is not dictated by statute or rule and is not uniform.[108] But the panels must rotate, at least to some extent.[109] All of the courts rotate panel assignments in some way to avoid “doctrinal disharmony” on the court, as described by one appellate court justice:

With a fixed panel, the risk of the court’s doctrinal disharmony rises. For example, a court of nine justices working as three-justice, non-rotating panels could tend to become, in effect, three separate tribunals and lose doctrinal coherence. It would defeat the purpose of adding justices to a court to have decisions of a fixed tribunal be reviewed by the entire court sitting en banc. Appellate justices are fully occupied with hearings on their three-justice panels, and sitting en banc interferes with their normal work and draws time and energy away from their regular duties. As a result, appellate justices on larger courts disfavor having many en banc hearings.

This concern of maintaining doctrinal coherence is reduced when the court sits in rotating three-justice panels. The justices are few enough so that each can frequently sit with the others, and they are apt to develop a measure of collegiality. This allows justices to be aware of all panel opinions and be familiar with the entire range of the court’s jurisprudence. All of the courts of appeals in Texas that have expanded beyond three justices have adopted the panel rotation model. However, each has developed its own internal procedures for how these panels are constituted and their time duration.[110]

- Overall Productivity

Texas’s intermediate appellate courts reached their full complement of eighty justices on September 1, 1983. Texas’s estimated population the following year was 16,007,088,[111] meaning Texas had one intermediate appellate court justice for every 200,088 residents of the state. These 16 million Texans generated 7,386 appeals in the fiscal year that ended August 31, 1984—3,120 civil cases and 4,266 criminal cases—or about 4.6 appeals per 100,000 residents.[112] The courts disposed of 8,274 cases (a 112 percent clearance rate) during that fiscal year, ending the year with 5,717 pending cases, down from 6,605 at the end of the prior fiscal year.[113] The justices wrote 7,841 opinions—an average of ninety-eight opinions per justice.[114] Sixty-four percent of the opinions were original opinions on the merits and twenty-seven percent were per curiam opinions.[115] The average time between submission (the date the case is argued or the date the case is officially under review by the court when argument is not held) and disposition was 2.3 months for civil cases and 1.5 months for criminal cases.

Thirty-five years later—during the fiscal year ending August 31, 2019—the intermediate appellate courts received 10,395 cases—5,681 civil and 4,714 criminal cases. They disposed of 10,294 cases during the year (a ninety-nine percent clearance rate) and issued 9,897 opinions, an average of 124 per justice. Sixty-three percent of the opinions were original opinions on the merits, and twenty-five percent were per curiam opinions.[116] There were 6,509 cases pending at the end of the fiscal year. On average, the time between submission and disposition was 1.5 months for civil cases and 1.4 months for criminal cases in FY 2019.[117]

Texas’s estimated population in 2019 was 28,995,881, yielding an average population per appellate court justice of 362,449—an eighty percent increase since 1984. Even though Texas’s population increased by eighty percent over the thirty-five-year period, the number of appeals filed in the courts increased only forty-one percent over the same time period. In FY 1984, about forty-two percent of the appeals were civil cases and fifty-eight percent were criminal cases. In FY 2019, civil case filings significantly outpaced criminal case filings by about a fifty-five percent to forty-five percent margin.[118] The reason for the transformation from mostly criminal to mostly civil cases is not apparent from the historical documents. The number of dispositions and opinions increased over the thirty-five-year period, but only twenty-five and twenty-six percent, respectively. The number of cases that remained pending at the end of the fiscal year increased about fourteen percent, from 5,717 to 6,509. The number of appeals per 10,000 population decreased to 3.6 in FY 2019 from 4.6 in FY 1984.

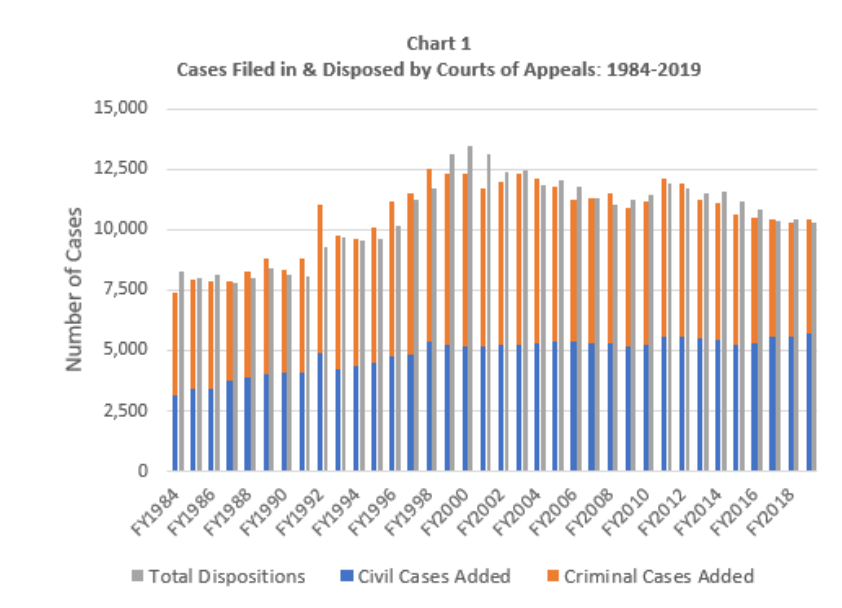

Chart 1 shows the number of cases filed in, and disposed of by, the courts of appeals for each fiscal year since 1984.

The data shows that, while Texas’s appellate courts are busier in 2019 than they were thirty-five years earlier, the increased population is not generating the number of appeals that might have been expected. In other words, the courts are not as busy as an eighty percent increase in population would suggest they should be.

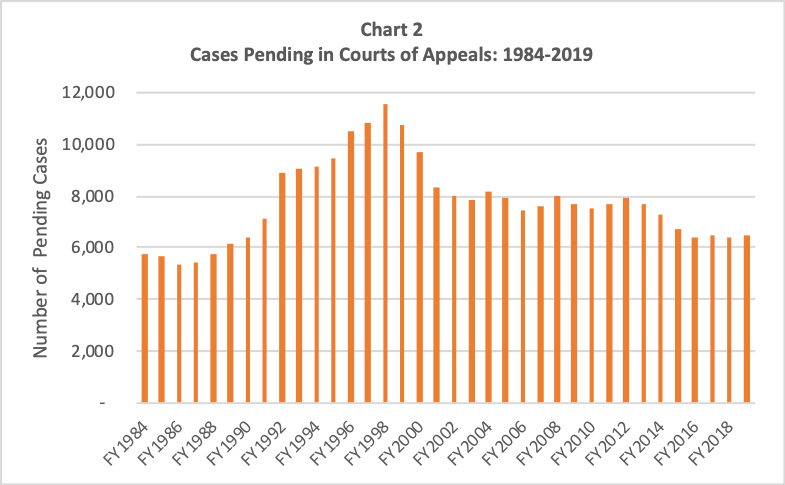

A large number of cases were transferred from the Court of Criminal Appeals to the intermediate appellate courts when they were given criminal jurisdiction in 1981,[119] thus increasing these courts’ backlogs. As Chart 2 shows, Texas’s intermediate appellate courts began falling farther behind each year, beginning in FY 1987. By FY 1998, the backlog exceeded 11,500 cases—a number exceeding a full year of new case filings. The courts began to chip away at the backlog in FY 1999, largely through the use of visiting justices.[120] In most years since FY 1999, the courts’ collective clearance rate—the number of disposed cases as a percentage of the number of new cases—has exceeded 100 percent, as shown in Chart 1. As a result, the courts have reduced the backlog by forty-four percent since FY 1998. Chart 2 shows the number of cases still pending in the courts at the end of each fiscal year.[121]

The reduction of the backlog means the courts are able to dispose of cases fairly expeditiously. Over the most recent ten years, the average time from submission to disposition of criminal cases is 1.6 months, while the average time for civil cases is 1.8 months. It takes 7.8 months, on average, from the date a civil appeal is filed to the date it is resolved. The average for criminal cases is 8.9 months from filing to disposition. Thus, whether it is a civil or criminal case, Texans can expect a resolution of their appeals, on average, within nine months after the appellate process is commenced.

Unquestionably, the eighty justices serving on Texas’s appellate courts are more productive today than they were thirty-five years ago. They are handling more appeals and writing more opinions every year than they did in 1984. These courts’ increase in productivity appears to be attributable to three major factors—technology, staffing, and visiting justices—which are discussed in the following sections.

- Increases in Productivity Due to Technology

On December 11, 2012, the Texas Supreme Court handed down an order requiring the electronic filing of all documents in civil cases in the Supreme Court, courts of appeals, district courts, statutory county courts, constitutional county courts, and statutory probate courts.[122] The Court’s introduction to its order explained:

Disputes in court require the exchange of information. The primary medium of that exchange has been paper. Texas courts have struggled for over a century to process, manage, and store court documents. With the information age, it is now possible to receive and store those documents digitally. Texas courts first experimented with this new medium in the 1990s when two district courts urged lawyers to file documents electronically. The benefits were immediate. With electronic filing, storage expenses decreased dramatically. Clerks that formerly spent time sorting and file-stamping documents could be assigned to more productive activities. Documents were no longer damaged or lost. The public, lawyers, and judges could instantly access vital pleadings, accelerating the progress of litigation. These efficiencies prompted the judiciary to initiate a pilot project in January 2003 to test and refine the e-filing model. That model was instituted statewide in 2004 . . . .[123]

The Court ordered that “E-filing will be mandatory in civil cases . . . [and] attorneys must e-file all documents in civil cases, except documents exempted by rules adopted by this Court . . . .”[124] Electronic filing in civil cases in the courts of appeals was to begin on January 1, 2014.[125] Electronic filing in civil cases was phased in for trial courts, with courts in small-population counties having until July 1, 2016, to implement electronic filing.[126]

On June 30, 2016, the Court of Criminal Appeals followed the Supreme Court’s lead.[127] “Having observed the transition to electronic filing in the Court and in civil cases in other appellate courts and district and county courts . . . , this Court has concluded that mandatory electronic filing in criminal cases will promote the efficient and uniform administration of justice in Texas courts.”[128] The appellate courts were to begin immediately. Electronic filing in the trial courts was phased in, with the smallest counties having until January 1, 2020.[129]

At this point, electronic filing is mandatory for all attorneys filing civil, family, probate, or criminal cases in the Supreme Court, Court of Criminal Appeals, courts of appeals, district courts, and county courts in Texas. Non-attorneys are encouraged to file electronically as well, although not required to do so. Thus, all trial courts that send appeals to Texas’s intermediate appellate courts receive pleadings, motions, and other documents through an internet-based electronic-filing system. The courts of appeals have been receiving appellate briefs in electronic form, almost exclusively, for several years.

Broadly speaking, the appellate process follows these steps:

- A party who is unhappy with a trial court’s judgment files a notice of appeal to begin an appeal.[130] This person (the appellant) also requests that the appellate record be prepared and filed with the court of appeals.[131]

- The appellate record consists of two parts: the clerk’s record and the reporter’s record.[132] The clerk’s record includes the items (mostly documents) filed with the trial court clerk while the case is proceeding.[133] The reporter’s record is the transcript of pre-trial hearings and trial. It includes the exhibits offered into evidence at trial.[134]

- After the two parts of the record are sent to the court of appeals, the parties must file their briefs.[135] The appellant files a brief to which the other party (the appellee) responds.[136] The appellant may file a second brief, replying to the appellee’s response.[137] In their briefs, the parties may request the opportunity to present oral arguments to the court of appeals.[138]

- After the briefing is completed, the court of appeals may order oral argument (whether requested or not), or the court may inform the parties that it will decide the appeal on the papers.[139] For cases in which oral argument is allowed, the case is considered submitted at the conclusion of the argument. For cases in which oral argument is not allowed, the case is considered submitted after briefing is complete.[140]

- After submission, the court of appeals writes an opinion, and the appellate court clerk issues a judgment in accordance with the opinion.[141] The judgment will either affirm or reverse the trial court’s judgment.[142] The time between submission and decision averages less than two months for Texas’s intermediate courts of appeals.[143] That is to say, the justices review the appellate record, study the parties’ briefs, conduct legal research, and write an opinion, all in less than sixty days, on average.

Before electronic filing rules were implemented, the trial court clerk prepared the clerk’s record by gathering the documents, hand-numbering the pages from beginning to end, preparing an index and a cover, and binding everything together with an official certificate. Then the clerk’s record was sent to the court of appeals. In complex cases, the clerk’s record might consist of several thousand pages gathered into multiple volumes.

To create the reporter’s record, the court reporter transcribed the notes taken at hearings and trial, printed the transcript on paper, and prepared an index and cover. The court reporter also gathered, organized, and indexed the exhibits offered into evidence at trial. Everything was bound together with an official certificate and sent to the court of appeals. In cases in which trial took weeks or months, the reporter’s record could consist of thousands of pages bound into multiple volumes.

Each volume of the appellate record was bound and sealed so that it would be obvious if someone tampered with it, which made it difficult to copy and use. The appellate court clerk was (and remains today) tasked with prodding the trial court clerk and reporter to ensure the record was timely filed.[144]

Lawyers having financial resources often paid for a copy of the clerk’s and reporter’s records, which they received when the record was filed. Lawyers lacking sufficient resources to obtain a copy of the appellate record would withdraw it from the appellate clerk’s office to prepare the necessary brief. Because briefing is a back-and-forth activity, the record would be withdrawn and returned by the appellant, then withdrawn and returned by the appellee, and withdrawn and returned again by the appellant. All of this activity required the appellate court clerk’s direct involvement and supervision. Handling and organizing appellate records took a substantial amount of time for appellate court clerks, and storing paper records required substantial amounts of space.

Until the 1980s, legal research was conducted in a library full of books. Many of the books were indexes of other books, used to locate statutes, opinions, and other authorities within the vast number of books in the library. Most briefs were typewritten until the early 1980s, with the final version being copied, covered, and bound for filing. Even after computers replaced typewriters, briefs were printed, copied, covered, and bound for filing, until electronic filing was implemented. Again, the appellate court clerk was required to organize and manage all of these paper briefs.

Obviously, lawyers were required to travel to the court of appeals to present oral argument, and still must. But before the advent of overnight delivery services largely negated the need for this travel, a lawyer or the lawyer’s staff often traveled to the court of appeals to file briefs and motions, and to pick up and return the appellate record.

Today, the appellate process bears little resemblance to the one just described. Virtually all items included in the clerk’s record will have been filed with the trial court in electronic form via the internet. The trial court clerk does not gather, number, index, or bind paper documents to create a clerk’s record. Instead, the clerk’s record consists of an accumulation of electronic files sent to the court of appeals and the parties’ lawyers via the internet. The same is largely true for the reporter’s record, although it is not uncommon for trial court exhibits to exist in physical form that must be organized and shipped to the appellate court. But, broadly speaking, the process of preparing a reporter’s record is orders of magnitude easier than it was fifty or even twenty-five years ago. Appellate court clerks are no longer burdened with paper records or paper briefs.

The lawyers conduct legal research using computers that access and sift through massive databases containing every imaginable opinion, statute, or other authority. Briefs are written on computers and filed electronically. The briefs are internally hyperlinked, so that the reader—a justice writing an opinion—can “jump” to specific sections of the brief and instantly see statutes, opinions, and other authorities relied upon in the brief. A lawyer must travel to an appellate court only to present oral argument in those cases in which oral argument is requested and granted.

The court’s opinions, too, are written on computer and released to the parties and public by electronic means. Like the outside lawyers, justices and the lawyers working with the justices to draft opinions conduct research through internet-based databases. They can look at the appellate record on their computer screen and search it electronically. They can write opinions—the fundamental aspect of an appellate justice’s job—from any location where internet access is available. For the most part, the justices must appear in the courthouse only for oral arguments and court conferences.

Unquestionably, technology has helped both the justices and clerks working in Texas’s intermediate appellate courts become more efficient, which partly explains how the courts of appeals have been able to handle an increased workload generated by an increased population without the creation of new judgeships.

- Increases in Productivity Due to Staffing Adjustments

Increases in productivity also are attributable to an enhanced professional staff at the intermediate appellate courts. Of course, appellate court justices do not work alone, and have not worked alone for decades. But the number of lawyers and other professionals employed by these courts to help the justices digest appellate records, conduct legal research, and write opinions has increased over time.

In the beginning, the justices on the courts of appeals conducted research, reviewed the record, and wrote opinions on their own.[145] In 1942–1943, each of the courts had a clerk, two deputy clerks/stenographers, and a porter, in addition to three justices.[146] By the mid-1970s, most of the courts had begun using law clerks (recent law school graduates who worked for the court for a fixed period of time) to assist the justices in opinion writing. The two Houston courts and the Amarillo court had three law clerks each; the Dallas, Corpus Christi, El Paso, San Antonio, and Tyler courts had two law clerks each; the Austin, Beaumont, Fort Worth, and Texarkana courts had a single law clerk each; and the justices on the courts in Eastland and Waco continued to work without attorney assistance.[147] The permanent position of “legal counselor”—now called a “staff attorney”—was created in 1978, when the Dallas and Houston courts were expanded to six justices each.[148]

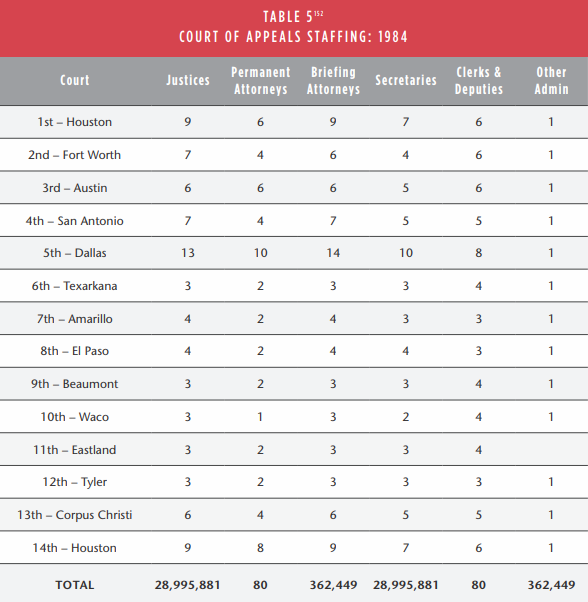

It was not until September 1, 1979, that each justice on all fourteen courts had his or her own law clerk.[149] The intermediate appellate courts were given criminal jurisdiction in 1981, which essentially doubled their workloads.[150] The number of justices on the courts increased from fifty-one to eighty by September 1, 1983. In 1983, the Legislature also dramatically increased the professional staff of the courts of appeals.[151] The Legislature appropriated funds so each justice would have a briefing attorney (formerly called a law clerk), and each court would have at least one permanent staff attorney, although all the large courts had many more than one. The total number of employees, excluding the justices themselves, was 279 in 1984, categorized as shown in Table 5.

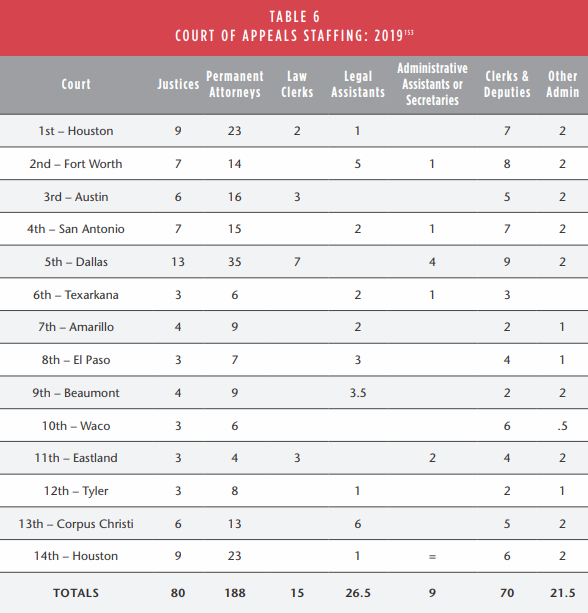

In FY 2019, the courts of appeals employed 330 attorneys, clerks, and others (as shown in Table 6), not including the justices themselves. This is an eighteen percent increase from FY 1984—but a substantially smaller increase than the growth in population (eighty percent) or the rise in caseload (forty-one percent). The number of attorneys (including law clerks), however, has increased from 135 to 203, a fifty percent increase. Sixty-two percent of the courts’ employees were attorneys in FY 2019, compared to forty-eight percent in 1984. There were sixty-four secretaries in 1984, but only nine secretaries/administrative assistants in FY 2019. No court had a person with the title of legal assistant in FY 1984. In 2019, 26.5 legal assistants (non-lawyer having some legal training) were employed by the courts. The number of court clerks (the clerk of the court and all deputy clerks) has increased insignificantly—from sixty-seven to seventy—in the thirty-five years between 1984 and 2019.

The trends are obvious: the courts are relying on staff attorneys and legal assistants (but not temporary briefing attorneys/law clerks) to handle the ever-increasing caseloads, while the need for personnel to actually hammer out opinions on a typewriter or computer keyboard has fallen dramatically, and technological innovations have allowed the clerks’ offices to become substantially more efficient.

- Increases in Productivity Through Use of Visiting Justices

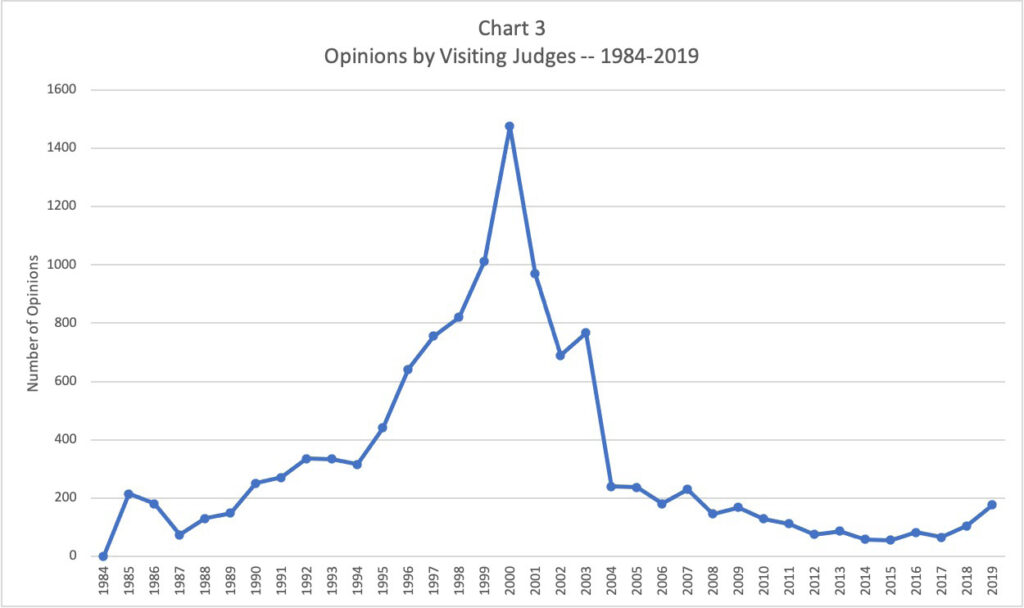

Before the intermediate appellate courts were given criminal jurisdiction in 1981, visiting justices (judges sitting temporarily through an assignment made by the Texas Supreme Court) were seldom used to help the courts manage their caseloads.[154] That began to change in FY 1985, when 215 opinions were authored by “assigned justices.”[155] The number dropped to seventy-four in FY 1987, but then began a sharp rise, reaching a high of 1,474 opinions by assigned justices in FY 2000. Graphically, the spike in the use of visiting justices as depicted in Chart 3 corresponds to the arch in the number of pending cases in Chart 2, thus showing that the use of visiting justices was a key to reducing the courts’ backlog in the early 2000s.

The number of opinions written by visiting justices fell precipitously in FY 2004, to 240, and trended downward from FY 2004 to FY 2017, when sixty-six opinions were authored by visiting justices. The number of opinions by visiting justices increased in FY 2018 and FY 2019 because a regular justice on the Eastland court was not writing opinions due to illness. Presumably, this increase is temporary and the status quo ante will return in FY 2020. The courts will, it is assumed, keep pace with filings without the extensive use of visiting justices going forward.

In sum, the courts of appeals can and do use visiting justices to handle their caseloads. The use of visiting justices has been relatively modest over the past decade, but if caseloads were to increase significantly for a particular court, or for the system as a whole, the assignment of visiting justices remains an avenue for ensuring caseloads do not become unmanageable.

- Productivity of Clerks’ Offices

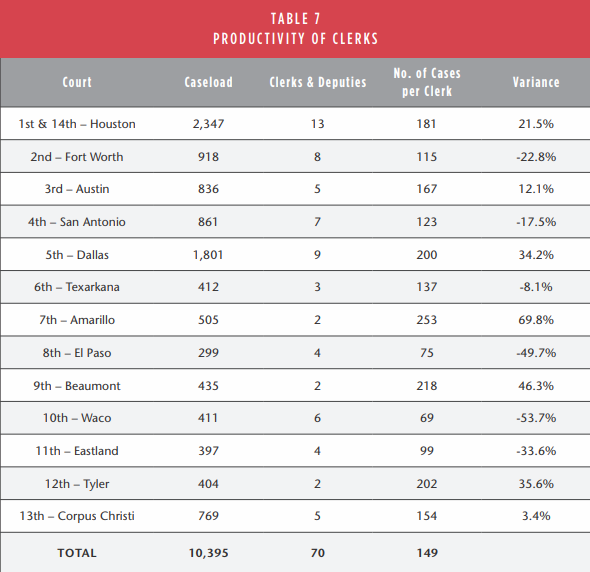

The productivity of the clerks’ offices appears to vary greatly between the courts of appeals. The Constitution provides that each court must appoint a clerk of the court.[156] In addition to the official clerk of the court, all of the clerks’ offices have at least one deputy clerk, and most have more than one deputy, as reflected in Table 7. The Amarillo, Beaumont, and Tyler courts each have a clerk and one deputy clerk. Based solely on the number of new cases handled by the offices, these clerks’ offices are the three busiest in the state. The Dallas court’s clerk’s office also is quite busy. On the other end of the spectrum are the Waco, El Paso, and Eastland clerks’ offices, which—based solely on the number of new cases handled by the offices—appear to be overstaffed.

Each person in the Waco court’s clerk’s office handled only sixty-nine new appellate files in 2019, while each person in the Amarillo court’s clerk’s office handled 253 new appellate files that year—almost four times more. There may, however, be aspects of the clerks’ work being done by other court personnel in busier offices that is not apparent from the public record. Similarly, clerks in what appear to be less productive offices may have responsibilities not shared by clerks on other courts.

E. Court Budgets

Although subject to the appropriations process that is applicable to all governmental entities, Texas’s intermediate appellate courts decide for themselves how they will spend funds allocated to them by the Legislature. The Legislature simply appropriates an amount of money to be provided to each appellate court each biennium and leaves it to each court to make spending decisions.[157] Some courts—like the two Houston courts—use a combination of staff attorneys assigned to a pool and staff attorneys assigned to specific justices to help with opinion writing. On other courts, all staff attorneys are assigned to a specific justice. Some courts—including Austin and San Antonio—have a staff attorney who handles nothing but original proceedings for the court, along with two or three attorneys assigned to each justice. Legal assistants, briefing attorneys/law clerks, and administrative assistants are employed by some courts but not others.

The Legislature, however, dictates performance standards for these courts, typically requiring that the courts resolve at least as many cases as they receive each year (i.e., maintain a 100 percent clearance rate).[158] By dictating performance standards, it is implied that future appropriations can be affected by a court’s failure to meet the standards.

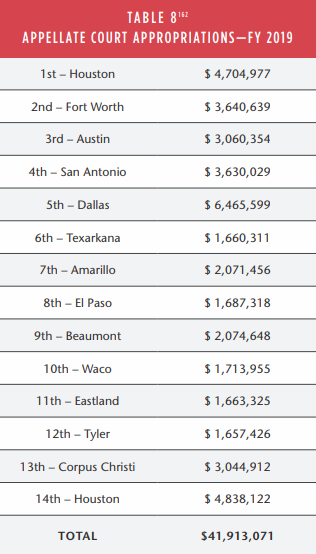

The grand total of all funds budgeted for expenditure by the State of Texas for all purposes during FY 2019 was almost $108 billion.[159] The amount of money appropriated in FY 2019 to operate the entire judicial system in Texas was under $410 million.[160] That is, less than four-tenths of one percent of funds expended by the State of Texas are used to support the judicial system.[161] The amount appropriated to the intermediate appellate courts for FY 2019 was under $42 million, about ten percent of the total budget for the judiciary.

The FY 2019 budget for each of the courts of appeals is shown in Table 8.

About ninety-five percent of the money spent by the courts of appeals is allocated to pay wages and other personnel costs. The amount specifically appropriated to each court, however, does not include funds allocated to the Office of Court Administration that are used to support the intermediate appellate courts, contributions to the judicial retirement system by the Comptroller of Public Accounts for appellate court justices, or amounts paid for health care for appellate court personnel. Legislatively appropriated funds also do not include amounts spent by local governments to provide facilities and other services to support the appellate courts.

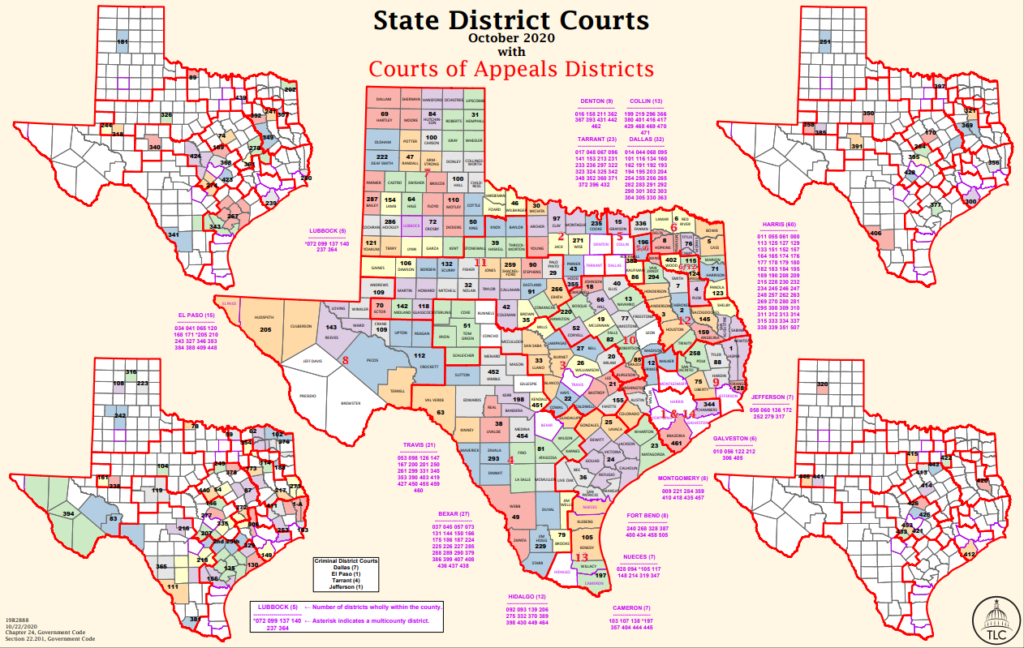

F. Overlapping Appellate Court Districts and Bisecting Trial Court Districts

Texas’s trial courts of general jurisdiction are its district courts. There are 477 district courts in Texas, ninety-seven of which have a multi-county district. Five of Texas’s fourteen intermediate appellate courts (Dallas, Texarkana, Tyler, and both Houston courts) have districts that overlap with other appellate court districts. Fifteen counties sit in the overlapping areas of two appellate court districts,[163] and those fifteen counties contain ninety-six district courts. Texas is the only state in the nation with overlapping appellate court districts.[164]

In the overlapping Houston courts’ districts, the cases are randomly assigned to a court of appeals when the notice of appeal is filed.[165] In the overlapping counties in northeast Texas, on the other hand, a party filing a notice of appeal designates the court of appeals that will hear the appeal.[166] If two parties perfect appeals to different courts, the first to perfect appeal establishes the court that will hear the appeal.[167] This can result in a form of venue shopping—a “race to the courthouse.” For example, in Miles v. Ford Motor Co., both parties to a judgment rendered by a Rusk County trial court filed notices of appeal.[168] The plaintiffs won the race to the courthouse, perfecting an appeal to the Texarkana court, while the defendant subsequently perfected an appeal from the same judgment to the Tyler court.[169] The plaintiffs moved to dismiss the defendant’s appeal to the Tyler court on the ground that the Texarkana court had acquired dominant jurisdiction of the case.[170] The Supreme Court agreed, even in the face of the defendant’s argument that the issues it would raise in the appeal were far weightier than those the plaintiffs would raise.[171] The Texas Supreme Court addressed the existence of overlapping jurisdictions in Miles:

[W]e note that this question arises only because the Legislature has chosen to create overlaps in the State’s appellate districts. We have been unable to find any other state in the union which has created geographically overlapping appellate districts. Most of the reasons which explain such overlaps, such as political expediency, local dissatisfaction with the existing judiciary, or an expanded base of potential judicial candidates, would at most justify the temporary creation of such districts, not permanent alignments.On the other hand, the problems created by overlapping districts are manifest. Both the bench and bar in counties served by multiple courts are subjected to uncertainty from conflicting legal authority. Overlapping districts also create the potential for unfair forum shopping, allow voters of some counties to select a disproportionate number of justices, and create occasional jurisdictional conflicts like this one. The Court thus adheres to its view that overlaps in appellate districts are disfavored.[172]

It is tempting to assume that having two overlapping courts in Houston is inconsequential, but that assumption is incorrect.[173] The two Houston courts are not required and sometimes choose not to follow each other’s precedent. For example, the two Houston courts reached opposite outcomes on the same facts in opinions handed down in 1999 and 2000. In an opinion by the First Court of Appeals, the City of Houston’s assertion of immunity was rejected and three passengers in a car accident allegedly caused by a City employee were allowed to sue the City.[174] A fourth passenger in the same car, however, was barred by the Fourteenth Court of Appeals from suing the City because the court determined the City, in fact, was immune.[175] The outcomes of the two cases—decided by two appellate courts occupying the same courthouse—are plainly inconsistent.

In 2002, the Texas Supreme Court renewed its call for the Legislature to resolve overlapping appellate court districts, saying, “[n]o county should be in more than one appellate district.”[176] The Legislature eliminated some overlapping areas by legislation passed in 2003 and 2005,[177] but overlapping districts remain, as do the problems arising from having overlapping jurisdictions.

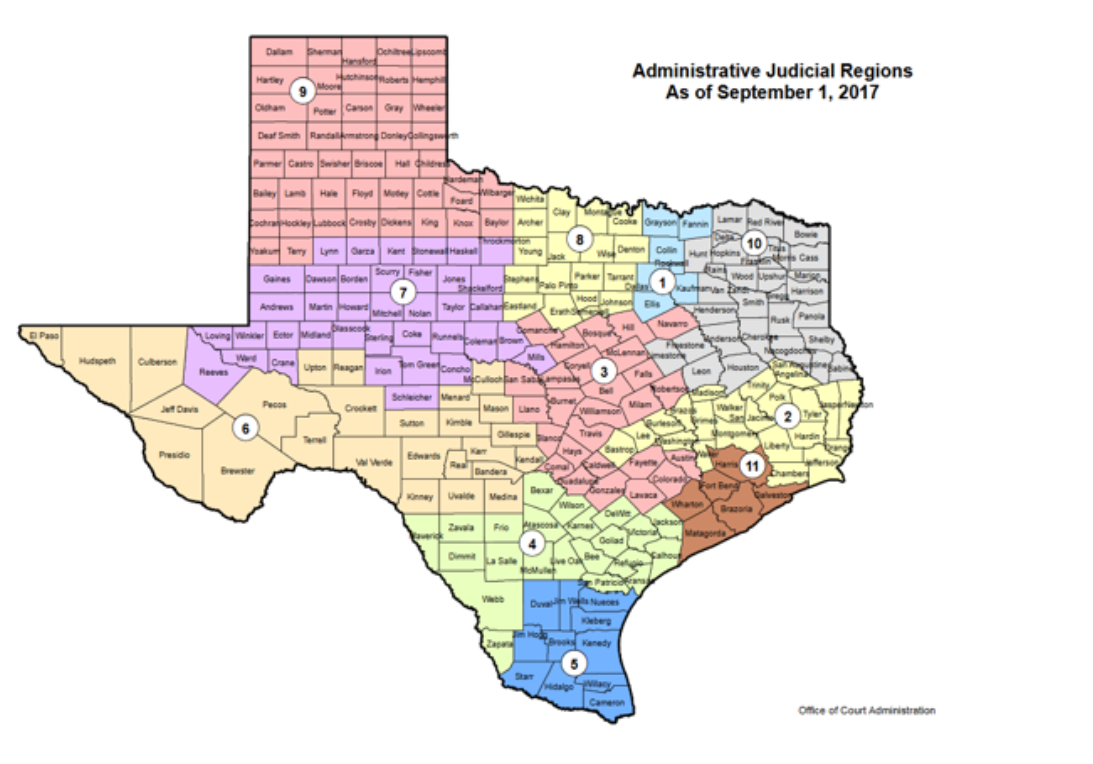

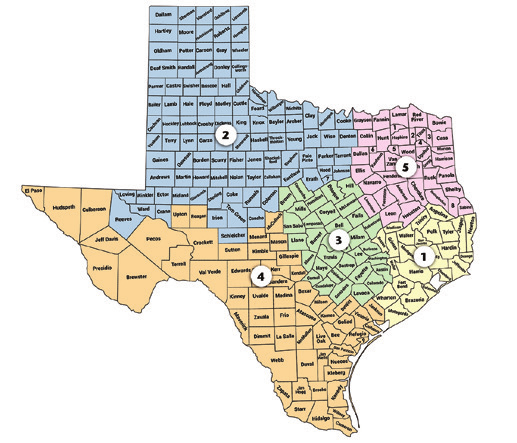

In addition to having overlapping appellate court districts, the appellate courts’ boundaries cut through multi-county trial court districts, as depicted on the following map. Every court of appeals, except the Dallas court, has a boundary that bisects at least one trial court district.

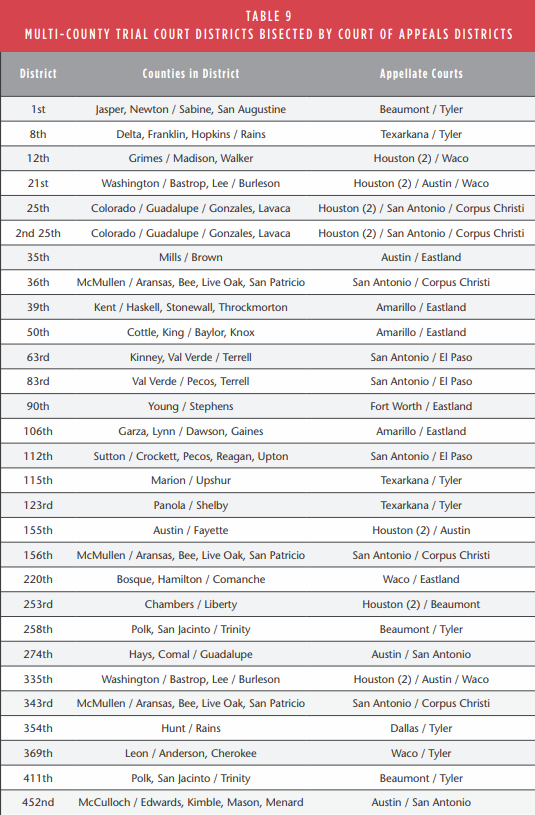

As detailed in Table 9 and shown in the map above, twenty-nine multi-county district courts (thirty percent of the multi-county trial courts in Texas) straddle appellate court district boundaries. Twenty-two judges in these multi-county courts answer to two courts of appeals, three judges answer to three courts of appeals,[178] and four answer to four courts of appeals.[179]

For example, when sitting in Kent County, the judge of the 39th District Court must know and apply the Amarillo court’s precedent; but when he crosses the county line into Stonewall County, he must know and apply the Eastland court’s precedent. Of course, it is possible to know the differences in the precedent of the two courts, and so an argument can be made that this judge—and twenty-eight others like him—are not particularly disadvantaged by having a multi-county district that is bisected by the courts of appeals’ boundary. They can, it may be argued, simply apply the law applicable in the county in which they happen to be sitting on a given day. But saying it is possible for a judge to know, and instantly call to mind, all of the nuanced differences in the precedent of two, three, or four appellate courts in civil, criminal, family, juvenile, and probate law vastly understates the difficulty of the task.

When the ninety-six district courts in overlapping appellate court districts are combined with the twenty-nine district courts whose districts are bisected by an appellate court boundary, a total of 116 of Texas’s 477 district courts—twenty-four percent of the district court judges in Texas—answer to two or more courts of appeals.

G. Uneven Distribution of Judges in Election Cycles

Another less-than-ideal feature of Texas’s intermediate appellate court system is the uneven distribution of justices in the election cycles. These justices are elected by the voters of their districts for six-year terms.[180] When all of the courts were comprised of three justices, one justice on each court was on the ballot each election cycle. In 1977, the Legislature proposed a constitutional amendment to allow the courts to have more than three justices each, which the voters adopted in 1978.[181] The Legislature also passed statutory amendments to implement the constitutional amendment if it passed.[182] Three justices were added to both Houston courts and the Dallas court. At the time, Article V, section 6 of the Texas Constitution provided:

At the first session of . . . the Courts of Civil Appeals which may be hereafter created under this article after the first election of the Judges of said courts . . . [t]he terms of office of the Judges of each court shall be divided into three classes and the Justices thereof shall draw for the different classes. Those who shall draw class No. 1 shall hold their offices two years, those drawing class No. 2 shall hold their offices for four years and those who may draw class No. 3 shall hold their offices for six years, from the date of their election and until their successors are elected and qualified, and thereafter each of the said Judges shall hold his office for six years, as provided in this Constitution.[183]

Similarly, the enabling statute provided that when justices were added to courts, the new justices would “draw lots for their terms of office” after being elected.[184] These provisions ensured that new justices added to the Houston and Dallas courts would be evenly distributed over three election cycles.

In 1979, the Legislature passed a resolution to ask the voters of Texas to vest the intermediate appellate courts with criminal jurisdiction.[185] The voters approved the constitutional amendment in 1980, and the Legislature implemented it in 1981.[186] But in addition to giving the intermediate appellate courts criminal jurisdiction, the Constitution also was amended to delete the provision regarding drawing for classes on the appellate courts. The Legislature added twenty-five justices to the courts effective in September 1981, and added three additional justices to the Austin court effective in September 1982.[187]

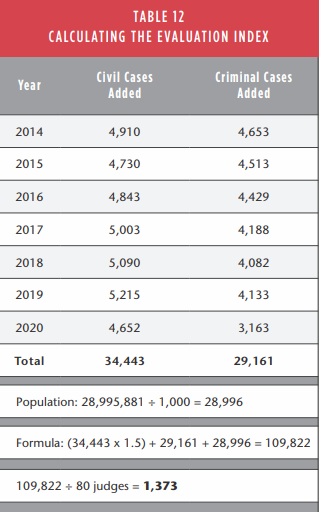

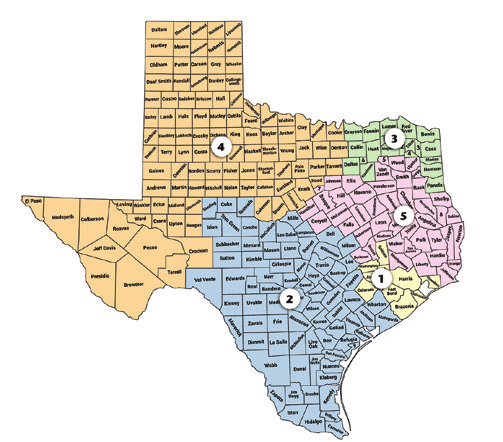

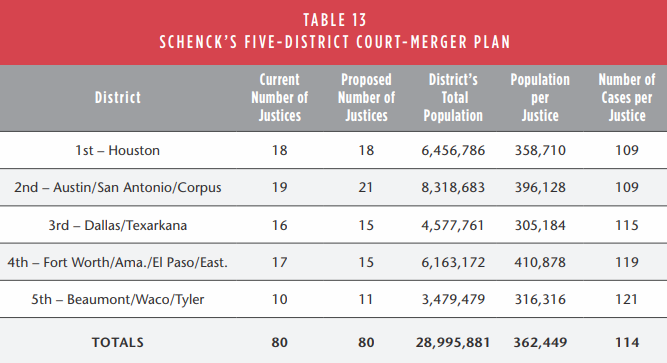

Two justices elected in November 1982 to new positions on the First and Fourteenth Courts of Appeals in Houston were informed that lots would be drawn to determine whether their terms of office would be for two, four, or six years, as required by law. [188] They filed a lawsuit seeking a writ of mandamus preventing the drawing of lots for positions on the courts, arguing that the statute was in conflict with the new version of Article V, section 6 of the Constitution, providing that justices on the courts of appeals be elected for six-year terms.[189] The Texas Supreme Court agreed.[190] Thus, all of the justices elected in 1982 to fill newly created positions served six-year terms. As a result, forty-five of the eighty intermediate appellate court justices in Texas are elected in the same election cycle (election years 2018, 2024, etc.), while nineteen are elected in the next cycle (2020, 2026, etc.), and sixteen are elected in the third cycle (2022, 2028, etc.), as shown in Table 10. In contrast, if election of the justices were evenly distributed, twenty-six or twenty-seven justices would be elected in each election cycle.